| Sarah Rogers, University of Huddersfield | The UKAHN Bulletin |

| Volume 8 (1) 2020 | |

Eva Lückes (1854-1919) was appointed as matron of the prestigious London Hospital in 1880, at the relatively young age of 26. Historians have previously portrayed her as a determined, single-minded disciplinarian who did not falter in her opposition to nurse registration over her thirty-nine-year tenure at The London.1

Eva’s letters to her friends Florence Nightingale and Margaret Paul enable a more in-depth analysis of her personality and characteristics over a thirty-year period.2 Whilst the letters support the historiography, they also reveal a more human and softer side. The correspondence shows her ‘firmness of purpose’ and determination to maintain her position about current issues in nursing, but also exposes a sensitive and vulnerable person who took the personal animosity to heart.3 In these letters Eva describes her love of the sea, to which she often retreated for recuperation, refreshment, relaxation and solace throughout her long and challenging career.

In January 1891 Eva made the long, and probably, uncomfortable journey to the Isles of Scilly, a group of islands situated off the southwestern tip of England.4 Their warm climate and tranquil life style have, since the mid-nineteenth century, made them an attractive escape from the hustle and bustle of the mainland. Eva was escaping from the deadly air pollution, fog and poverty of the East End of London during a particularly turgid time in her long career as matron of the hospital. In the previous summer of 1890, she had been interviewed for three days during the House of Lords Select Committee enquiry into Metropolitan Hospitals, which ran from May 1890 until July 1891.5 Lückes’s explanations regarding her management of the nursing department, of what was the largest hospital in England, were critically examined both by the enquiry panel, the press and by fellow professionals, including her highly vociferous and constant ‘opponent’ Mrs Ethel Fenwick.

