By Erin Spinney

Introduction

With the growing demands of the repeated global imperial wars of the long eighteenth century, on shore provision of British naval medicine became centralised in two large clinical hospitals.[1] The first of these institutions, Haslar Naval Hospital in Portsmouth, first received patients while it was still under construction in 1753. The building would eventually finish construction in 1762, the same time that the second institution, Plymouth Naval Hospital in Plymouth, also opened.[2] These new centralized facilities changed the delivery of naval medicine, with patient numbers as high as 2000 at Haslar during times of war; the institution therefore required a large workforce of care givers to function.[3] Naval medical officers in charge of these institutions like James Lind, physician at Haslar from 1753-1783, and others have frequently featured in histories of naval medicine.[4] Yet, while the medical care provided by these medical officers was important, the success of their work relied upon hundreds of servants to the hospital including nurses, washerwomen, seamstresses, labourers, and others who provided or facilitated the provision of day-to-day care.[5] By the time of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in the late eighteenth century, these workers and the institutions they laboured for were intrinsically part of the wider fiscal-military state.[6]

To ensure order and regularity among such a large workforce, particularly one of dual naval and civilian character, instructions were issued regularly by the Admiralty and Sick and Hurt Board for medical officers such as physicians, surgeons, and hospital administrators including stewards, agents, and from 1795 hospital governors. The regulations for sick pay and provision of medical care for nurses at British naval hospitals changed little from their introduction in 1763 and their printed publication in the 1808, Instructions for the Royal Naval Hospitals at Haslar & Plymouth.[7] Similarly, the pages of naval hospital pay lists recorded at monthly intervals, are littered with recordings of sick days, half pay, and notations of nurses discharged dead from their service.[8] Yet, while pay list records document the quantitative details of sick pay and sick time administration and regulations codify what should be provided, these documents do not describe what injuries and illnesses befell nurses at British naval hospitals.

This article seeks to better understand the experiences of sick and injured nurses and the lengths to which the state would go to facilitate their cure, care, and return to duty. To do so I rely on the only surviving register of sick nurses at Haslar Naval Hospital which covers the two-year period from January 1814-December 1815.[9] A statistical analysis of the most common illnesses and injuries will be performed. This analysis will then be cross-referenced with Haslar pay list records for the same period to determine when and for what conditions naval hospital administrators and the Sick and Hurt Board were willing to keep nurses in the sick ward beyond the 28-day provision of the regulations. I argue that the care provided for sick and injured nurses demonstrates the enduring commitment of the fiscal-naval state to provide for its people in wartime settings.

Historiography and Methods

Nurses, their physical welfare, and treatment that they received while sick have been considered by historians as either an issue of occupational health or to showcase the effects of extreme nursing circumstances as in the First and Second World War. Deborah Palmer’s Who Cared for the Carers?investigates how the choices made by nurse and hospital management contributed to nurses’ experiences of ill health and professional identity between the rise of professional nursing and the establishment of the National Health Service.[10] Nurses were employees first and foremost, whatever the public perception of nurses and nursing as a selfless, suffering, vocation.[11] The intersection of vocation, necessity, and gendered sensibilities, is also present in First World War historiography for British and Canadian nurses.[12]

Yet, the eighteenth and early nineteenth century nurses who worked in British naval hospitals were different from professional nurses in the twentieth century. As my previous work has shown, nurses in these long-eighteenth century naval institutions occupied a position in a ‘hospital household,’ more akin to the employment status of domestic servants at large English households.[13] Nurses in these institutions were also cared for in ways similar to domestic servants while they were employed at the hospital.[14] They were not allowed to contract for their own medical care, which was to be supplied by their employer – the state.[15] Thus, while it is useful to consider the treatment that sick nurses received in naval hospitals as an aspect of occupational health, naval hospitals had the same duty to care for their nurses as any other servant.

Medical care provided to nurses and other servants of the hospital was also part of a wider humanitarian framework of military and naval medicine. Describing the work of British army nurses in the Second World War, Jane Brooks states ‘Nurses were therefore important to maintaining humanity not only in the hospital wards, but also in the wider community.’[16] By extending care to nurses in British naval hospitals, the state could express its enduring commitment to medical treatment for its people. Perceptions of humanity and the ability for sick and injured to receive medical care when needed was part of a recruitment strategy for eighteenth century military forces.[17]

