| Liesbeth Hesselink, Independent researcher |

The UKAHN Bulletin |

| Volume 10 (1) 2022 | |

Djarisah was not only a professional midwife but a woman with modern, emancipated ideas about the position of indigenous women. In a speech she set out her vision as follows:

Now, we women are awake too, and we will roll up our sleeves and actively set to work. And know this also, that men regard us as flowers: beautiful, sweet-smelling flowers are picked by men, but ugly and foul-smelling ones are not even deemed worthy of a glance. Therefore, sisters, onwards to the golden freedom via the road of education![1]

This, in a nutshell, is the essence of her working life: women were to elevate themselves through education. She herself was a shining example of what she preached.

Introduction

This article focuses on a remarkable indigenous woman, the Javanese midwife Djarisah, whose ethnic origins would never have ranked her with the elite, yet who firmly belonged there through her own effort. She lived in a time of colonialism and in a country where education and emancipation were far from matter of course for a Javanese woman. Djarisah was an example of the Ethical Policy, the official Dutch-government colonial policy implemented for a brief period (1900-1920) that addressed and aimed to improve the well-being and welfare of the indigenous population, using a Western-style model.[2] Central to it was the elevation of Indonesians, men as well as women. The new course that the colonial policy was steering resonated with the indigenous elite.

The aim of this article is to promote scholarship on the history of non-Western women in the colonial setting of Dutch-controlled Java in the early twentieth century. The sources used are primarily from Dutch-language newspapers from the Dutch East Indies, besides reports and suchlike from the then colonial government. They also include sources from Djarisah herself; her writings demonstrate her endeavours to emancipate herself and her compatriots by promoting primary as well as vocational education.

Before discussing the education that Djarisah received herself, perhaps a brief explanatory note on Dutch colonial East Indies is useful. The Dutch East Indies represented the highest population of Muslims in the world, much like Indonesia today. In the colonial era Indonesian women did not wear the veil and it was only girls from the higher classes that were kept in isolation from their twelfth birthday.[3] This is in marked contrast with the situation in former English colonies such as India or Pakistan. Most Europeans in the colony were of mixed descent, i.e., children by European man and indigenous woman, Eurasians, in short. If the father acknowledged the child, it had the legal status of a European.

Education and training

Djarisah was born in Mojowarno (East Java) on 11 February 1880.[4] Mojowarno was a Christian community, and as such a success story for the Dutch Protestant mission.[5] The thriving community not only boasted the usual church and ordinary primary school but also a teacher training college, a technical school and a hospital.[6] The mission sought not just to convert the indigenous population to Christianity; far beyond that aim, it aspired to provide education and healthcare. Both boys and girls growing up in this Christian community received education, and Djarisah in Mojowarno was no exception.[7]

Around 1900, 30 million indigenous people lived on Java, meaning there would have been about 15 million women, assuming an even ratio of male to female births.[8] Of these 15 million women, only around 16,000 (that is 0.1 %) had received some form of education in 1910; almost all these girls belonged to the nobility (priyayi).[9] Figure 1 illustrates how unique it was for an ordinary Javanese girl like Djarisah to be able to read and write.

| 1910 | |

| Public European Education (primary) | 439 |

| Private European Education (primary) | 57 |

| Public Indigenous Education (primary) | 5656 |

| Private Indigenous Education (primary) | 4690 |

| Desa (village) schools | 5114 |

| Total | 15,956 |

Figure 1: Number of girls receiving education on Java around 1910[10]

Indonesians had few if any opportunities for further education, and girls had none, but around the time that Djarisah had finished school, the government developed a new follow-up training course exclusively meant for indigenous girls: the midwifery training.[11] The government thus hoped to obviate the need for dukun bayi, the indigenous midwives, who were deemed to lack expertise. So, after leaving school in Mojowarno, Djarisah started her training to be a midwife in 1897.

Traditional birth attendants, dukun bayi

In the indigenous society, the birth of a child was attended by dukun bayi, traditional birth attendants (TBA). Every village would have one or more dukun bayi. A dukun confirmed a woman’s pregnancy once her period had skipped three months and she would perform various ritual acts up to the moment of the actual childbirth. The birth itself was also surrounded with rituals. After the birth, she often remained to help out for forty days, not only caring for the mother and child but also doing household chores. Dukun could not have lived from what they received by way of compensation, which was a small amount of money and occasionally some food besides. Theirs was a part-time job. The dukun bayi derived their reputation among the indigenous populace from their usually advanced age, which meant that not only had they assisted at numerous deliveries, they were mothers who had had several children and knew the intimate details of child birth.

European physicians in the Indies were almost without exception very negative about the knowledge and the skills of the dukun bayi; and as early as 1817, the Dutch colonial government attempted to replace the dukun bayi with indigenous women who were trained as midwives. In 1851 it founded a midwifery school in Batavia where indigenous girls were given Western-style training in midwifery. The idea was that they would make the dukun bayi redundant. In actual practice, however, they never managed to establish a foothold: the indigenous population continued to prefer their trusted dukun bayi. The certificated midwives were young women who mostly did not have any children of their own and, even more importantly perhaps, who only offered their services at the time of the birth and in the following week. This was in sharp contrast to the dukun bayi: old women who arrived long before the baby was due and continued to help until well after the birth. The government decided to close the midwifery school in 1875 when it became clear that its aim – replacing the dukun bayi with Western-trained midwives – had not been achieved.[12]

The image in Figure 2, although from a much later date, 1930, shows the marked difference between the dukun bayi (on the right) and the midwives (on the left) which would also have been apparent in the late nineteenth century. The dukun is an elderly woman, dressed as a village woman with her instruments (herbs, rice, an egg) on the table in front of her. The midwives, in contrast, are young, wear white uniforms and display their ‘more modern’ instruments (obstetric stethoscope and white, hygienic towels).[13]

After endless discussion whether the school should be reopened or whether a form of home-training should be offered, the government decided, in 1891, to opt for the latter. A limited number of European physicians were permitted to train indigenous young women to become midwives in two to three years. The physicians received a monthly subsidy for the student’s board and lodging and a high bonus for each student who passed the exam. In practice, it was not easy to find enough physicians with sufficient deliveries in their practice – after all, indigenous women much preferred a dukun bayi and most definitely did not want to have a man present when they were giving birth. Neither was it simple to find suitable students; the ability to read and write was a prerequisite for admission to the course. The exam programme largely corresponded with the programme for European midwives, except for a somewhat simplified version of the theoretical knowledge component.[14]

Towards the end of the nineteenth century a mere two physicians on Java, missionary doctor H. Bervoets in Mojowarno and civil physician in Kediri (East Java) H.B. van Buuren, each trained four young women to become midwives. Two of Van Buren’s students were from Mojowarno, one of whom was Djarisah.[15] The distance between Mojowarno and Kediri, 40 kms, may not seem very great to modern people like us. Yet in those times, it was a huge step for a single, young woman to leave her birthplace and parental home. Indigenous young women almost always stayed at home with their parents until they married.

