| Sharon Whiting, University of Manchester |

The UKAHN Bulletin |

| Volume 10 (1) 2022 | |

Introduction

This article introduces a project that has both personal and professional motivations. As a registered nurse with thirty-five years’ experience working in the field of adult intensive care, as bedside nurse and educator, I am an advocate for critical care nursing and raising the profile of critical care nurses. Increasingly, I have come to understand that central to this is the need to understand and disseminate the history of critical care nursing. This article is based on a part-time PhD project which began in 2017. It presents the progress so far of work that will contribute to a history of critical care nursing; it also introduces a place and some people central to the work together with some early findings. Each will inform a narrative which aims to explain the fundamental role of nurses in the founding of intensive care units (ICU) and their wider contribution to the delivery of critical care medicine in English NHS hospitals during the twentieth century, as well as contributing to histories of nursing and women’s work. Reading this account might encourage other non-historian nurses to delve into other areas of nursing history which resonate with them and their experiences.

In 2015 a senior colleague retired. Her retirement created a personal ripple effect I did not realise would impact my future path so profoundly. She had worked at North Manchester General Hospital (NMGH) as a critical care nurse for forty years. In a room of people toasting her achievements and wistfully caught in a moment of reflection I found myself mourning the loss her retirement represented. This was a loss not just to those present, but loss in terms of a place and time in nursing and medicine when English intensive care evolved. I was left wondering who would capture it.

The reading began. Early searches quickly identified international work authored by nurse historians detailing ‘their’ history of critical care nursing, and reinforced the gap in the history of British critical care from a nurse’s perspective, which is largely unrecorded.[1] Others have acknowledged this too. Graham Haynes, one of four nurse contributors to a Witness Wellcome Seminar exploring the history of British intensive care, suggested: ‘If you did a nursing/ITU seminar, you’d get another perspective and more nurses attending’.[2]

The Project

My study will use both oral history and archival research to collect primary evidence, which will offer insights into the working lives of critical care nurses in England, rich in detail and framed within wider political and cultural context. To date thirteen oral history interviews have been recorded, including with ten female and three male retired nurses.[3] Early in the sampling process it was envisaged that ten to fifteen participants would be a manageable number, and which will produce usable data for analysis. All participants were nurses on the ICU at NMGH for a time between 1967 and 2000. These dates are significant because they encompass the year the first unit opened and the last major NHS reorganisation of English critical care services.[4] Six of the thirteen interviews were conducted online (via Skype) due to 2020 Covid-19 pandemic travel and meeting restrictions. The British Library Oral History Team provide valuable guidance for remote interviews.[5]

While it has been possible to undertake oral history interviews remotely, the closure of archives due to the Covid-19 pandemic has severely restricted opportunities to consult primary material. This aspect of the research has only recently been initiated, and visits are now planned to the Wellcome Collection Library, National Archives at Kew, the British Library, and British Film Institute Archives in late 2022.

Access to local archives, however, has been easier to achieve. Manchester’s Central and University libraries have provided valuable primary sources including minutes of hospital meetings and nursing journals from the 1960s, while interview participants’ private collections have provided many previously unseen personal photographs.[6] These promise to enhance the narrative and create a unique opportunity for analysis, illustrating local developments and innovation as the ICU evolved at NMGH. A selection is included in this report with the permission of all copyright holders.

The emphasis on representing the ‘English’ view of this history has raised questions and created debate with my academic supervisors. Whilst the descriptor ‘English’ fits the geography of the unit at NMGH, it would be an omission not to examine the wider British context within which other early units opened and critical care nursing evolved. It is envisaged that access to national collections and associated archival research will increase the limited number of primary sources collected which reference the development of ICU in other urban clinical centres across the UK. Extending the analysis will lead to a final narrative that is stronger and more representative of the wider British story.

