| Sue Hawkins, The National Archives, UK | The UKAHN Bulletin |

| Volume 8 (1) 2020 | |

I am currently working on a project at The National Archives called In Their Own Write (ITOW). ITOW is using a series of nineteenth-century letters and communications, called MH 12, which contains thousands of volumes of correspondence between the Poor Law Board (and its various iterations) and the local Unions. The purpose of the project is to locate letters from the poor and paupers. These letters are few and far between, but represent a very rare collection of material in which the poor speak for themselves. It’s a great project to work on as MH 12 contains material on a host of subjects (in addition to the poor’s letters), including nursing. So in the process of surveying volumes for the project (and given my interest in history of nursing) I can’t help but notice correspondence about and by nurses and nursing in the workhouses; and if I have time I make a note or take the odd photo and put it by for future use.

This short piece (which is at the ‘work in progress’ stage) resulted from one of those ‘I am sure this might be interesting’ moments, and exemplifies what I love about archive work. It is a story (with more gaps at the moment than I would like) of a woman who worked for a short period of time in the 1860s as a nurse at the Huddersfield Workhouse. Her application form is among the papers – as are the application forms for hundreds (if not thousands) of workhouse nurses – but she attracted my attention because she said she was born in Kingston, Jamaica. In another life, I taught British 19th century social history at Kingston University (London not Jamaica!) and was always on the look-out for stories of black Britons in the Victorian era to introduce to my ethnically-diverse student group. These stories are incredibly hard to find; Victorian government, well known for its obsessive collection of information and compilation of statistics, seemed totally uninterested in race or ethnicity of the population. There was no question about race in the decennial census, and although country of birth was recorded, if outside England and Wales, this tells you nothing definitively about ethnicity. Needless to say I never found the case studies I hoped for: there was an African princess who Queen Victoria ‘adopted’, the first black professional footballer, Arthur Wharton (1865-1930), and of course the other famous Crimean ‘nurse’, Mary Seacole (1805-1881), but not many others. So when Frances Yonge’s application turned up, showing her birth as Kingston, Jamaica, my interest was piqued.

Of course, being born in Jamaica doesn’t necessarily mean she was of black heritage. So I read on, hoping somewhere on the form there would be further clues to her ethnicity. There were not! But there were other interesting things about her: she claimed to be a widow, with two very young children (aged 2 and 4); she was currently working as a rag-sorter in a mill in Holmfirth (how did she get there from Jamaica?) and living at Wooldale Hall (also a surprising detail – what was a rag sorter doing, living in such a grand sounding house?). She admitted she had no formal experience of nursing, but she could read and write and follow medical instructions. She had been in Holmfirth about six months, having arrived there it seems from Liverpool, where she had been abandoned by her husband who brought her there (with her mother and children) from Jamaica. A note on the application, added by the clerk, said she was lately married to an officer on the Alabama, who had brought her to the UK but had since deserted her. She had recently discovered her marriage was bigamous, and her husband had a family back in the USA. (MH 12/15018/33199)

Frances got the job (she was the only applicant) and the Board of Guardians reported her to be ‘very intelligent’. A newspaper report of her appointment added a few more detail: she had been a widow in Kingston, Jamaica where she ran a boarding house with her mother, and it was here she met and married Yonge, who was her lodger. He had represented himself as a single man, and proposed marriage which she accepted. He then proceeded to get ‘possession of all her property and the took her to Liverpool – as she imagined on their way back to America.’ [Yonge was an American citizen.] But once at Liverpool he abandoned her, leaving her destitute. (Huddersfield Chronicle, 20 August 1864).