Two years later, in 1899, all four of Van Buuren’s students passed the exam.[16] Around 1900 the total number of indigenous midwives who had taken the exam across all of the Dutch East Indies was 42.[17] This may not sound like a very large number, given the population numbers discussed above, but, as the vast majority of indigenous women chose to be attended by a dukun bayi during their pregnancy the demand was not high. The clientele of the newly qualified indigenous midwives tended to be Chinese, Eurasian and European women.

Djarisah’s early career as a midwife in Kediri and Cirebon

Having passed her exam, Djarisah continued to work with her tutor in Kediri.[18] Van Buuren had managed to get government permission to carry out an experiment and with the support of local administrators – the Dutch resident and the Javanese regent – he tried to prevent dukun bayi from continuing to work as midwives in Kediri. Dukun were rewarded when they placed a pregnant woman with a certificated midwife (and fined when they did not) and were only allowed to provide post-natal maternity care. The experiment proved a failure.[19] Later it emerged that Djarisah’s views on dukun bayi were greatly inspired by Van Buuren. Much like her tutor, she argued that dukun bayi should be forbidden to practise midwifery.[20]

After Kediri, Djarisah set up as a midwife in Cirebon (West Java), a place some 580 kms (360 miles) from Mojowarno. To encourage certificated midwives to treat poor pregnant women gratis, the government provided midwives with an allowance. Djarisah was among those who received such an allowance but the government scheme was soon discontinued.[21] Not discouraged by this, Djarisah continued to practice, free to treat and charge pregnant women for her services. Van Buuren kept in touch with her, and in one of his publications, he described thirty-nine childbirths from her practice, praising her expertise very highly.[22]

Bandung

As mentioned above, the government annually permitted certificated midwives to provide obstetric care to poorer women free of charge, for which they then received an allowance.[30] This free care was meant for all poor women – European as well as indigenous. When a grateful father in Bandung once thanked a lady via the newspaper for free obstetric assistance when his wife was giving birth, one of the qualified midwives was quick to take up her pen. It was exactly because the case involved a European woman that the impression might have been conveyed that she had been a qualified midwife, something which was not true; she turned out not to have the legally required certificate of competence. The letter writer stood up for all her colleagues, both European and indigenous midwives. The editors agreed with her: the happy father should have spoken of ‘assistance at childbirth’ rather than of obstetric care. The editors seized upon this incident to clarify the arrangement once more: ‘A grateful person, who in his gratitude forgot the law, has meanwhile caused attention to be focused on useful regulations that have proved to be too little known.’[31] Obviously, the matter concerned a pregnant European woman who had received some support and assistance from another European woman, possibly a neighbour or a friend, as she was giving birth. The letter writer would never have taken up her pen to complain about a dukun bayi; after all, these did not constitute rivals in her eyes.

Over time, the indigenous population gained somewhat more confidence in Western midwifery. They were even prepared to pay for the care provided, and went far in this: ‘The common man is not even reluctant to bring something to the pawnshop to cover expenses.’[32] Djarisah intended to use this turnaround to her own advantage and open a clinic for poor indigenous expectant mothers. A plot of land had even been made available, but there was as yet no budget. She had a fundraising appeal for her clinic-to-be printed in the newspaper, but it was to no avail.[33]

Djarisah was very ambitious when it came to her profession. In 1912 she went to the Netherlands on her own initiative, and obtained the Dutch midwifery certificate in Rotterdam.[34] Back in Bandung, she resumed her practice.[35] She was also one of the very few midwives in the Indies to have taken out a subscription to the Dutch-published Tijdschrift voor praktische verloskunde; hoofdzakelijk ten dienste van vroedvrouwen (Journal for practical obstetrics; principally for midwives).[36] Her tutor in Rotterdam, K. de Snoo, may have been influential here; he contributed to the journal on a regular basis.[37]

In addition to her work as a midwife, Djarisah made her voice heard in various other ways, becoming something of a social activist.

Incident in the train

The first time Djarisah spoke up in public was in a letter to the editors of the newspaper De Expres, in December 1913. She had experienced discrimination when travelling on a train, which she had suffered in silence but now bit back at the perpetrator in a letter.

Dear Sir, I politely request that you grant the following a modest place in your well-read paper. Last Sunday, I returned to Bandung, after having visited a patient in Cirebon. I was travelling 2nd class; since the compartment was packed with travellers, I was forced to take a seat in the dining car. It appeared as if the European fellow passengers could not accept that a woman dressed in Javanese style dared sit among them. They thought I did not understand Dutch, and many insults and not so pleasant names were thrown at me in Dutch. Many a shoulder was raised in contempt, with the remark that the brown woman had no right to be there. I pretended not to understand anything, until I had to change trains, once we had arrived at Cikampek, and I thanked the ladies and gentlemen present politely for the compliments they had paid me. None of them dared to raise their eye to me. Thank you, Mrs DJARISAH accoucheuse.[38]

She signs her letter ‘Mrs’ with remarkable confidence; ‘accoucheuse’ is a fancier, smarter synonym for midwife. The editors placed her letter under the title ‘Typical manners’. An anonymous letter writer in De Expres recognised the incident as one of those innumerable ‘Samples of current indignities (…), known to every-one, and encountered daily.’[39] Six months later, the editor-in-chief of De Expres, E. Douwes Dekker, a great-nephew of the famous writer Multatuli, mentioned the incident to illustrate the frequently antipathetic attitude of the Dutch.[40] In a letter to the editor, an indigenous woman pointed out that, wearing European-style clothes, as she did, would pre-empt similar obnoxious treatment from train guards. ’As a rule, a European guard thinks he can do as he pleases with Natives. Now that I have taken to wearing European clothes, I have experienced no more unpleasantness and I can move around freely, wherever I want to.’[41] At the time of the train incident, Djarisah was wearing sarung and kebaya; it is not my impression that she changed her habits on account of the event.