The role of humanity and eighteenth-century conceptions of military masculine duty also played a role in medical care provided for women at naval hospitals. Extreme circumstances, such as the explosion of the HMS Amphion, could also cause sick and injured women to enter the hospital. Governor Richard Creyke recorded how on 6 September 1796, ‘A woman being brought to the Hosp. much hurt by the blowing up of the Amphion was from motives of humanity received and sent into a ward by the Asst. Surgn. attending at the receiving room, and from the same motive directed by me to be entered as a Nurse and sent into the Sick Nurses ward’.[18] Pay lists show her to be Jane Stockdale, who remained in the hospital as a nurse in name only for six weeks, until 20 October.[19] There is no indication in Creyke’s Memoranda Book of him informing the Admiralty or the Sick and Hurt Board of Stockdale’s admittance. Nor is there any mention of the incident in the surviving records. The motives of humanity mentioned above may have kept him from doing anything, such as informing those above him in the chain of command, which might have jeopardised Stockdale’s recovery by causing her to be removed from the hospital.[20]

Sick Ward and Sick Pay Regulations During the Long Eighteenth Century

As mentioned above, there were formalised regulations which described the care that sick and injured nurses of either Haslar or Plymouth naval hospital could receive. The earliest from May 3, 1763, seem to codify at Plymouth a manner of taking care of sick nurses that was already being practiced at Haslar:

Having taken into consideration your Letter of the 2nd of July last respecting the Nurses at Haslar Hospital and have come to the resolution that for the future all Sick Nurses shall be treated in every respect as the other Patients and be allowed Half Pay for twenty eight days after they are taken Ill. If they continue so long sick and If at that time it shall appear that the disorder may be curable in a short time they are to be continued there but are not to be allowed Pay till their recovery is perfected but If after the expiration of the Month it shall appear the Nurse still continued to be Ill and not likely soon to recover the same is to be respected to the Physicians and Council to whom We have wrote on this subject and such Nurse to be by them discharged as Unserviceable.[21]

The twenty-eight day provision listed here, as the time that sick nurses were allowed to continue to receive half pay in hospital was the same limit that was set for sick seamen on shore in a 7 August 1746 order.[22] This 1746 order from the Sick and Hurt Board was a response to observations that “many of the Men set Sick on Shore from His Majesty’s Ships or Vessels for Cure, are kept often some Months in the Hospital or Quarters, and probably much longer than necessary, which must be attended with great and needly Expence to the Crown.”[23] The issue here, as with the 1763 regulation concerning nurses received in hospital, was both the cost of care and the need for these sick individuals to be returned to duty as soon as medically possible.

A variation on this instruction for care for sick nurses persisted for the rest of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century. Medical treatment was extended to other servants of the hospital (explicitly washerwomen and labourers) in an October 1772 Instruction book to the Agents at naval hospitals. Agents were to keep a ‘Cheque Book’ to record the names of hospital personnel who were not to be paid either due to ‘neglect of duty or misbehaviour’, or ‘if any Nurse Washerwoman, or Laborer continues Sick and unable to do their duty for more than 28 Days successively’.[24] The 1772 instructions given to naval hospital Stewards also carried the same twenty-eight day provision.[25]

Instructions for Hospital Governors issued in 1797, changed the time frame that sick servants were to be kept as patients on half pay to thirty days, after which point the Governor was ‘to inform the Commissioners for Sick and Wounded Seamen thereof and of the probable time that will be requisite for the Persons recovery that the Commissioners may determine what shall be necessary to be done on that occasion’.[26] Although this is the only instance of the thirty day time period being described in regulations, thirty days was more a reflection of what occurred in the pay list records than twenty-eight days. Pay list records for both Haslar and Plymouth naval hospital contain the notation ‘No pay ill above a month’.[27] Whether the time limit was twenty-eight or thirty days, the time a nurse or other hospital servant could spend in hospital receiving care on half pay was extensive.

Medical treatment was officially extended to all servants of the hospital in the printed Instructions for the Royal Naval Hospitals at Haslar & Plymouth published in 1808:

When sickness or hurts shall prevent any of the Labourers, Nurses, Washerwomen, or other Servants of the Hospital, from performing their duty, they are to be received into the wards as Patients, and check of half their pay, during the time they may continue sick, provided the same shall not exceed thirty days, but such as remain sick beyond that time are to be checked of their whole pay, while they may afterwards continue so; and you are to cause proper information to be given to the Commissioners [of the Sick and Hurt] of the probably time that they will still be required for their recovery, in order that they may determine what may be necessary to be done on the occasion.[28]

As can be seen successively in the 1763, 1772, 1797 and 1808 instructions, the primary concern of naval regulators was who was eligible for sick care, for how long they were eligible, and how much pay they should receive and when. In none of these instructions, nor in the variations of these instructions that were issued in the second half of the eighteenth century, was there any stipulation of what type of care could be received by sick and injured nurses.