The Development of Critical Care Nursing at North Manchester General Hospital

The choice of NMGH for this project is a reflection of the vision, innovation, and early investment the hospital placed on intensive care. My long professional nursing affiliation with the hospital and the ICU make the choice of it as the focus of my study one of personal luck (serendipity) and pragmatism. The hospital has a long history of serving the community of Crumpsall, a suburb to the north-east of Manchester. Similar to many English district general hospitals it was founded as a Victorian institution caring for the poor, opening in 1876 as a workhouse infirmary (Figure 1) which cared for the sick incumbents of the adjacent workhouse.[7] The infirmary became Crumpsall Hospital when the workhouse closed, was assimilated into the NHS in 1948 and continually adapted to local and national reorganisations, becoming NMGH in 1974.[8] In 2021 the hospital joined Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) with the creation of the Single Hospital Service for Manchester.[9]

Another much cited impetus for the adoption of intensive care was the concept of ‘progressive patient care’ advocated by US policy. This was a strategy to save money by organising hospitals and their nursing into three groups differentiated by patient dependency, the sickest being ‘intensive care’.[15] The US project directly influenced the decisions of managers at NMGH; minutes from meetings of the hospital Medical Committee in 1965 directly cite ‘progressive patient care’ supporting a local scoping exercise for a ten-bed unit.[16] Notably, organising nursing was seen as central to this ‘progressive’ incentive, even though a century earlier Florence Nightingale had argued that the sickest patients should be a cohort together and in direct sight of nurses.[17] This reminds us that from the beginning, nursing was pivotal to the success of intensive care.

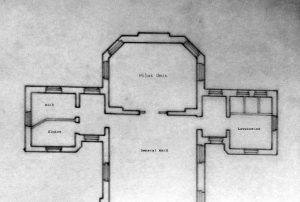

NMGH was an early adopter of general intensive care in Manchester. The first ‘pilot-unit’ at NMGH opened in 1967 after the hospital management committee agreed to provide £316 (equivalent to £5,374 by 2022 estimations) to build a partition wall and alter a disused day-room to accommodate a two-bed ICU unit. Approval was considered ‘of considerable urgency’ given that ‘The Hospital Medical Staff Committee, with the support of Matron and the Medical Superintendent’ had already supported the development.[18] Built at the end of an existing Nightingale-style ward the space was just large enough to contain two beds and the limited technological paraphernalia the hospital held to monitor and treat critically ill patients (Figures 2a, 2b, 3).

The private papers of founding clinician Dr David Morrison and minutes from the hospital committee meetings reveal how nurses were recruited to staff the unit. The hospital matrons were central players in selecting staff for this new team, and it would appear they chose those they deemed most ‘suitable’ from the existing pool of hospital nurses.[19] Interviewees note that two matrons in particular were especially influential: Mrs Isabel Comber-Higgs (1953-1967) and her successor Miss Audrey Monks (1967-1972). As the two-bed pilot unit was being planned, Comber-Higgs’s contribution is recorded in minutes of the management committee that she was able to ‘secure eight trained nurses’ to staff it.[20] The same minute reports how she supported the specialist education of these eight and agreed that ‘two at a time would undertake intensive care nurse training’ returning to ‘form the nucleus of nursing staff for the more permanent unit’.[21] The investment and support of the matrons for this fledgling enterprise reflects a nursing management with a vision for extending future nursing practice at NMGH.

Suitability is clearly a subjective criterion for selection, however there were common traits and skills matrons witnessed in the nurses who they put forward to join the pilot unit. Interviewee Patricia Macartney demonstrated this abundantly. She was directed to work in the pilot unit on its opening in 1967, and her interview is laced with examples demonstrating why Comber-Higgs might have identified her (and nurses like her) as ‘suitable’ for working in the new ICU. Macartney had grown up near Preston and moved to NMGH as an eighteen-year-old in 1964 to train at the school of nursing. As a student she recalls multiple training allocations to the neurosurgical ward: ‘I did neurology and neurosurgery. I did a lot of neurosurgery … nights for six weeks … and then two spells of days’.[22] This was an area where her aptitude in dealing with very sick and highly dependent patients would have been noted by matrons. Qualifying in 1967 and after another short period in neurosurgery as a staff nurse, Macartney moved to a medical ward where, according to her interview she first encountered the new specialism, ‘Well, intensive care arrived on that ward, and that’s why I did it’, she recalled.[23] This modesty fails to acknowledge her direct contribution to the development of critical care nursing skills at NMGH. It similarly fails to demonstrate how or why she was one nurse on the medical ward who would readily volunteer to ‘special’ patients who needed respirator support. ‘Specialing’ meant nursing sick patients one-to-one, and the arrival of the hospital’s first respiratory support equipment (early ventilators) meant overseeing these too. Macartney recalled having ‘from Dave Morrison… a crash course on the respirator’ and described how there would ‘be a nurse there at all times, doing the recordings and things.’[24] Nurses who demonstrated a talent and enthusiasm for working closely with doctors to care for such challenging sick patients and embracing the new technology would no doubt have attracted the matrons’ attention. Hence, Macartney was invited to work on the pilot unit when it opened in 1967, and one of the first NMGH nurses to be supported to gain a specialist nursing qualification in intensive care nursing. She was seconded to Whiston Hospital, near Liverpool to an existing general ICU that had developed an early training course for nurses. On her return to NMGH in 1970 she was promoted to sister. Macartney would become lead nurse for ICU at NMGH, a position she held until 1980 when she left to become a community nurse.