It is interesting that while East Indies newspapers would frequently borrow articles from each other, Djarisah’s letter to the editor was not, notably, taken up by other papers. Editors may not have judged this ‘incident’ as newsworthy, precisely because it occurred so often. That it was De Expres that provided a platform for the letter and the reactions that subsequently followed can be accounted for through the fact that it was the mouthpiece of De Indische Partij (The Indies Party). This was the first political party to serve the interests of both Indonesians and Eurasians. Its editor-in-chief, Douwes Dekker, also one of the founding fathers of De Indische Partij, was himself a Eurasian. To his eyes, there was just one contrast that mattered: that which existed between oppressor and oppressed, between the Netherlands and all the inhabitants of the archipelago who, regardless of race, religion or wealth, wanted to put their best efforts into developing the country.[42]

These reactions demonstrate that Djarisah was certainly not the only Indonesian person to have experienced this kind of discrimination at the hands of Europeans and Eurasians. Some Indonesians put up resignedly with this behaviour as an inevitable part of colonial society, others must have cursed it among themselves. But openly denouncing such treatment as Djarisah did in her letter to the paper was exceptional. Her experiences in the Netherlands may have played a role here. Just like other Indonesians who were in the Netherlands around the same time, she would probably have realised that a Javanese woman, such as herself, was treated with respect in that country.[43]

Fight against immorality

Around 1900, morality – or rather, immorality – became a social issue in both the Netherlands and in the Indies, among Europeans as well as Indonesians. Immorality, of course, referred to the conduct of certain women; these not only included prostitutes but also concubines (nyai) – indigenous women who were not married but lived together with European men. Concubinage was initially seen by the colonial rulers as a necessary evil, given the under-representation of European women in the colony: there were 636 women to every 1000 men in the European population group of around 1900.[44] Men therefore had to resort to indigenous women to relieve their sexual urges, was the widely held view at the time. It has been said that concubinage involved half the European men, and occurred in all walks of life.[45]

In both the Netherlands and the colony, all kinds of organisations addressed the issue of immorality, including the Nederlandsche vrouwenbond tot verhooging van het zedelijk bewustzijn (Dutch Women’s Association for the Promotion of Moral Conscience) and the Vereeniging tot Bevordering der Zedelijkheid in de Nederlandsche Overzeesche Bezittingen (Society for the Promotion of Public Morality in the Dutch Overseas Colonies).[46] Under pressure from these societies, concubinage came in for more and more criticism, and concubinage between European men and their Indonesian housekeepers (nyai) became outdated.[47] In 1911, The Netherlands introduced new public morality acts which came into force in the Indies in 1913.

Around the same time – the early twentieth century – the first nationalist organisations emerged in the Indies and these too concerned themselves with the position of women. The nationalist parties were fiercely opposed to concubinage. In their view, the practice embodied both colonial exploitation and an ethically improper form of cohabitation.[48] In 1912 the nationalist organisation, Sarekat Islam (Islamic Association), was founded. After one of its members, Raden Muso,[49] raised the issue of morality at a meeting of the Bandung branch of Sarekat Islam in 1914, a separate society was set up to address it: Madju Kemuljan (moral progress).[50]

Madju Kemuljan

Djarisah certainly agreed with the aim of the new organisation, Madju Kemuljan, to prevent and combat immoral behaviour in general, and, more specifically, to fight concubinage and the trafficking of women. Victims would be given moral as well as financial support. The society hoped to achieve its goals by distributing tracts and holding meetings.[51] Its board consisted of prominent Europeans, Indonesian nobles (priyayi), and Djarisah, who became its deputy-treasurer. While Djarisah did not belong to the nobility, her profession made her stand out: newspapers termed her ‘a well-known Native woman’;[52] in short, she was no ordinary indigenous woman.

The inaugural meeting was attended by 600 people; in other words, this was a momentous event, a happening.[53] Each board member gave a speech during the founding meeting. Djarisah’s roughly went like this:

A woman must not sit still, while the man is making every effort to master some profession. A woman can do this just as well, if only she puts her mind to it. A girl should not waste her youth waiting for Mr Right, only to be married to him, and when fate later causes them to separate, she should not, as a divorcee, merely be looking around for yet another candidate, simply because she cannot do anything that will help her earn a living.[54]

Vocational training for women would be the solution, Djarisah believed, by which they could ultimately be completely independent from men. After her speech, someone in the audience was reported to have whispered that he completely agreed with her aspiration, ‘provided it does not turn our wives into suffragettes’.[55]

According to Djarisah, the words spoken at the inaugural meeting not only greatly affected the women attending it but also those who heard of it. ‘Time and time again, they hear the rousing words of uplift and the call to obtain knowledge in order to no longer be deluded by men about things that we, women, can and should know for ourselves.’[56]

Various media in both the Netherlands and the colony reported on the founding of Madju Kemuljan;[57] one described it as part of the fight against prostitution in the Indies.[58]

The board of Madju Kemuljan did not stop at meetings and noble words. They followed them up with actions to help achieve their goal. On one occasion, Djarisah, together with a male board member, tried to prevent an indigenous girl, the daughter of a babu (housemaid) at a European family, from falling into the hands of women traffickers. They visited the girl at home and tried to talk her out of accepting an Englishman’s proposal that she became his ‘housemaid’ in return for a hefty sum of money. Their attempts to convince her proved successful, and the girl decided not to take up the offer.[59]

The board’s plan to set up a batik school was successful.[60] Less auspicious, however, was the start of the course for indigenous midwives. Unsurprisingly, Djarisah sat on the committee that was to prepare the course. The board requested that the government finance the course; a subsidy, however, was never given.[61] Could this have been such a great disappointment to Djarisah that she did not attend the next meeting of Madju Kemuljan? Moreover, it emerged that the subscription fees had not been collected for over a year; as the deputy-treasurer, this had been Djarisah’s task.[62] A year later, in 1916, the society’s chair and spiritual leader Raden Muso stood down.[63] During their meeting in 1917 the board denied rumours that the society was defunct, although it did admit that it was ailing. Ambitions had to be adjusted: the fight against prostitution was beyond their powers and the society was to limit itself to helping the female victims of trafficking.[64] Since then, nothing has been heard of Madju Kemuljan. Djarisah had probably abandoned the sinking ship earlier.