The cases of two nurses, Jane Nicoloi and Mary Pierce, and one washerwoman Ann Burk demonstrate that surgical care was sometimes provided to those who needed it. Both Nicoloi and Pearce had an arm amputated and Ann Burk a leg amputated by Haslar surgeon Robert Dodds in the spring of 1778. In the pay list records their listing as sick starts on 7 February 1778 for Pearce, 27 May 1778 for Nicholoi, and April 27 1778, for Burk.[29] A letter from the Haslar Physician and Council to the Sick and Hurt Board on 7 September 1778 makes mention that nurses Pearce and Nicoloi and washer woman Burk ‘will be soon well’.[30] There was a follow up letter from Physician and Council to the Sick and Hurt Board on 16 October 1778. This letter provided details on the nurses injury ‘Ulcers on their Hands from a Taint received in Wringing the Fomentation Cloths that had been applied to Carious and putrid Ulcers of Patients in their Wards’.[31] It also states why Haslar’s physician and council was recommending that both nurses be discharged: ‘We are of Opinion that as these Women had the Misfortune to lose their hands they cannot act as Nurses in any Sick Ward not being able to raise up a Patient in his Bed, to make his Bed or properly to Attend the receipts of Provisions and Stores’.[32] As the letter makes clear the Physician and Council did not believe that Pearce and Nicoloi would be able to handle their basic duties of nursing care, feeding, and maintaining cleanliness in the environment of a sick ward.[33] However, both Pearce and Nicoloi, with the support of Robert Dodds petitioned the Sick and Hurt Board to remain as nurses. Dodds believed that they might be able to work capably and well in an ‘Itchy Ward’.[34] In their petition only Nicoloi was successful and it is unclear why. She had only been working at the hospital since 5 April 1778 while Pearce had been employed since 30 October 1777.[35] Normally seniority of nurses helped their petition. Nicoloi would continue working at the hospital receiving half pay of £6 per year, presumably being seen by administrators as only being able to perform half her work.[36] Yet, the cases of Pearce, Nicoloi, and Burk all show the extent to which the hospital was willing to provide complex care for its own even during wartime.

Different sources describe medical ailments and treatments that nurses received in hospital. For example, the minutes of Haslar’s physician and council occasionally describe sick nurses as in the cases of Sarah Button with her swollen hand and Elizabeth Francis with an ulcer on her leg.[37] Aside from mentions of when nurses returned to duty, especially if they were off sick for a prolonged period, however, it is rare for these minute books to describe what a nurse was sick with. Similarly, letters from both the Physician and Council and after the appointment of a hospital governor in 1795, letters from Haslar Governor William Yeo contain reports of nurses who remained in hospital past the allotted half-pay time. Sarah Walker was hospitalised in November 1800 with an ulcer, when it was reported by Doctor Hope that ‘the time of her recovery uncertain’.[38] Elizabeth Kimber another nurse with a ‘recovery uncertain’ according to surgeon, Mr. Fitzmaurice, was also reported by Governor Yeo to the Sick and Hurt Board on 29 October 1802.[39]

Sick Servants’ Muster 1814-1815

The only surviving distinct record of the illness or hurt that nurses were treated for is the muster book for sick servants kept from January 1814 to December 1815.[40] There are no musters for May 1814 suggesting that there were no sick servants at this time. This has been corroborated with the pay list records for 1814.[41] Like the number of patients in the hospital the number of patients in the sick nurses’ ward fluctuated. September 1815 was month with the most patients mustered in the sick ward.[42] These muster sheets, known as ‘muster sheet number 38’ were required to be kept as per the 1808 instructions.[43] It is quite possible that muster books for other years at one time existed but have since been lost. Within the muster records there are thirty eight women (thirty one nurses, six washerwomen, and one scrubber) and six men (five labourers and one hospital mate) who received treatment.[44] Nurses made up the largest proportion of women labourers at Haslar so it is unsurprising that they would also make up a higher proportion of care in the sick ward.