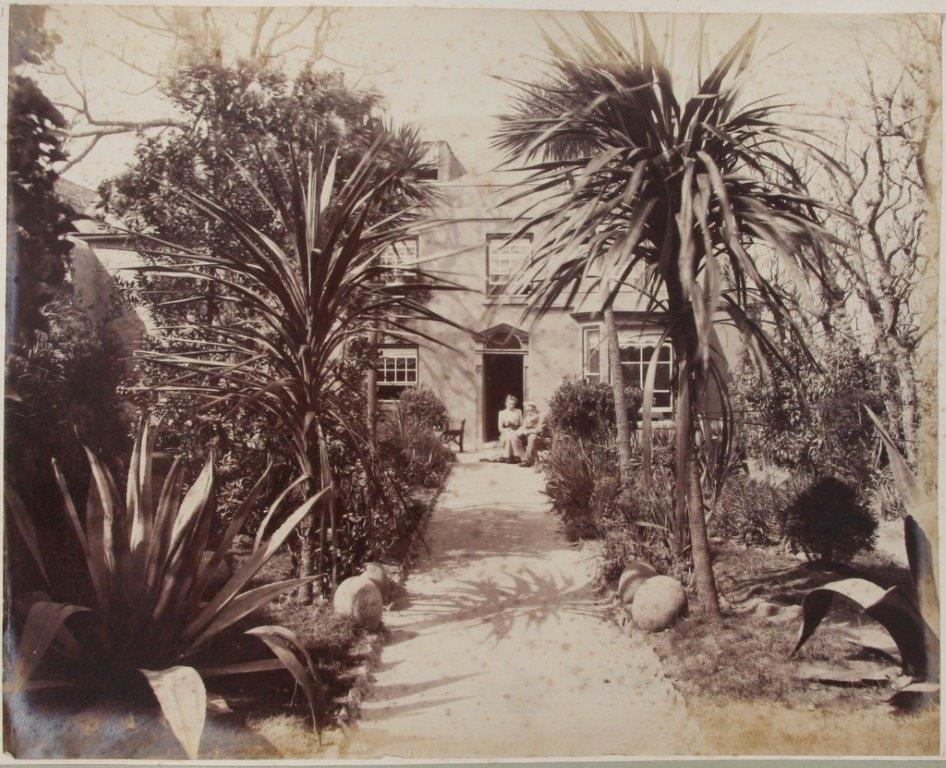

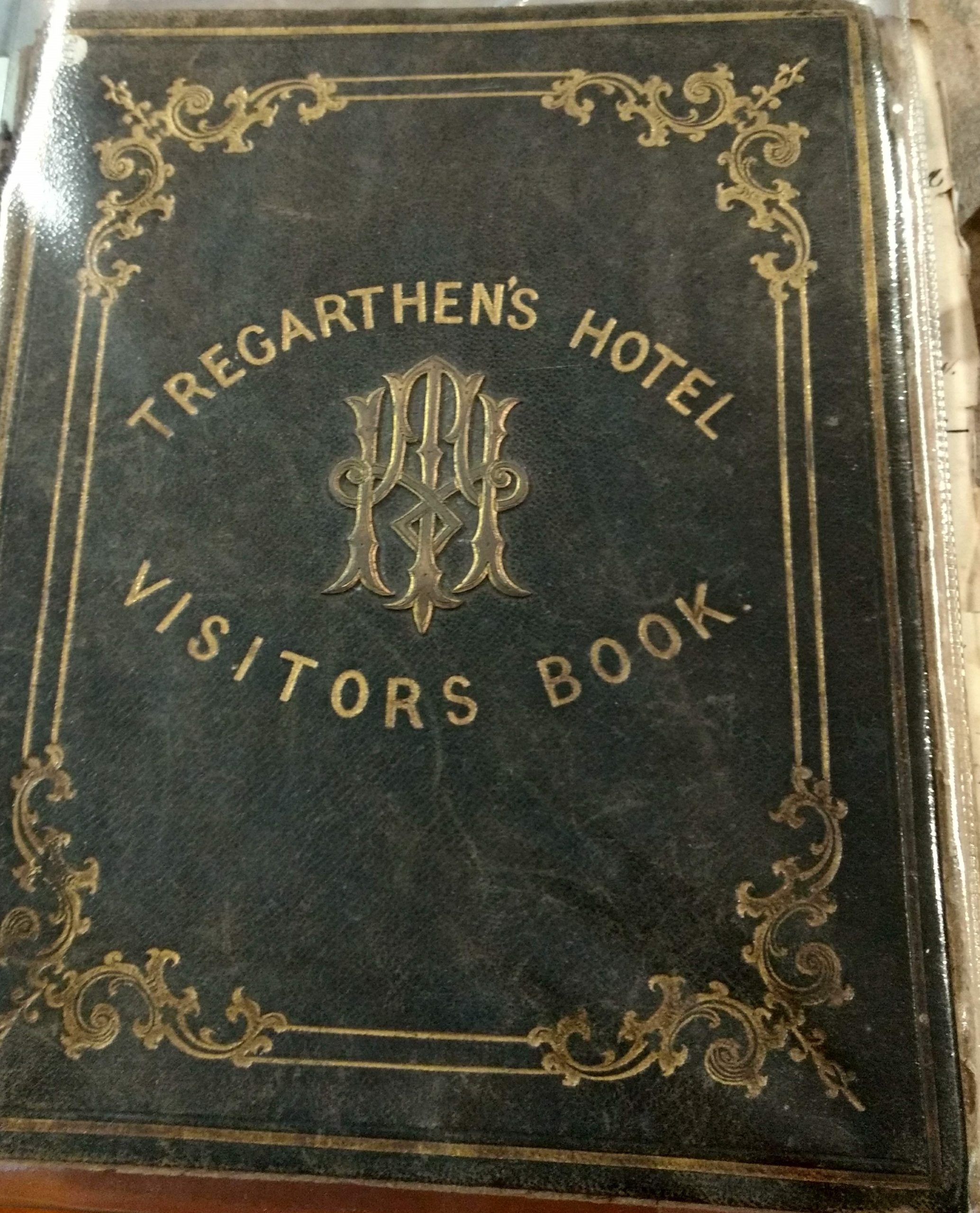

The crossing from Penzance to St Mary’s has always been choppy, even in the summer, as shipping navigates the notoriously ‘rough’ junction of the English Channel and the Atlantic Ocean. It is hard to imagine what Eva’s journey was like in rough winter seas in early January 1891 when she travelled to St Mary’s, the largest island in the archipelago. Depending on the weather, the journey would have taken her at least six or seven hours by cutter, or a little less by a steam packet.6 On arrival she set up home at Tregarthen’s Hotel, the first hotel to be established on the Islands (in 1849) and the home of Captain Tregarthen who ran the steam packet in the mid-nineteenth century.7 Eva must have been particularly fraught and desperate for solitude to have undertaken such a tedious journey.