Declining welfare report

Djarisah once again made her voice heard as she advocated for women’s education in the context of a new colonial policy, the Ethical Policy. In the annual Royal Oration of 1901, Queen Wilhelmina announced that the Netherlands as a Christian power was obliged to imbue government policy with the understanding that the Netherlands had to fulfil a moral mission towards the people of these territories. Therefore, politics should raise the population mentally and materially to a higher level of development, according to the Western model.[65] In her Oration the Queen focused attention on the declining welfare of the indigenous population, and announced plans for an investigation into the matter.[66] Declining welfare was the term adopted for what, in fact, was a description of the deplorable economic situation of the indigenous population. H E Steinmetz (Resident of Pekalongan (Central Java)), was placed in charge of the Commission Enquiring into Declining Welfare in Java and Madura.[67] Begun on 1 July 1904, the inquiry produced thirty reports. One volume was dedicated to the position of women, ‘De Verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw’ (‘Lifting up the Native Woman’); it was one of the few instances of the colonial government explicitly including women in their policies.[68] Steinmetz was adamant that the volume should also contain essays by indigenous women themselves, and after a great deal of difficulty and effort, this is what happened. In the end, nine women wrote a contribution to the volume: almost all of these belonged to the aristocracy (priyayi) with only two exceptions, one of whom was Djarisah who once more found herself in a minority role, again illustrating her position at the time.

Djarisah enthusiastically seized this opportunity to put her ideas to paper and in June 1914, she filled seven pages with her thoughts. Her contribution to the report started off: ‘most women first need to have gained experience before they can shake off their prudishness, in order to express their opinion in public.’[69] This did not apply to her, of course; after all, she had already gained experience at Madju Kemuljan.

Her essay shows a jumble of ideas. Opinions that she held as a board member with Madju Kemuljan recur again, such as her warning to young women not to listen to the sweet little words that men whisper to them.[70] Women were receptive to such words, she argued, because they had received (little or) no education. Hence her exhortation that women should complete a vocational training programme so as to be economically independent and not run the risk of falling into the hands of a wicked man. Yet women were also advised to do a kind of home economics class to prepare them for motherhood: to learn about hygiene and parenting.[71] Djarisah’s expectations of women were sky-high: should unexpected woes befall their household, a proper housewife was also expected to manage and comfort her husband.[72] But women were not exclusively to be held accountable for all that was wrong: their parents carried responsibility as well, in Djarisah’s eyes: some fathers refused their daughters permission to train for a line of work. And parents sometimes matched their daughter up with a man she did not care for; in desperation, the daughter might then stray from the straight and narrow, into prostitution, in short.[73]

In her contribution to the volume, Djarisah made the most of the opportunity to express her views on the midwifery training and on midwifery as a profession. She did not hesitate to speak out against a proposal made by J.H. Abendanon, a very senior civil servant who was director of the Department for Education, Worship and Industry and de facto minister of education in the colony. Abendanon meant to introduce a short training programme for midwives, but in Djarisah’s opinion, midwives would not obtain sufficient professional knowledge and know-how under his proposal, and would thus put women in childbirth at risk.[74] Instead, she proposed a one-year course for assistant-midwives. Once they had completed this programme, they would return to their own desa (village) to practise among their fellow villagers. Pregnant desa women would be obliged to call in the assistant-midwife as soon as they went into labour. ‘And where the Native is known for his indolence, there, in my opinion, should a light penalty clause be introduced,’ Djarisah recommended.[75] Her statement recalls the view of her tutor, H.B. van Buuren. If any complications arose during the birth, assistance should be sought from a certificated midwife, like herself. In such cases, the government was to subsidise the woman’s transport to the midwife’s house. Steinmetz deemed it necessary to ask the head of the Medical Service for a reaction to these ideas; he partly agreed with Djarisah. However, he was against the idea of forcing desa women to call in a qualified midwife as this would meet with resistance, and imposing a penalty would turn the indigenous population against Western medicine.[76] And where Djarisah saw the dukun bayi’s poor obstetric care as the great evil, which had already cost so many lives, he remarked that first, it had to be established how many lives had, in actual fact, been lost and whether this number was indeed greater than for those who perished from diseases like dysentery or malaria.[77] A discussion was being waged at the time within the Medical Service as to which should be prioritised: obstetrics or general healthcare.[78]

Djarisah also addressed the matter of the relations between men and women. With her usual consistency, she saw good education as the panacea. Girls ought not to marry before their sixteenth birthday, when they had received sufficient education. They should be able to choose their husbands themselves. This would also root out the practice of child marriage.[79] Prostitution and adultery were attributable, according to Djarisah, to the fact that women were given no education. Poverty drove them to prostitution and they committed adultery because they were unable to curb their passions and wickedness.[80] She denounced concubinage but the system of co-wives, the so-called selir system, found even less favour in her eyes.[81] She thus levelled more criticism at her fellow country men, often the upper classes in the Princely States (Vorstenlanden), who had one or more concubines (selir), than at the European men who lived with an indigenous woman (nyai). The highlight of her piece was her proposal to abolish polygamy. Djarisah appreciated that she could hardly blame men for the practice since the Koran not just allowed but even promoted polygamy. She was aware that as a Christian she was treading on thin ice here. Even so, she wished to express her thoughts freely: in his time, Mohammed had advised his followers to take several wives in order to increase the number of his acolytes. Yet any right-minded person recognised that this was no longer necessary. ‘That is why I repeat: polygamy out, if necessary through an adjustment to the Koran prescript concerned!’[82]

In her article we find a rousing appeal to men’s desire for progress:

If the Javanese people really aspire to progress, the men will undeniably require the help of women. But then, they need to be freed from all kinds of impediments in the general race (of life). In short, and to the point, I want to give men this choice: progress with free women or continued darkness with slaves for wives? If they want the former, then outdated religious ideas must not be spared.[83]

However promising this parting shot in the Declining Welfare report may sound, it would prove to mark the end of the brief but brilliant career of Djarisah, whose life would continue for over 50 years.