Isabel Comber-Higgs retired in 1967, meaning her successor Audrey Monks had more influence on recruitment to the second (permanent) unit. A history of the workhouse and hospital at Crumpsall describes Monks as: ‘especially involved in the setting up of the intensive care unit’.[25] Interviewee Dianne McCann reflected on Monks’s specific role in recruiting nurses to this second unit.[26] McCann, who trained at NMGH recounted how, on completion of her initial nurse training and subsequent registration in 1970, Monks discussed with her where she would want to work. McCann had wanted acute medicine, but there were no vacancies and was guided toward ICU with the comment: ‘There’s a job coming on ICU, if you want it?… Just do it for six months, you’ll get loads of experience’.[27] McCann had never previously been in the ICU, and mused that matron must have considered her suitable as: ‘a good nurse, a good all-rounder’.[28] McCann would work on the unit as staff nurse and sister until 1986 when she left to become a specialist nurse in infection control at NMGH.

Recruiting nurses to the unit changed as it became more established. The first small number of ICU nurses developed their own views on suitability through clinical experience and post-registration education, and as they became unit sisters gained responsibility for interviewing and employing new nurses to work in ICU at NMGH. At the same time structural changes following the Salmon reforms of 1966 were implemented through 1968 and had a major influence on the Unit’.[29] The old matron roles no longer existed, to be replaced by Principal Nursing Officers. Matron Monks left NMGH as the reforms were implemented, moving in August 1972 to take the role of Principal Nursing Officer at North Staffordshire Hospital.[30] At NMGH the matrons were now also called ‘Nursing Officers’ or more colloquially ‘Number 7s’ (which identified their grading scale under the new system) with changed responsibilities which meant among other things they were no longer responsible for recruitment of nurses into the ICU.[31] This was devolved to the senior sisters on the unit.

The pilot unit’s success secured the Regional Health Board’s support for intensive care at NMGH, and the RHB agreed to build the new, separate, permanent eight-bed ICU which opened in late 1969 (Figures 4, 5 & 6). The unit would expand through the 1970s to accommodate adjacent new additions to the department including a six-bed coronary care unit and three-bed chronic renal dialysis units, and the number of nurses working on the unit grew hugely as a result. The original eight-bed ICU had served a diverse range of critically ill adult patients including those requiring advanced respiratory support, emergency and elective post-surgical care, patients suffering acute medical deterioration, trauma, head-injury, and burns. In the early years the eight beds were frequently occupied by patients following myocardial infarction. It was quickly agreed that these patients, requiring rest, close monitoring and calm convalescence would be better nursed in an area more appropriate to these needs. Hence the coronary care unit was built. The dialysis unit was opened following agreement from the local health authority to meet the growing numbers of renal failure patients in the local community of north-east Manchester; patients would attend on a sessional basis for treatment on an average of three times per week. All the critical care nurses were rotated to staff each of the three areas which ICU covered: intensive care, coronary care, and renal dialysis units. The nurses used their observational, technical, monitoring and patient care skills interchangeably moving between each care area. In the 1990s with intra-hospital departmental reorganisation, each area introduced and retained its own distinct nursing team and the practice of rotating nurses ceased. At this point the qualified nurses were divided between the three areas. This was organised in agreement with the nurse manager for the whole department (now named the critical care unit) and according to personal preference; separately two new senior sisters were employed one each to lead the renal unit and coronary care unit.