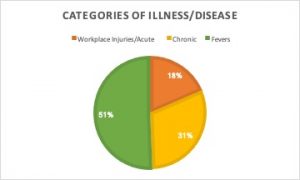

Yet these numbers show that nurses received the most care of any class of servant, which suggests either they were at a greater risk for injury or more apt to require medical treatment due to their age. ‘Age and infirmity’ was often used by hospital administrators to petition the Navy’s Sick and Hurt Board for pensions for nurses. On 22 October 1795, the Admiralty endorsed the half pay superannuation request of Plymouth Naval Hospital’s Physician and Council for nurses Honor Palmer and Margaret Rogers.[45] Generosity was recommended due to the ‘long and faithful Services’ of nurses Palmer and Rogers ‘who from Old Age and Infirmities are no longer capable of Service’.[46] Of the women listed in the sick muster their reasons for treatment can be divided into three categories, workplace injuries and acute infections, chronic injuries or diseases, and fevers. I will consider each of these categories in turn.

[Figure 1] Categories of Illness/Disease for all Sick Servants.[47]

Workplace Injuries and Acute Infections

Workplace injuries and acute infections are the easiest to identify. These aliments often resulted in hospital stays of less than a month. The injuries can also be clearly tied to the workplace as in the case of nurse Mary Bittle who was admitted into the sick ward with a scalded foot on 7 October 1814 and discharged to duty on 26 October.[48] Washer woman Mary Gauntlett and her contused side can similarly be tied to her duties as a washer on the Russian service. Gauntlett was admitted to hospital on 21 March 1814 and discharged to duty on 27 March.[49]

Other acute injuries and illnesses are harder to tie directly to the women’s labour in the hospital. Washer woman Sarah Thomas was admitted to hospital on 26 June 1814 with a diagnosis of measles and was discharged to duty on 4 July.[50] Unlike nurses, washer women did not live in the hospital, so it is possible that Thomas contracted her illness outside the institution.

Several individuals were admitted into hospital for inflammation plaguing some part of their body. This included Nurse Mary George admitted to the hospital 28 January 1814 and discharged 30 March 1814. Her diagnosis reads ‘Same hand & Dysentery’, suggesting that she had been admitted into the hospital for previous inflammation of her hand which would have been recorded in muster books which have since been lost.[51] Nurse Sarah Graystock was hospitalised for 54 days from 10 November 1814 to 3 January 1815 for her inflamed hand. While both nurses Elizabeth Elliot for her inflamed leg from 22-31 December 1814 and Mary Hooley from 26 November to 1 December 1814 for inflammation of the bowels had shorter stays in hospital.[52]

The final subcategory of acute illness was respiratory. Washerwoman Sarah Marshall was hospitalized in March 1814 for a cough, while nurses Dinah Brooks, Mary McDonald, and Sarah Atkins, and a washerwoman also named Mary McDonald were all admitted for pneumonia. Of these, all but Brooks hospitalised in September 1815 would remain in hospital until discharged to duty in October.[53]

Chronic Illnesses or Diseases

Chronic conditions could also be subcategorised into those dealing with chronic pain rheumatism, respiratory complaints, and ulcers or other skin conditions. Rheumatism like fevers, impacted all types of servants listed on the muster record (except the hospital mate), but particularly effected washer women and nurses. Isabella Wells and Patience Case, both washer women, were hospitalized for a little over two weeks for rheumatism in October and November 1814 respectively. Both were discharged to duty after their stay in hospital. Similarly nurses Dinah Brooks and Elizabeth South were also in hospital for rheumatism. Brooks had been hospitalised for pneumonia before she was in hospital for over a month between 6 March 1814 and 4 April 1814. In both instances she was discharged to duty. While South was also eventually discharged to duty, her hospitalisation was much longer from 18 January to 8 April 1815.[54]

Other chronic conditions include the gout of nurse Mary Murphy and the various conditions of Catherine Brean. Murphy was hospitalised twice for her gout, the first time between 15 March and 31 March 1814. Her second stay in hospital was longer from 5 October to 15 November 1814. In both cases she was discharged to duty. Brean was first hospitalised by pneumonia between the 3-10 April 1815 while she was working as a nurse. She was back under medical care, this time with a fever, nine days later, on 19 April 1815. Her job description is now listed as ‘scrubber’ instead of nurse.[55] However, this change in designation does not appear in the pay list records where she is always listed as a scrubber.[56] It is possible that her job title was miscategorised on the muster of sick servants and shows the difficulty of consulting only one document. Brean would again be hospitalised for pneumonia from 27 September to 4 October 1815 and was again discharged to duty. Because the sick servants muster ends in December 1815 it is not possible to determine whether Brean or Murphy were hospitalised further for their conditions.[57]