After her heyday

Ideally, every biography contains a passage about the personal life of the person concerned. Unfortunately, sources for Djarisah’s life are extremely scarce. It is known that her father and mother were Titoes Redjalan and Martinah, and Djarisah was the youngest of their eleven children.[84] When Djarisah left for the Netherlands in October 1912 for additional training, she emphasised that she did so without her parents’ knowledge.[85] It is therefore likely that her parents were then still living in Mojowarno. If they had also lived in Bandung, they would surely have noticed their daughter’s absence.

The warning Djarisah sounded in her report to young women that they should not heed the sweet words men whispered to them may have been based on her own experiences. For all her being an independent woman economically, even Djarisah fell into the hands of a fraudster. At the end of 1910 Djarisah met a handsome, indigenous man in Bandung, who fooled her into believing that he had a good job in Surabaya (East Java). He wanted to marry her. Having lived with him for a month, Djarisah decided to move with him to Surabaya, selling all her furniture.[86] Once there, he turned out to be a swindler and she was left with enormous debts (ƒ 6000, nowadays ca € 70,000).[87] She returned to Bandung to pick up her old profession again.[88] The Indies press went to town on the story and published an extensive version, entitled ‘Damsel desperate for a husband fooled’.[89] Djarisah may have been a widow at the time; a newspaper article describes her as ‘little widow’.[90] Since there were no civil registry records for Indonesians, it is impossible to know.

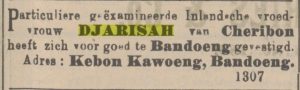

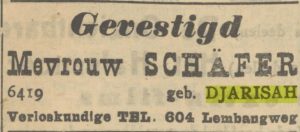

A few years later, in 1916, Djarisah married the Dutch man Karel Huybert Schäfer (1862-1937), a chief clerk with the State Railways.[91] The marriage remained childless.[92] On her marriage, Djarisah received Dutch citizenship. When her husband retired, the couple left for the Netherlands, where they remained from February 1922 to late July 1923. Djarisah continued to work as a midwife for some years after her marriage but now under her husband’s name, as Mrs Schäfer neé Djarisah (see Figure 4).[93] Although it appears she stopped advertising her services after 1924; she was still listed in the 1929 Newcomers to Bandung guide as accoucheuse.[94] Her husband passed away in 1937 and upon his death, Djarisah received a pension.

Djarisah’s view on colonialism

European institutions played a decisive role in her life. Djarisah belonged to the small minority of Indonesians who were Christians, by contrast with the vast majority who were Muslims. It is to this particular background that she owed her education and training, and her ranking among the 0.1% indigenous women who had received some form of education, meaning Western education. She was trained to be a midwife by a Dutch physician and primarily tended to European and Eurasian pregnant women upon her certification. Her European training also influenced her thinking and views: she would never view a dukun bayi as a colleague; shared the European doctors’ opinion of their (lack of) expertise. Upon her marriage to a European man, she received Dutch nationality, which she retained after independence was declared. For all that, Djarisah continued to wear sarung and kebaya. In this respect, then, she was like any indigenous woman; most women in the nationalist organisations similarly opted for traditional garb,[100] in contrast to the men in these organisations and the male elite, who preferred Western-style dress.[101]

Contemporary proponents of the Ethical Policy must have seen her as living proof that Indonesians could indeed be equal to Europeans, provided they were well educated. The Ethical Policy took association for its starting point: the Dutch East Indies was permitted to develop into a self-sufficient region within the Kingdom of the Netherlands provided it sought Dutch guidance and adopted a Western-style development model.[102] The point is illustrated by Steinmetz, chairman of the Welfare Commission, as he describes a visit to Djarisah:

It was on an evening, that I wished to see her, she had not returned home yet and I therefore had to wait a while, a good opportunity to observe her private setting more closely. A neat, simple house, with rattan furniture in the front veranda, and a desk on which books and correspondence are laid out in the inside veranda, in short, an interior, where I did not feel a stranger, where a mood of association enveloped me; I was proud that a Native woman had managed to set up such an independent line of business for herself under our government.[103]

On the one hand, his description flatters Djarisah; on the other, it is very patronising: what she has brought about is foremost the accomplishment of colonial policy.

Nowhere does Djarisah direct criticism at the Netherlands and/or colonialism. She is, however, critical of her compatriots: ‘One must not be satisfied too soon! The Natives often have a tendency to be easily content, and that is why their progress is so slow. They need to be roused to everything!’[104]

Concluding remarks

Djarisah was a Javanese woman who led a for her times remarkable life as an indigenous woman with paid work who, moreover, entered the public domain on a regular basis. Her life path was unusual and this must surely have given rise to problems. In her own words: ‘As a Native woman, I have initially had to fight a titanic struggle to gain the independent livelihood that I now have.’[105] The press too noticed that she had managed to build up a life of her own after a long battle with ancient Javanese traditions.[106] She freed herself from the impediments that her gender and origin imposed. Her strong character helped her in this bid for freedom. Shortly after the debacle with the swindler, she left for the Netherlands to gain a certificate. Her stay in the Netherlands not only obtained her a Dutch diploma, it undoubtedly also provided her with the experience of being treated very differently by the Dutch than she usually was on Java. A lack of sources unfortunately makes it impossible to assess how her stay in the Netherlands affected her self-confidence, but her reaction to the afore-mentioned train incident may well speak volumes.