As the unit grew more nurses were recruited from outside NMGH. Ellen Chadwick’s story provides one example. Chadwick trained as a nurse in London and after a period working in London, she moved to Sheffield to undertake a post-registration specialist course in general intensive care nursing (known as the ENB 100).[32] On gaining this qualification and hearing there were ‘no jobs’ available in Sheffield, Chadwick who was originally from Manchester, decided to move back to her parents.[33] In 1985 she joined the NMGH ICU unit after answering a job advert posted in the nursing press for a staff nurse position there. During our interview Chadwick recalled how friendly NMGH was and how Dr David Morrison directly influenced her decision to accept the job. She said:

The day I went for my interview I asked to have a look around the unit, and Dave Morrison was there at the time, and he showed me round…and showing me the ambulance and all that sort of thing. And, I think I was just really taken by the fact that he’d taken time out of his day to show me around. So, I got a really, really, good impression of the whole place really, the friendliness of it, you know. It wasn’t just him; it was the people who interviewed me, the people we met on the corridor and stuff like that. I just got a really good feeling about it.[34]

Chadwick would work on ICU at NMGH as staff nurse and sister until 2003 when she moved into Nurse Management in another hospital. Her reminiscences are consistent with others I have collected, demonstrating a close professional collaboration between Morrison and unit nurses. This relationship was central to the unit’s continued success. Morrison had had a long affiliation with NMGH before becoming the hospital intensivist. He had trained at Manchester University, and much of his student experience was at NMGH. Initially, Morrison was a medical generalist with significant technical ability and curiosity. An interest in urology led him to become proficient in dialysis, and set him up for a career in intensive care. He led the unit at NMGH for twenty years. As the lone doctor on the unit Morrison relied greatly on the nurses, their knowledge, skills and intervention. Hugh Chadderton, a male nurse who worked on the unit in the early 1970s as a charge nurse, described the nurses there as ‘Dave’s junior staff’, by which he meant junior medical staff: ‘we didn’t have any junior staff. When we were there, we were his juniors… there were no other medical staff there apart from Dave’.[35] Morrison was influenced, and to a degree mentored by, Dr Eric Sherwood Jones, the founder of the general ICU at Whiston Hospital, in Merseyside that had opened in 1962. The two units had a strong affiliation during the early years of the NMGH unit because of this relationship. Sherwood Jones had disseminated a view that: ‘the first essential for successful general intensive care was a permanent nursing team, specifically trained and giving continuous service’.[36] Whilst working as an anaesthetist in preparation for opening the unit at NMGH Morrison worked at Whiston for a couple of weeks to gain some exposure to the workings of an established ICU. There, he witnessed Sherwood Jones and the Whiston nurses at work and was impressed:

[Sherwood Jones] … created a team of nursing staff of high calibre, who not only worked but played together. The ensemble constituted one of the best therapeutic teams I had ever come across. He had broken all the accepted rules to produce a new and better set of rules altogether. The unit was a unit, and all staff from cleaners to consultant worked in harmony.[37]

This different way of working is something that he aimed to emulate at NMGH’s new ICU, and reminiscences from nurses like Chadwick and others I have interviewed suggest the teamwork philosophy developed by Sherwood Jones and adopted by Morrison had a positive impact on their working lives as nurses. Macartney remembers the general sense on the unit at NMGH of everyone ‘mucking in’ to care for patients. She remembered how after a time Medical Senior House Officers (SHO) would be affiliated to help with patients on the unit:

Everybody got their sleeves rolled up and, when we got our SHO … [t]hey were also coming to terms with a completely different way of working, because our SHOs were medical SHOs – they weren’t surgical, so some of the things they had never done before, so obviously Dave Morrison worked at it, you know, with them and things. But they soon … everybody was expected to be able to do things like the doctors were expected to be able to strip down the ventilators and reset them up, and you know, to prime the dialysis machines; and they learnt to do all that as well as things that they would normally do as a doctor, and so that everybody could turn their hand to it. So, it wasn’t like where the nurse is setting up the trolley for the doctor and everything, they got used to doing it themselves … and even, particularly on nights sometimes you know with people going off to meal breaks and things, a lot of the medical staff would come down, and you know, and sort of spend time down there, so it wouldn’t be unusual to be doing care or moving a patient, and say: ‘Can you just give me a lift here?’ and they would get their sleeves rolled up and do that’.[38]

My analysis of participant interviews and other primary sources will show how this ethos of ‘teamwork’ and flattening of hierarchies contributed to the success of the unit at NMGH having an impact on recruitment and retention. Eight out of the thirteen study participants worked on ICU at NMGH for more than ten years, and only two for less than five years. Such longevity in service could be seen as a symbol of nurse satisfaction that demonstrates the ‘continuous service’ goal was largely achieved.