Like Brean, nurse Elizabeth Harrington also suffered respiratory complaints. Harrington was in hospital for phthisis from 17 March to 5 April 1814. Phthisis was a diagnosis of a wasting disease with symptoms of consumption or as we would now classify it tuberculosis.[58]

The final category of chronic conditions, skin conditions, included nurse Mary Watley with her ulcerated foot, and nurse Ann Cline with her ulcer. Cline was in hospital for two weeks from 1-14 February 1815 before she was discharged to duty. Watley was hospitalised for two separate periods. The first from 1 October to 17 November 1814 was for the ulcerated foot. After this hospitalisation she was discharged to duty. She was back in the sick nurses’ ward from 23 January to 27 February 1815. In this case her ailment is just listed as ‘ulcer’ the location of which is not specified. Again, she was discharged to duty after this course of treatment.[59]

Fevers

The final category of sickness that appears in the muster for sick servants was fevers. Fevers effected eighteen people with various job descriptions, including the case of Catherine Brean discussed earlier. Of these four were laborers, one was a scrubber, two were washer women, and eleven were nurses. Of these the case of nurse Mary Boyns is illustrative of long-term care for hospital staff in naval hospitals. Boyns was first hospitalised on 19 April 1815 and there she would remain until at least 31 December 1815 when the sick servants muster ends.[60] Pay list records show that hospital administrators followed sick pay regulations: she did not receive any half pay after May 1815, but she remained in the hospital under treatment.[61] We can follow her sickness in the pay list records for 1816 where she is listed as sick for all of January and February, until she was discharged dead on 28 February 1816.[62] Boyns was under treatment for almost a year. It is impossible to know why she was kept under treatment for so long especially as her case clearly did not show any improvement according to the sick servants musters or her continued sickness into 1816 and her ultimate death. The pay list records also show nothing remarkable about Boyns’ seniority as a nurse where she is roughly in the middle of the list of nurses.[63] What Boyns’ continued care does demonstrate however, is that even chronic cases among the nurses could be and were sometimes met with indulgence by medical officers and hospital administrators.

The vast majority of servants admitted to hospital were discharged to return to duty. There were four kinds of exceptions as seen in the experiences of six individuals. The fate of Hospital Mate Hughes was to be left in the hands of the Sick and Hurt Board when he was discharged on 3 October 1815. One labourer, John Morris chose to leave the hospital at his own request after his short stay in hospital for a fever from 28 June to 4 July 1814.[64] Three nurses, Elizabeth Elliott (hospitalised a second time, for fever), Mary Banton, represented in the muster and the pay list records as Mary Banton (2), and Mary Townsend had their discharged categorised as part of a ‘reduction’.[65] A reduction, also known as a force reduction, was designed to keep the number of nurses and patients in alignment according to the naval regulations of one nurse for every seven patients.[66] All the reductions occurred in October or November 1815.[67] Banton was also recorded as having a fever, while Townsend was listed with an ‘Absscess’ [sic].[68] When comparing these nurses’ seniority on the pay list records for October and November all were relatively junior.[69] The timing also coincided with a general decrease in naval operations following the end of the Napoleonic Wars and a return to a peace time establishment. The final exception was nurse Elizabeth Whitewood who was admitted to hospital for debility on 21 January 1815, she was discharged from the hospital just three days later and was listed as superannuated.[70] These nurses would remain in the hospital during their retirement and would continue to receive food, accommodation, and half pay for the remainder of their lives.[71]

Going Beyond Provisions in Regulations

In assessing the lengths that the state would go to provide care for nurses it is important to consider how often hospital administrators went beyond the twenty-eight-day provision for medical care outlined in the regulations. Table 1 lists all the nurses who were kept in hospital for less than twenty-eight days sorted according to length of stay.

[Table 1] Sick nurses cared for in hospital for less than 28 days.[72]