Djarisah’s life path was largely a solitary one, as she was all too aware: ‘I am all on my own’.[107] She was an against-the-grain outsider in all respects: as a Christian, she belonged to a small minority; as a midwife, she worked on her own, without any direct colleagues; she had acquired a certain position in society on account of her work and she rubbed shoulders with Indonesians from the upper classes (priyayi) as well as with Europeans, despite being a Javanese woman from humble, ordinary origins. Except for the brief period of her membership of the board of Madju Kemuljan, Djarisah’s was always a solo effort. To my knowledge, she never joined any of the many nationalist organisations or any of the women’s organisations; it was especially during the first decades of the twentieth century that these mushroomed. The oldest women’s organisation, Putri Mardika (Independent Woman), founded in 1912, was opposed to such practices as child marriage and polygamy,[108] two customs that also raised revulsion in Djarisah, as we saw earlier. Djarisah sat on the board of Madju Kemuljan with Raden Dewi Sartica, who also wrote an article for the Declining Welfare Report. Obviously, her contribution dealt with education – she was, after all, the headmistress of the girls’ school she had founded in Bandung; in addition, she also addressed the issue of child marriage and polygamy, which she termed a gangrene in society.[109] Yet it does not seem as if the women were an inspiration to each other. Neither is there any evidence of Djarisah being aware of the existence of her famous contemporary, Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879-1904), who fought for the education of women, the promotion of monogamy and a re-evaluation of Javanese culture.[110] In other words, her and Djarisah’s battlefields largely overlapped. This raises the question who Djarisah was influenced by, what she drew inspiration and power from. She may have derived her commitment and drive from her religious beliefs: her death notice says that she ‘fell asleep in her Lord Jesus Christ, Whom she served all her life in her own manner’.[111]

Women, whether European or non-European, have long been neglected by historical research. This has certainly changed with the second feminist wave and the emergence of women’s history, subsequently termed gender history. Djarisah is extraordinary in the sense that she, an ordinary Javanese woman from the colonial era, can not only be written about but also wrote herself. Her publications constitute unique source material. Notwithstanding these sources, however, many questions about her and her life remain unanswered. These include, for instance, questions about her choice to work in West Java (Cirebon, and then Bandung) while her origins were in East Java.

Djarisah practised her profession for about thirty years; she was a social activist for a very short period of that time – for just over two years. Her views on the position of women coincided with those held by indigenous women’s organisations, which she, however, never joined. And because she did not join a nationalist organisation either, she was never given the merit, once Indonesia had obtained independence, that her views and activities should have accorded her.

References

[1] Anonymous, ‘De strijd tegen de prostitutie in ernst begonnen’, De Expres, 1 May 1914.

[2] Elsbeth Locher-Scholten argues that a number of end dates may be used for the Ethical Policy: 1910, 1912, 1920, 1927, 1930, 1942. She terms the policy as of 1920 a conservative ethical policy. I have accordingly opted for that year as the end date of the Ethical Policy. Elsbeth Locher-Scholten, Ethiek in fragmenten (Utrecht: HES Publishers, 1981), 176, 203.

[3] Some notes on terms used in this article: The terms ‘Indonesians’ and ‘indigenous population’ are used synonymously. The background setting for article is Java, part of (the Indies archipelago), itself part of the Dutch East Indies. Wherever the term ‘Indies’ is used in the text, it refers to the Dutch East Indies, not to another colony such as the Dutch West Indies.

[4] I use modern spelling to refer to place names, i.e. Mojowarno and Bandung rather than Modjowarno and Bandoeng. Batavia remains Batavia.

[5] It was the most important Christian community on Java, Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch-Indië (’s-Gravenhage: Nijhoff, Leiden: Brill, 1918) vol 2, 760.

[6] S. Coolsma, De zendingseeuw voor Nederlandsch Oost-Indië (Utrecht: Breijer, 1901), 230-6.

[7] Upon her arrival in the Netherlands Djarisah was recorded as not having attended any school (Report to the Medical Adviser of the Ministry of Social Affairs on Schäfer-Djarisah, National Archives 2.27.09, inv. no 4834 [hereafter Report to the Medical Adviser]). I query the correctness of this as the ability to read and write was a prerequisite for admission to the midwifery training. Over time, she may increasingly have considered herself a self-made woman, for the very reason that she always worked on her own.

[8] Verslag der handelingen van de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal 1907-8; part 8, Koloniaal Verslag 1907, appendix A.

[9] During the colonial era, it was the women from the higher social classes (priyayi) who profited most from the growing opportunities for education; all the work in the context of educational opportunities still had to be done for women from the lower classes, Cora Vreede-de Stuers, The Indonesian Woman: struggles and achievements (Paris/The Hague: Mouton, 1960) 70-1.

[10] H.E. Steinmetz, Onderzoek naar de mindere welvaart der Inlandsche bevolking op Java en Madoera.IXb3. Verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw; part VII van ’t overzicht van enz de economie van de desa (Batavia: Papyrus, 1914), 39.

[11] The mission had a few teacher training colleges and three technical schools, Sita van Bemmelen, ‘Enkele aspecten van het onderwijs aan Indonesische meisjes 1900-1940’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, Utrecht University, 1982), 9.

[12] For more information, see Liesbeth Hesselink, Healers on the Colonial Market: Native doctors and midwives in the Dutch East Indies (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2011).

[13] Charlotte Borggreve, Gouvernementsarts in Indië (Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2007): 60; thanks to the author for allowing me the use of this photograph.

[14] Hesselink, Healers on the Colonial Market, 232-5.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Soerabaiasch Handelsblad, 1 February 1899. In 1914 a mere eleven women had passed this exam. Steinmetz, Verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw, 86.

[17] Verslag der handelingen van de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal 1901-2, part 7. Koloniaal Verslag 1901, appendix T.

[18] Soerabaiasch Handelsblad, 12 June 1900.

[19] H B van Buuren, ‘Een jaar later’ (offprint from Nederlandsch Tijdschrift voor Verloskunde en Gynaecologie, 1900).

[20] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’, in Steinmetz, Verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw, 14*-20*, 18*.

[21] Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1904, 201 mentions three indigenous midwives in Cirebon; two of whom, including Djarisah, received a government allowance. Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1906, 646 mentions the same three indigenous women as in 1904, but now none of them receives an allowance; Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1907, 745 lists Djarisah as a midwife stationed in Cirebon.