Whilst Eva had early successes in reorganising nurse training and the nursing department at The London, she was vociferous in her opposition for centralised nurse registration and attracted powerful critics, inside The London, from among the wider hospital and nursing professions, and in the press. During the House of Lords enquiry, Eva was questioned on five separate occasions about her treatment of staff, in particular of probationers. Allegations were made about the power she held to dismiss nurses, that she ‘sweated’ her staff – particularly with their long working hours, and that she sent probationers to undertake the work of trained nurses both in the wards and for the hospital’s Private Nursing Institute. However, despite vocal critics on the hospital’s House Committee, which included Mrs Ethel Fenwick’s husband Dr. Bedford Fenwick, the enquiry supported Eva and found that the nursing department worked well and was ‘thoroughly sound’.8 Unsurprisingly Eva developed a reputation for being extremely forceful, persuasive, dogmatic, and unswerving in her opinion about the development of nursing and nurse registration. But it must have been a gruelling experience – one which persuaded her that the awful journey to the Scilly Isles would be worth it.

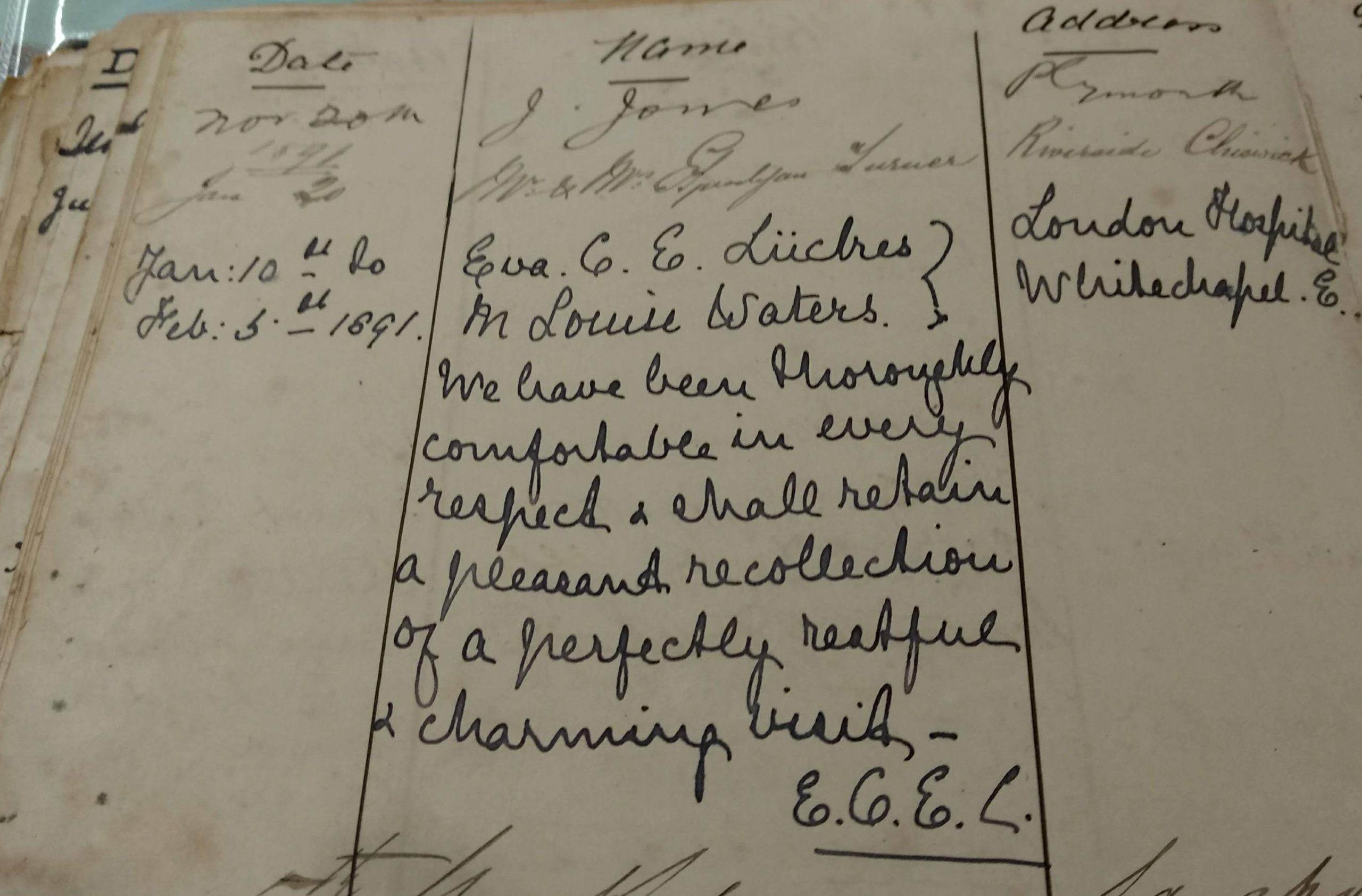

Eva corresponded frequently with Florence Nightingale, her friend and mentor, between 1889-1899, both women often sharing their views about the folly of centralised nurse registration. Florence gave much support to Eva, both through her supportive correspondence, ‘audiences’ and in political ‘manoeuvrings’ behind the scenes. In late December 1890 after months of internal and external criticism a weary and embattled Eva wrote to Florence, thanking her for her support and kindness during the ‘prolonged trial’.9 It was at this point that that she decided to escape to the Isles of Scilly for a complete rest, and for the fresh air afforded by the island’s location. On 2 January 1891 Florence wrote to Eva shortly before she left London, commending Eva’s choice to escape ‘all these troubles’ in a relaxing and restful location which had ‘ever absorbing sea and no post’.10 Accompanied by one of her office assistants, Miss Waters, Eva stayed at Tregarthen’s Hotel, whose other notable visitors had included Alfred, Lord Tennyson.11 The break clearly did her good, and shortly before her departure home Eva wrote to Florence thanking her for her great kindnesses, which had combined with the ‘soothing influences of this beautiful, restful spot’ to considerably refresh her. It seems from her letters that she was reluctant to leave, perhaps wary of the potential criticism and volume of work she would face on her return.12 The Scilly Isles had made a big impact on her, as she described the beneficial effects of the ‘peace and beauty of these fair and charming surroundings’13. On her departure she wrote in the hotel’s visitor book that her visit had been ‘perfectly restful & charming…’.14

Eva returned to the Isles of Scilly on at least one further occasion, in August 1896, when she stayed in a quiet farmhouse just outside the main ‘town’. She wrote again to Florence, describing the beneficial effects of her holiday:

I have rooms in a little farmhouse close to the sea, right away from the town, and find it almost sufficient occupation to sit and watch the changing lights and shades over the other islands – so beautifully grouped around – and the exquisite colouring of earth and sky and sea. All the influences here breathe peace, and I feel as though I had been temporally allowed to take shelter “in the haven where I would be!” I am very weary – I wish fatigue were not so cumulative – but some of it is passing away and I hope these delicious breezes will put a little freshness in before I go back again.15

‘Retreats’ to costal locations in order to escape the pressures of work and critics were to remain as much a feature of her matronship as were her obstinacy and intransigence towards the key issues in nursing. Eva’s health suffered in the ‘poisonous’ fog, grime and squalor of Whitechapel, and she frequently headed to a seafront flat in Bexhill to get way from the London and its environs, often with outstanding paperwork and one of her matron’s office assistants to assist her.16 She remarked that ‘the sea or country are better in the spring’.17 She wrote to her friend Margaret who was taking a break in the Channels Islands at the time, trying to imagine herself not in London but with her friend:

The one thing in favour of your present surroundings [Alderney] seems to be the excellent climate. … I dwell with satisfaction on the clear, crisp air, with all the rough sharpness taken out of it and yet all the freshness left in. I wish I could transport myself there and inhale the atmosphere that would be so reviving after Whitechapel.18

Despite suffering from disabling rheumatoid arthritis, which severely restricted her mobility from at least 1912 onwards, Eva continued to travel to her flat on the front at Bexhill as frequently as possibly, often for long ‘working’ weekends with a member of staff.19 In October 1914 she escaped to Bexhill for her long overdue summer holiday, accompanied in rotation by her assistant matrons, and compassionately acknowledged that they were also exhausted because of the vastly increased workload caused by the onset of World War One: ‘this is the pleasantest arrangement I can make… we are having such lovely weather. I am able to live on the balcony, and to have all my meals, except breakfast, out of doors’.20

Her last surviving letters, which she wrote to Margaret in the spring of 1918 reveal her desire to be by the sea, despite the immense effort required to travel there with a life-limiting illness and chronic disabilities: ‘I am better for the quiet week here [in Bexhill]…’, she wrote.21

In her letters to Florence and Margaret, Eva often praised the recuperative powers of the natural world. They reveal a more human side to her than previously presented; they show how Eva yearned and craved for the physical and psychological boosts these seaside breaks provided, throughout her tenure as matron. ‘The sea brings me freshness and carries away trouble in a way that nothing else equals’, she wrote to Margaret in August 1912, ‘I love the country too, but if it must be one or the other, the sea comes first’.22

It seems fairly clear that these seaside visits enabled Eva Luckes to continue as matron until her death, in 1919, despite being under huge pressure from work, and later from ill-health. She worked until the end of 1918 and remained ‘nominally’ matron until her death in 1919. She died of chronic nephritis and uraemia at her own hospital, The London, on 16 February.23

References

- Susan McGann, The Battle of the Nurses: a study of eight women who influenced the development of professional nursing, 1880-1930 (London: Scutari Press, 1992).