| Surname | Forename | Condition |

Days in Hospital |

| Bittle | Mary | Scalded foot | 20 |

| Harrington | Elizabeth | Phthisis | 20 |

| Thomas | Sarah | Fever | 20 |

| Atkins | Sarah | Pneumonia | 19 |

| MacDonald | Mary | Pneumonia | 19 |

| Blair | Catherine | Continued | 18 |

| Elliott | Elizabeth | Fever | 17 |

| Murphy | Mary | Gout | 17 |

| Harley | Mary | Fever | 16 |

| Cline | Ann | Ulcer | 14 |

| Ross | Ann | Fever | 14 |

| Wood | Ann | Fever | 14 |

| Harley | Mary | Ulcer | 13 |

| Robinson | Lydia | Fever | 13 |

| Jones | Hannah | Enteritis | 11 |

| McLean | Sarah | [Unknown] | 10 |

| Banton (2) | Mary | Fever | 9 |

| Light | Mary | Fever | 9 |

| Brooks | Dinah | Pneumonia | 8 |

| Hodges | Ann | Fever | 8 |

| Francis | Mary | Fever | 6 |

| Hooley | Mary | Inflammation of Bowles | 6 |

| Whitewood | Elizabeth | Debility | 3 |

The twenty-three nurses represented in this table represent 66 percent of the total number of nurses cared for during the period of the hospital musters. Sorting the table by the length of stay also demonstrates that most nurses were kept in hospital for more than a week after their admission. Only the clearest of diagnoses, that of Elizabeth Whitewood’s debility were discharged quickly from the hospital. I argue that this demonstrates a commitment to care for the nurses of Haslar naval hospital even within the confines of the twenty-eight-day limit of hospital administrators’ authority. Nurses deemed sick enough to enter into the sick nurses’ ward as patients were not rushed through treatment so that they could resume their duties.

The degree to which the hospital went to care for its own was even more clearly demonstrated in the case of the 34 percent of nurses who were kept in hospital beyond the twenty-eight-day provision in regulations.

[Table 2] Sick Nurses Cared for in Hospital for More Than 28 days.[73]

| Surname | Forename | Condition | Days in Hospital |

| Boyns | Mary | Fever | 257 |

| Elliott | Elizabeth | Fever | 90 |

| South | Elizabeth | Rheumatism | 81 |

| McCoy | Ann | Fever | 63 |

| George | Mary | Same hand & Dysentery | 62 |

| Graystock | Sarah | Inflamed Hand | 55 |

| Watley | Mary | Ulcerated Foot | 48 |

| Townsend | Mary | Abscess | 44 |

| Murphy | Mary | Gout | 42 |

| Ferris | Elizabeth | Fever | 37 |

| Watley | Mary | Ulcer | 36 |

| Brooks | Dinah | Rheumatism | 30 |

Even if Boyns’ extraordinary long stay in hospital is removed, Table two shows that nurses were regularly cared for in hospital for two months or more. While at this time the nurses would not receive half pay during their treatment, the hospital was still providing them with all the benefits of patients including treatments, diet, and hospital dress.

Conclusion

Nurses and other workers classed as hospital servants were a valued part of the naval medical system and the care and cure that they received at British naval hospitals often went beyond the confines of the official regulations. The cases shown in the 1814-1815 muster book for Sick Servants help us to understand what brought these men and women to receive treatment and supplement what can be gleaned from pay list records alone. Integrating their experiences into the story of naval medicine can help us as historians better understand naval hospitals as workplaces. The care work provided by nurses in these institutions was in turn extended to them by the naval medical system when the carers became recipients of care. Meanwhile, an examination of the type of ailments treated in the sick servants’ muster shows how diseases and illnesses among hospital staff were a combination of acute (likely hospital-acquired infections) and chronic conditions exacerbated by the age of the workforce and the difficulty of the labour.

This research suggests, too, that nurses were not merely replaced: they had acquired skills worth retaining, and therefore were accorded a higher status by their employers than we have been led to expect in this period.

Endnotes

[1] This centralisation did not mean that previous models of contract hospitals were completely cast aside by the navy’s Sick and Hurt Board. For more on the operation of these contract institutions see Matthew Neufeld, ‘Neither private contractors nor productive partners: The English fiscal-naval state and London hospitals, 1660-1715’, International Journal of Maritime History 28/2 (2016), 268-290; Matthew Neufeld and Blaine Wickham, ‘The State, the People and the Care of Sick and Injured Sailors in Late Stuart England’, Social History of Medicine 28/1 (2015).: 45-63; Patricia Crimmin, ‘British Naval Health, 1700-1800: Improvement over Time?’, in British Military and Naval Medicine, 1600-1830, ed. by Geoffrey Hudson (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007), 184-186.

[2] Christine Stevenson, Medicine and Magnificence: British Hospital and Asylum Architecture, 1660-1815 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000), 182; Margarette Lincoln, ‘The Medical Profession and Representation of the Navy, 1750-1815’, in British Military and Naval Medicine, 1600–1830, ed. by Geoffrey Hudson (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007), 210.

[3] Christopher Lloyd and Jack Coulter, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900, Volume III 1714-1815 (Edinburgh and London: E & S Livingstone, 1961), 213.