I carried on looking through the volume of MH 12 for Huddersfield and found more entries relating to Frances Yonge. She started work as a nurse in the Workhouse on 26 August 1864, on a salary of £20 pa with rations. Hopefully, Frances had found some security, with a steady income with which to care for her children and mother, in this strange land. Then out of the blue, on 31 December 1864, she received a brief letter from the Board of Guardians informing her she was to be dismissed for the ‘unsatisfactory manner in which her duties were discharged’. She was to leave at the end of the month, but on receipt of the letter she immediately quit the workhouse. As she said later, in explanation, ‘my motive for leaving before the date of my dismissal I was afraid of worse ill-treatment’. (MH 12/15018/578)

And bad treatment she had received – if her story is to be believed. It was not unusual for nurses to come and go in quick succession in workhouses; this turnover of staff was just one of many complaints about workhouse nursing at the time. Most went quietly – but Nurse Yonge did not. Sometime in early January, after receiving the letter of dismissal, Yonge wrote to the Poor Law Board in London to complain about her treatment. She had been given no concrete reason for her dismissal, and stated she wished to bring various charges against the Institution, especially in relation to the workhouse diet. In her letter she described the diet and wrote ‘it made my heart bleed’, that the paupers ‘must eat or leave what is given’. The Poor Law Board wrote back to her saying they would look into the matter, and despatched one their Inspectors, Mr Corbett, up to Huddersfield to see what was going on. (MH 12/15018/1116)

From Frances’ point of view, Corbett’s subsequent report was damning: he spoke to all the sick inmates and the only complaints he found were about the nurse, Frances Yonge. He concluded she was ‘a heartless, worthless woman’, who neglected the inmates and used the ‘coarsest and abominable language’. Furthermore, she was accused of trying to entice a ‘poor girl’ to leave the workhouse with her to go to Sheffield, to a ‘house of ill fame’. (MH 12/15081/1116B, 18 January 1865)

A report in the local newspaper shed some light on why Yonge had been sacked. It recounted an incident which had occurred in late December, during the process of removing an inmate from the workhouse to the asylum at Wakefield. The workhouse inmate had been put in a cab to be removed to the asylum, but was found to be without shoes and socks. As Frances Yonge had been tasked with getting her ready, she was blamed for this rather inconsequential state of affairs, even though everyone present had testified that the woman had been violent and had taken her shoes off and thrown them out the cab window. Nevertheless, the event was used as an excuse to dismiss Yonge: I can’t help feeling they were looking for one. ((Huddersfield Chronicle, 14/11/1865)

That ought to have been the end of it. A new nurse was recruited immediately to replace Yonge and the incident should have been over. But on 23 January, Frances Yonge wrote again, angered by the insult to her character caused by the Inspector’s report and determined to have the ‘truth’ come out.