[22] H.B. Buuren, Het verloskundig vraagstuk voor Nederlandsch-Indië naar aanleiding van het rapport der commissie tot voorbereiding eener reorganisatie van den burgerlijken geneeskundigen dienst aldaar (Amsterdam: Scheltema& Holkema, 1909), 36 and 58-67.

[23] De Preanger-Bode, 15 October 1907. Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië 1908, 779 lists four indigenous midwives in Bandung, including Djarisah, none of whom received an allowance. The Regeringsalmanak voor Nederlandsch Indië 1916, vol 2, 407 records Djarisah as one of the four midwives in the column ‘Private physicians, surgeons, obstetricians and dentists’ in Bandung; the other three are married and have European names, either their own or their husband’s.

[24] De Preanger-Bode, 15 October 1907.

[25] Anonymous, ‘Een trouwlustig vrouwtje gefopt’, De Preanger-Bode, 17 February 1911 (copied in Het Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 18 February 1911).

[26] Anonymous, ‘Openbare vergadering “Madjoe Kemoeljan”’, De Preanger-Bode, 1 May 1914.

[27] Anonymous, ‘Ontrouwe’, De Preanger-Bode, 1 June 1908. Anon., ‘Een trouwlustig vrouwtje gefopt’.

[28] In, among others, De Expres, 6, 9, 13 May 1914. From 1914 Djarisah stated in advertisements that she was able to put up women who had recently given birth, De Expres, 12, 13 March and 1, 4, 15, 17, 18, 25 April 1914.

[29] Djarisah, ‘Typeerende manieren’, De Expres, 19 December 1913.

[30] De Preanger-Bode, 13 June 1908; Het Nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 27 December 1913; De Preanger-Bode, 29 December 1913; De nieuwe Vorstenlanden, 29 December 1913; Algemeen Handelsblad, 26 January 1914; Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 29 January 1915; Het Nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 29 January 1915; De Preanger-Bode, 30 January 1915; De Avondpost, 8 March 1915; Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 28 January 1916.

[31] Observer, ‘Ingezonden’, De Preanger-Bode, 9 March 1915 (and cf. a letter to the editors on 6 March 1915).

[32] Anonymous, ‘Een kliniek in uitzicht’, De Preanger-Bode, 11 December 1915.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Anonymous, ‘Naar Holland’, De Preanger-Bode, 10 October 1912 and 12 November 1923; Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’, 19*. In 1958 Djarisah was recorded as having worked fifteen days in doctor De Snoo’s clinic; she did not mention a Dutch certificate, Report of the Medical Adviser.

[35] Advertisements in, among other papers, De Expres, 20, 29 September 1913.

[36] In ‘Lijst van abonnees’, Tijdschrift voor praktische verloskunde, 15 May 1914 (vol 18 no 2) Miss Djarisah is the only midwife from the Indies. In ‘Lijst met abonnees’, Tijdschrift voor praktische verloskunde, 1 June 1922 (vol 26, no 3) she is listed as Mrs Schäfer-Djarisah and as having taken out a subscription, as had five other midwives in the Indies, including Mrs Roelofs-Djasminah in Yogyakarta; like Djarisah, she had been trained by Van Buuren.

[37] Klaas de Snoo (1877-1949) was the director-physician of the Rotterdam midwifery school from 1 January 1907 and a professor in Utrecht from 1929; he worked at the Batavia Medical School for one year in 1937. A special issue of the Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde was dedicated to De Snoo in 1947.

[38] Djarisah, ‘Typeerende manieren’.

[39] A.D., ‘Verkeerde dingen in onze samenleving’, De Expres, 22 December 1913.

[40] Multatuli was the pseudonym of Eduard Douwes Dekker (1820-87). His novel, Max Havelaar (1860), sharply criticised the colonial policy and was itself both criticised as well as admired. It became a bestseller, which has been translated into numerous languages; D., ‘Nog eens parabatavisme’, De Expres, 13 May 1914.

[41] Mevrouw A.L., ‘Nogmaals de Javaan en de internationale kleederdracht’, De Expres, 22 July 1914.

[42] Ulbe Bosma and Remco Raben, De oude Indische wereld 1500-1920 (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2003), 311.

[43] Abdoel Rivai, ‘Holland, de Inlanders en nog iets’, Koloniaal Weekblad, 3 May 1906, 6-18; Hesselink, Healers on the Colonial Market, 202-3.

[44] Elsbeth Locher-Scholten, ‘Familie en liefde: Europese mannen en Indonesische vrouwen’, in Vertrouwd en vreemd: ontmoetingen tussen Nederland, Indië en Indonesië ed. by Esther Captain, Marieke Hellevoort en Marian van der Klein (Hilversum: Verloren, 2000), 45-51.

[45] Ibid., 46.

[46] Founded in 1892 and 1893, respectively.

[47] Elsbeth Locher-Scholten, Women and the Colonial State: essays on gender and modernity in the Netherlands Indies 1900-1942 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2000), 19.

[48] Locher-Scholten, ‘Familie en liefde’, 47.

[49] Raden is a noble title used within the Indonesian nobility.

[50] Wibisana, ‘Associatie van Oost en West op het gebied der bestrijding van de ontucht’, De Expres, 23 February 1914; De nieuwe Vorstenlanden, 24 February 1914; Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 25 February 1914; De Sumatra Post, 27 February 1914.

[51] Anonymous, ‘Bestrijding van prostitutie’, De Expres, 21 March 1914; Anonymous, ‘Madjoe Kemoeljan’, De Preanger-Bode, 22 March 1914; ‘Vereeniging tegen de ontucht’, Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 27 March 1914.

[52] Anon., ‘Naar Holland’.

[53] Anon., ‘Openbare vergadering “Madjoe Kemoeljan””; Anon., ‘De strijd tegen de prostitutie in ernst begonnen’; Anonymous, ‘Vereeniging “Madjoe Kemoeljan”, Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 5 May 1914; De Sumatra Post, 11 May 1914.

[54] Anon., ‘De strijd tegen de prostitutie in ernst begonnen’.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’, 14*; italics added by Djarisah.