[4] David Harvie, Limeys: The True Story of One Man’s War Against Ignorance, the Establishment, and the Deadly Scurvy (Stroud: Sutton, 2002); Iain Milne, ‘Who was James Lind, and what exactly did he achieve’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 105/12, 503-508; Laurence Brockliss, John Cardwell, and Michael Moss, Nelson’s Surgeon: William Beatty, Naval Medicine, and the Battle of Trafalgar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[5] Erin Spinney, ‘Servants to the Hospital and the State: Nurses in Plymouth and Haslar Naval Hospitals, 1775-1815’, Journal for Maritime Research 20/1-2 (2018), 3-19; Erin Spinney, ‘Naval and Military Nursing in the British Empire c. 1763-1830’, (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 2018); Erin Spinney, ‘The Women of Haslar and Plymouth: Washerwomen, Nurses, and the Work of Creating a Healing Medical Environment’, in Military Health Care and the Early Modern State, 1660-1830: Management – Professionalisation – Shortcomings, eds. Sabine Jesner and Matthew Neufeld (Graz: V&R Unipress, 2023), 72-85 (in press).

[6] Roger Knight, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory, 1793-1815 (London: Penguin Books, 2013).

[7] Instructions, precedents, and historical notes relating to the Sick and Hurt Board, collected for the Board of Revisions: Vol 1, 1805, The National Archives (hereafter TNA), ADM 98/105; Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[8] Haslar: pay lists, 1813-1814, TNA, ADM 102/393; Haslar: pay lists, 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[9] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[10] Deborah Palmer, Who Cared for the Carers?: A History of the Occupational Health of Nurses, 1880-1948 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 1, 3.

[11] Palmer, Who Cared for the Carers?, 15.

[12] Ariane Gauthier, ‘“Long and Strenuous Duties in France”: Neurasthenia and Nervous Debility among Canadian Nursing Sisters during the First World War’, Canadian Military History 31/1 (2022), 1-29.

[13] Erin Spinney, ‘Servants to the Hospital and the State’, 5.

[14] John Woodward, To Do the Sick No Harm: A Study of the British Voluntary Hospital System to 1875 (London: Routledge, 1978), 40-41; Michael James, ‘Health care in the Georgian household of Sir William and Lady Hannah East’, Historical Research 82/2 (2009), 697.

[15] Catherine Crawford, ‘Patients’ Rights and the Law of Contract in Eighteenth-Century England’, Society for the Social History of Medicine 13/3 (2000), 382.

[16] Jane Brooks, Negotiating Nursing: British Army Sisters and Soldiers in the Second World War (Manchester: University of Manchester Press,2018), 106.

[17] Lincoln, ‘The Medical Profession and Representations of the Navy’, 203.

[18] Private minute and memoranda book kept by Captain Richard Creyke, Governor of the Royal Hospital at Plymouth, covering the period 1795-1799. Typed transcript from Captain T.P. Gillespie, National Maritime Museum (hereafter NMM), TRN/3, 54.

[19] Plymouth: pay lists, 1794-1797, TNA, ADM 102/688.

[20] For more motives of humanity in caring for servicemen during war see Erica Charters, Disease, War, and the Imperial State: The Welfare of the British Armed Forces during the Seven Years’ War (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2014) and civilians see Erica Charters, Eve Rosenhaft and Hannah Smith, ‘Introduction’, in Civilians and War in Europe 1618-1815, Erica Charters et al eds. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012), 4-5.

[21] ‘General Orders to the Steward’ in Instructions, precedents, and historical notes relating to the Sick and Hurt Board, collected for the Board of Revisions: Vol 1, 1805, TNA, ADM 98/105, 250.

[22] Instructions and Precedents, TNA, ADM 98/105, 15-16.

[23] Instructions and Precedents, TNA, ADM 98/105, 15.

[24] Instructions and Precedents, TNA, ADM 98/105, 186.

[25] Instructions and Precedents, TNA, ADM 98/105, 259.

[26] Instructions and Precedents, TNA, ADM 98/105, 457.