- Eva’s surviving letters to her friends virtually span the period 1889-1918: her correspondence with Florence Nightingale survives from 1880-1899, and to Margaret Paul from 1903-1918; The British Library, Add MS 47746, The Nightingale Papers, Vol. CXLIV, Correspondence with Eva Charlotte Ellis Lückes, Matron of the London Hospital; 1889-1899: Correspondence with Florence Nightingale: 1889-1899; RLHPP/Pau/1/1-51, Letters to Margaret Paul.

- Grainne Anthony, ‘Distinctness of Idea and Firmness of Purpose. The Career of Eva Luckes; A Victorian Hospital Matron.’ (Unpublished MA dissertation, London Metropolitan University, 2011).

- Isles of Scilly Museum, Tregarthens Hotel Visitor Book, 10 January 1891- 5 February 1891, n.p.

- House of Lords Select Committee, Metropolitan Hospitals, Provident and other Public Dispensaries and Charitable Institutions for the Sick Poor, Third Report including Proceedings of the Committee and Minutes of Evidence, June 1892, accessed via ProQuest, 22 May 2019.

- J. G. Uren, Scilly and the Scillonians, (Plymouth, no location, 1907- reprinted 2019), 62.

- https://www.tregarthens-hotel.co.uk/about-tregarthens/history, accessed 10 January 2020; It was not until 1927 that there was a dedicated passenger ferry to the islands.

- RLHLH/A/17/49, Report of the House Committee, 3 December 1890, 12.

- The British Library, Add MS 47746, The Nightingale Papers, Vol. CXLIV, Correspondence with Eva Charlotte Ellis Lückes, Matron of the London Hospital; 1889-1899: Correspondence with Florence Nightingale: 1889-1899, ff. 13-17, 20 December 1890, London Hospital, E.

- RLHPP/LUC/1/4, Letter from Florence Nightingale to Eva Luckes, Claydon, 2 January 1891.

- Isles of Scilly Museum, Tregarthens Hotel Visitor Book, 10 January 1891- 5 February 1891, n.p.

- The British Library, Add MS 47746, The Nightingale Papers, Vol. CXLIV, Correspondence with Eva Charlotte Ellis Lückes, Matron of the London Hospital; 1889-1899: Correspondence with Florence Nightingale: 1889-1899, ff. 18-19, Tregarthens Hotel, Isles of Scilly, 3 February 1891.

- The British Library, Add MS 47746, The Nightingale Papers, Vol. CXLIV, Correspondence with Eva Charlotte Ellis Lückes, Matron of the London Hospital; 1889-1899: Correspondence with Florence Nightingale: 1889-1899, ff. 18-19, Tregarthens Hotel, Isles of Scilly, 3 February 1891.

- Isles of Scilly Museum, Tregarthens Hotel Visitor Book, 10 January 1891- 5 February 1891, n.p.

- The British Library, Add MS 47746, The Nightingale Papers, Vol. CXLIV, Correspondence with Eva Charlotte Ellis Lückes, Matron of the London Hospital; 1889-1899: Correspondence with Florence Nightingale: 1889-1899, ff 324-327, Porth low St Marys, Isles of Scilly, 24 August 1896.

- RLHPP/PAU/1/3, London Hospital, E., 30 December 1904; RLHPP/PAU/1/11, London Hospital, E., 23 January 1911.

- RLHPP/Pau 1/1, Letter to Margaret Paul, London Hospital, E., 23 July 1903.

- RLHPP/Pau 1/50, Letter to Margaret Paul, London Hospital E., 7 April 1918.

- RLHPP/PAU/1/13, Letter to Margaret Paul, London Hospital, E.,14 March 1912 Eva is also said to have had Diabetes, see Susan McGann, The Battle of the Nurses: a study of eight women who influenced the development of professional nursing, 1880 – 1930 (London, Scutari Press, 1992).

- RLHPP/Pau 1/29, Letter to Margaret Paul, Bexhill on Sea, 6 October 1914.

- RLHPP/Pau 1/51, Letter to Margaret Paul, Bexhill on Sea, 24 May 1918.

- RLHPP/Pau 1/17, Letter to Margaret Paul, Bexhill on Sea, 30 August 1912.

- General Record Office death certificate for Eva Luckes,16 February 1919; Grainne Anthony, ‘Distinctness of Idea and Firmness of Purpose’, 90.