[57] Anon., ‘Bestrijding der prostitutie’; Anon., ‘Vereeniging tegen de ontucht’; Anon., ‘Openbare vergadering “Madjoe Kemoeljan”’; Anon., ‘De strijd tegen de prostitutie in ernst begonnen’; Anon., ‘Vereeniging “Madjoe Kemoeljan”’; Anonymous, ‘Bestrijding der prostitutie’, De Nieuwe Courant, 28 May 1914 (also in Het Vaderland, 30 May 1914); De Inheemsche Vrouwenbeweging in Nederlandsch-Indië en het aandeel daarin van het Inheemsche meisje (Batavia: Landsdrukkerij, 1912), 7; M. Lindenborn, ‘Verheffing van de inlandsche vrouw’, Stemmen voor waarheid en vrede, Evangelisch tijdschrift voor de Protestantsche kerken (Utrecht: Kemink) 1915 (vol 52), 993-1017, 1002.

[58] Levenskracht, maandblad voor reiner leven, 8/7 (1914), 156.

[59] Anonymous, ‘Strijd tegen handel in vrouwen’, De Expres, 14 July 1914; Anonymous, ‘Madjoe Kemoeljan’, De Preanger-Bode, 4 September 1914.

[60] Anonymous, ‘Madjoe Kemoeljan’, De Preanger-Bode, 16 June 1915.

[61] Anonymous, ‘Bestuursvergadering “Madjoe Kemoeljan”’, De Preanger-Bode, 10 May 1915; Anonymous, ‘Opleiding Inlandsche vroedvrouwen te Bandoeng’, Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 12 May 1915.

[62] Anon., ‘Madjoe Kemoeljan’.

[63] He made it known via the newspaper, De Nieuwe Vorstenlanden, 23 May 1916, that his move to Cirebon was the actual reason but he had also been absent from the meeting in 1915.

[64] De Preangerbode, 4 December 1917.

[65] H.W. van den Doel, Het rijk van Insulinde: opkomst en ondergang van een Nederlandse kolonie (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 1996), 157.

[66] Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch-Indië vol 4, 752.

[67] Herman Eduard Steinmetz (Surabaya 1850-1928), Resident van Pekalongan (Central Java).

[68] Steinmetz, Onderzoek; Anon., ‘Een nakomer’, Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 4 February 1915. I suspect, incidentally, that this was especially due to Steinmetz’s influence; he was intensively involved with the report’s content, and was well acquainted with Dutch feminism.

[69] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’, 14*.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Ibid., 15*.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Ibid. 16*.

[74] Hesselink, Healers on the Colonial Market, 247.

[75] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’,18*.

[76] Ibid., 18* note 2.

[77] Ibid., 19* note 1.

[78] Hesselink, Healers on the Colonial Market, 242-3.

[79] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’,18*.

[80] Ibid., 16*.

[81] Ibid., 17*.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie (Centre for Family History), Nederland’s Patriciaat (’s-Gravenhage: De residentie), vol 54, 1968, 200; Report to the Medical Adviser.

[85] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’, 19*.

[86] De Preanger-Bode, 8 August 1910; 9, 10, 12, 13 and 14 December 1910.

[87] De Preanger-Bode, 17 February 1911. This refers to present purchasing power, see www.iisg.amsterdam accessed 10 July 2022.

[88] De Expres, 5 March 1912.

[89] Anon., ‘Een trouwlustig vrouwtje gefopt’.

[90] Ibid. The fact that she lived together with this man for a year might imply that she was a widow; cohabitation without marriage would have been taboo for an unmarried young woman.

[91] Anon., ‘Hoofdcommies bij de Staatsspoorwegen op Java’, Het Vaderland, 18 October 1911; Het Nieuws van den dag, 29 August 1916; Centraal Bureau, Nederland’s Patriciaat, 200.

[92] In 1958 Djarisah, seventy-eight at the time, was recorded as having had an abortion at one time. This experience must have stayed with her all through her life, Report of the Medical Adviser.

[93] De Preanger-Bode, 28 January 1918; 4, 11, 18 February 1918, among other papers.

[94] I managed to find sixty-four advertisements on Delpher; the last one dates from 27 September 1924. Gids voor den nieuw-aangekomenen te Bandoeng (s.n.: Bandoeng, 1929), 67.

[95] De Preanger-Bode, 4 March 1918.

[96] According to De Nederlandsche soroptimist 13/2 (1959), 11, K.H. Schäfer-Djarisah is a resident of the Bejaardencentrum voor Gerepatrieerden (Care Home for Elderly Repatriates), Dennenrust in Renkum.

[97] De Telegraaf, 19 April 1971; Het Parool, 20 April 1971. Mrs A. Jansz may have been the director of the last care home she was in; she could also be a relative of P. Jansz, a missionary in the Indies, with whom Djarisah may have had contact through the church.

[98] My efforts to come into contact with her husband’s relatives have been to no avail.

[99] Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie (Centre for Family History), Oud-Paspoortarchief Nederlands-Indië.

[100] Steinmetz, Verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw, 120-1. The editor of Putri Mardika in Mevrouw A.L., ‘Nogmaals de Javaan’.

[101] Hesselink, Healers on the Colonial Market, 200-1.

[102] L. Jeroen Touwen, ‘Paternalisme en protest: Ethische politiek en nationalisme in Nederlands Indië, 1900-1942’, Leidschrift 15/3 (December 2000), 67-94. The idea of assimilation goes beyond this as it requires the indigenous population to adopt and completely incorporate Dutch culture and civilisation.

[103] Steinmetz, Verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw, 49.

[104] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’, 15*.

[105] Ibid., 16*.

[106] De Preanger-Bode, 12 November 1923.

[107] Djarisah, ‘Losse gedachten’, 16*.

[108] In their weekly Putri Mardika, as of 1915; Surat kabar memperhatikan pihak perempuan bumi putra di Indonesia, Vreede-de Stuers, The Indonesian Woman, 62.

[109] Raden Dewi Sartica, ‘De Inlandsche vrouw’, in Steinmetz, Verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw, 21*-5*, 22*.

[110] Locher-Scholten, Women and the Colonial State, 21.

[111] De Telegraaf, 19 April 1971; the medical adviser’s report similarly states that she was very religious.