[27] Plymouth: pay lists, 1777-1779, TNA, ADM 102/683; Plymouth: pay lists, 1780-1781, TNA, ADM 102/684; Plymouth: pay lists, 1782-1784, TNA, ADM 102/685; Plymouth: pay lists, 1784-1788, TNA, ADM 102/686; Plymouth: pay lists, 1789-1794, TNA, ADM 102/687; TNA, ADM 102/688; Plymouth: pay lists, 1798-1799, TNA, ADM 102/689; Haslar (Pay Lists) 1769-1772, TNA, ADM 102/375; Haslar (Pay Lists) 1773-1776, TNA, ADM 102/376; Haslar (Pay Lists) 1777-1778, TNA, ADM 102/377; Haslar (Pay Lists) 1779-1780, TNA, ADM 102/378; Haslar: Pay Lists, 1780-1781, TNA, ADM 102/379; Haslar: pay lists, 1782-1783, TNA, ADM 102/380; Haslar: pay lists, 1783-1786, TNA, ADM 102/381; Haslar: pay lists, 1787-1790, TNA, ADM 102/382; Haslar: pay lists, 1790-1793, TNA, ADM 102/383; Haslar: pay lists, 1794-1795, TNA, ADM 102/384; Haslar: pay lists, 1795-1796, TNA, ADM 102/385; Haslar: pay lists, 1796-1797, TNA, ADM 102/386; Haslar: pay lists, 1798-1799, TNA, ADM 102/387; Haslar: pay lists, 1800-1802, TNA, ADM 102/388; Haslar: pay lists, 1802-1805, TNA, ADM 102/389; Haslar: pay lists, 1806-1808, TNA, ADM 102/390; Haslar: pay lists, 1809-1810, TNA, ADM 102/391; Haslar: pay lists, 1811-1812, TNA, ADM 102/392; Haslar: pay lists, 1813-1814, TNA, ADM 102/393; Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[28] Instructions for the Royal Naval Hospitals at Haslar & Plymouth (St. George’s Field: The Philanthropic Society, 1808), 12-13.

[29] Haslar (Pay Lists) 1777-1778, TNA, ADM 102/377.

[30] Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar, Council out-letter books, 1778-1790, TNA, ADM 305/15.

[31] Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar, Council out-letter books, 1778-1790, TNA, ADM 305/15.

[32] Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar, Council out-letter books, 1778-1790, TNA, ADM 305/15.

[33] Philip Stephens to Commissioners of the Sick and Hurt Board, Enclosure 29 September 1778, Sick and Hurt Board, In-Letters and Orders, Jan 1, 1775-Dec 31, 1780, NMM, ADM/E/42.

[34] Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar, Council out-letter books, 1778-1790, TNA, ADM 305/15; Roberts Dodds to Sick and Hurt Board, 2 October 1778, NMM, ADM/E/42.

[35] Haslar (Pay Lists) 1777-1778, TNA, ADM 102/377.

[36] Haslar (Pay Lists) 1777-1778, TNA, ADM 102/377; Haslar (Pay Lists) 1779-1780, TNA, ADM 102/378.

[37] Physician and Council to Sick and Hurt Board, April 6, 1777, TNA, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar Council Out-Letter Books, ADM 305/14.

[38] William Yeo to Commissioners for Sick and Hurt, 5 December 1800, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar, Governor’s out-letter books, TNA, ADM 305/25.

[39] William Yeo to Commissioners for Sick and Hurt, 29 October 1802, Royal Naval Hospital, Haslar, Governor’s out-letter books, TNA, ADM 305/28.

[40] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[41] Haslar: pay lists, 1813-1814, TNA, ADM 102/393.

[42] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[43] Instructions for the Royal Naval Hospitals at Haslar and Plymouth, Appendix no. 38.

[44] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[45] Evan Nepean to Sick and Hurt Board, October 22, 1795, Sick and Hurt Board, In-Letters and Orders, 1794-1796, NMM, ADM/E/45.

[46] Evan Nepean to Sick and Hurt Board, October 22, 1795, NMM, ADM/E/45.

[47] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[48] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[49] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[50] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[51] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[52] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[53] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350; Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[54] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[55] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[56] Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[57] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[58] Thomas Reid, An Essay on the Nature and Cure of the Phthisis Pulmonalis (London: T. Cadell, 1782), v-viii.

[59] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350; Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[60] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[61] Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[62] Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[63] Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394. For the importance of seniority in naval hospital pay list records see Spinney, ‘Naval and Military Nursing in the British Empire’, 220-225.

[64] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350; Haslar: pay lists, 1813-1814, TNA, ADM 102/393.

[65] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[66] Instructions for the Royal Naval Hospitals at Haslar and Plymouth, 10.

[67] Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[68] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[69] Haslar: pay lists, 1815-1816, TNA, ADM 102/394.

[70] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[71] Instructions and precedents, 15 December 1803, TNA, ADM 98/105, 476-477.

[72] Haslar (Sick Servants, 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.

[73] Haslar (Sick Servants), 1814-1815, TNA, ADM 102/350.