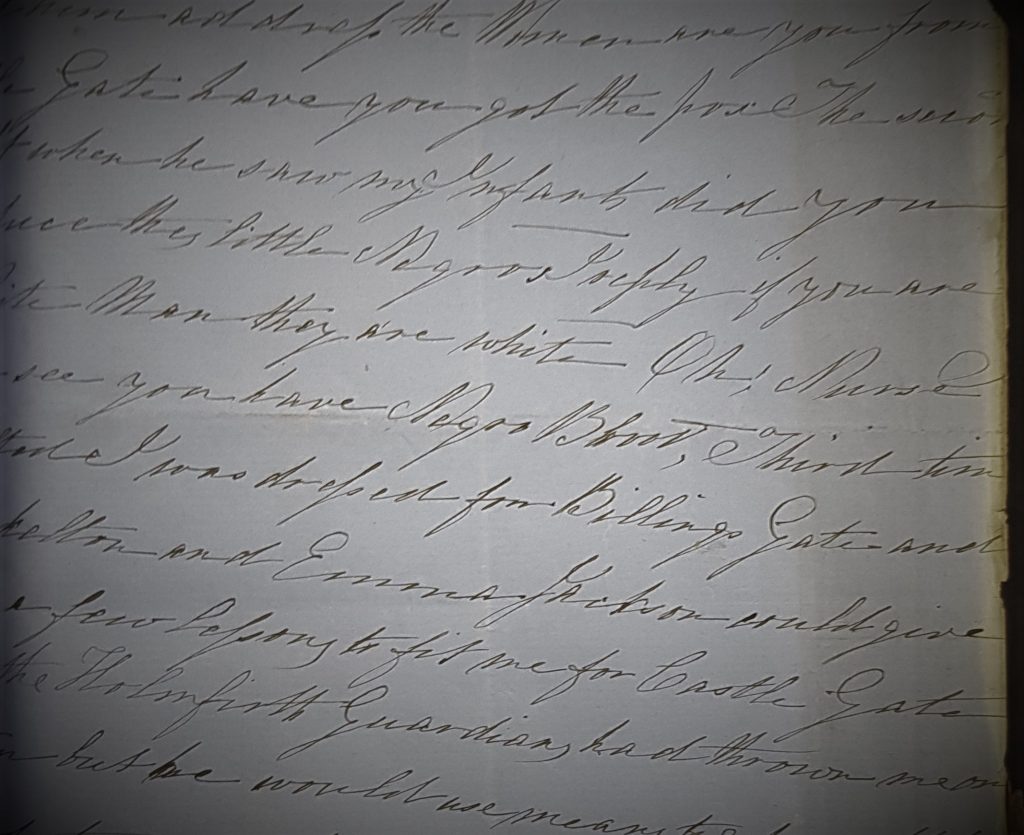

This letter was of an altogether different tone. It rages and jumps across a number of accusations, randomly moving forward and back in Yonge’s narrative of events. She hurls accusations at the Matron, who she claims mistreated her badly and caused her life to be a misery. On one occasion, when she tried to complain to the matron about ‘the vulgar language of Surgeon Rhodes to me’, Mrs Sykes threatened to kick her out; her husband, the Workhouse master, reiterated the threat: ‘get out of here, away with you or I will kick you out’, he shouted. She accused other members of the staff of abusing her in a similar manner. Even the Matron’s children abused her, telling her to ‘shut the door and stay on your own side’. However, this was nothing compared to the treatment she claimed to have received from Mr Rhodes the surgeon. Some of what he was alleged to have said is difficult to read today: ‘when he saw my infants’ wrote Yonge, he said ‘did you produce little negros … Oh Nurse, I can see you have negro blood’. And then he proceeded to make dreadful accusations about her, ‘I can see from your eyes that want a man badly and John Thomas in you for you cannot keep your legs shut’. On another occasion he suggested she get lessons to ‘fit me for Castle Gate’. [Castle Gate was renowned for its brothels and houses of repute.] Yonge lashed back at him (she was not to be easily intimidated), ‘God created me it is of no consequence what you think’. The letter contained other accusations about Rhodes’ treatment of women generally, and of other goings on in the workhouse. (MH 12/15081/3065)

And so now here was an indication that Frances Ann Yonge was probably a black woman, and not only that, but a black woman prepared to stand up for herself against what would seem to be ingrained racial prejudice, amongst not only the workhouse staff and Guardians but amongst the paupers too. Further evidence as to her ethnicity appeared in reports of a trial in which her erstwhile husband gave evidence for the Crown: attempting to discredit his character the defence lawyer accused him, among other things, of marrying a ‘mulatto’ woman. (The Times, 24 June, 25 June, 5 November 1863)

Frances’ back story (and that of her husband) is slowly being revealed and it is fascinating, but not ready to be written up yet in full. I had not expected this short Workhouse application form to lead to such an incredible tale which brings in the American Civil War, the construction of ships for the Confederate Navy in Liverpool (the Alabama in turned out was part of this story), pressure by the Union Government on the British Government to break its neutral stance on the war and accusations of espionage. And that is the wonder and fascination of archives research!

But I also think the story, and Frances’ two letters, are of great importance for the history of black people in nineteenth-century England. Such material is rare (as far as I know), and if similar documentary evidence exists (which surely it must), it is rarely catalogued as such, making it almost impossible to find except through serendipity. The ITOW project is incredibly important for revealing the inner lives of the nineteenth-century poor in a way other material cannot: it is also important because it reveals how the lives of other groups hidden from history might be revealed through the process of detailed surveying of apparently bureaucratic collections such as MH 12, looking for instances where the interests of people from below intersect with the interests of government.

And what happened to Frances Yonge? The Poor Law Board dismissed Yonge’s complaints as those of a mad woman and an unreliable witness, and no further action was taken. I have found her subsequently in another Workhouse, this time in Sheffield in 1866, sadly as an inmate. She was in court again accusing workhouse officials of abusing her, and again, she was accused of being a mad woman and was being threatened with the asylum. (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 13 October 1866) What happened next in Frances Yonge’s life is still be uncovered: the search continues!