Difference and innovation were not just limited to ways of working. The ICU looked very different to the Nightingale wards in the rest of the hospital. The permanent ICU internal appearance had a space-age quality (Figures 4 & 7). It was nicknamed ‘the Star Trek unit’ by Sherwood Jones when he first visited it.[39] Within two years of the permanent unit opening nursing staff on the ICU cast off the belts, caps, buckles and dresses worn by nurses elsewhere in NMGH in preference for trousers and tunics; photographs show that doctors and nurses wore the same uniform as early as 1971 (Figure 7). The wider hospital nursing staff would not change female uniform policy to include an option to wear trousers until the 1990s. Innovation extended beyond the unit and into the local community. The ICU had its own ambulance and garage annex, designed by Morrison and funded through charitable contributions (Figure 8). There are examples reported of ambulances being affiliated to coronary care units in Northern Ireland during this era and their provision for retrieval coronary patients was promoted by the World Health Organisation in 1969.[40]

The North Manchester plans for the vehicle went further, it would retrieve and transfer single patients to ICU from other hospitals or attend incidents at the request of the ambulance service. The modern-day paramedic service had yet to be realised, according to the College of Paramedic the earliest example of advanced training for ambulance personnel began in Brighton in 1971. They record how local cardiologist Dr Douglas Chamberlain trained six ambulance men in advanced resuscitation skills to manage cardiac arrest sufferers; local to Brighton it was considered of ‘no proven value’ and shut down by the Department of Health (DH) after five years.[41] The DH did not support a national program of paramedic training in the ambulance service until the 1980s once cost and life-saving potential had started to be evaluated.[42]

Morrison would drive and two or three nurses would escort and assist on scene; a different uniform was worn to provide advanced personal protection for those occasions where risk was heightened (see Figure 9). One interviewee demonstrates why this was necessary: Macartney recalls their attending a serious road traffic collision and a nurse colleague crawling into the wreckage, she said:

…there was always an excitement for major trauma – I know that sounds awful, but it’s so challenging. But some of the positions you found yourself in were a bit, I know one of the girls – She – it was always usually the smallest on site, because you’d get fire fighters and police and they were all big and so they always wanted somebody small to fit in… and one of the girls, she, it was a lorry that had crashed on the motorway, and the driver, they needed somebody in the cab with the driver and it was restricted access and she was quite small so they ‘hoiked’ her up, but it was a bit scary because the fire crews were there and sort of making sure it didn’t burst into flames and things. I remember her coming back and saying ‘God that was a bit hairy.[43]

This Project its Developing Themes, Moving Forwards and Where Next?

As I analyse the nurse interviews, the recurring themes I see are of innovation, adaptation, testing new ways of working, collaboration with multi-disciplinary teams, increased levels of responsibility, the melding of technology with nursing, and changed professional relationships. Furthermore, the nurses’ reminiscences demonstrate a sense of pride; being there at the beginning of something new and exciting. There are other themes too, some reminiscence includes painful memories, stories of patients and care experiences that evoke pain and are difficult to share, of professional challenges and personal demands the work created. My interviewees explain why they were attracted to ICU, how their roles changed and how their nursing adapted to meet the complexity of patient need they encountered. They share strategies they found helped them navigate the demands of the role. One of my hopes is that this narrative could aid critical care nurses of 2022 as they navigate their Covid-19 experience. I envisage that this will be incorporated in later analysis and when this research reaches its concluding stages and is an idea yet to be developed.

Unanticipated findings, to date, include accounts revealing the role, place and contribution of state enrolled nurses and male nurses to ICU at NMGH. Analysis of these nursing experiences require examination of nursing and societal stereotypes, together with discussion of differentiated nursing practice and discrimination. I am challenged to look beyond the confines of the unit and hospital, to examine the wider social, political and economic forces that had an impact on the NHS, hospitals, work and roles of women during this era. Archival work will aid me in this. By accessing primary sources from a wider geographically base, I envisage the parallels and differences found in the development of critical care nursing from other global locations will enrich analysis of this work and act as a different lens through which to view the nursing experience at NMGH.

Personally, it is a privilege to do this work and I thank all my participants for generously sharing their rich, honest and illuminating personal testimony. This article is a snapshot of a work in progress; the aim of the larger project is to record and reveal previously unrecorded aspects of the working lives of critical care nurses in the later years of the twentieth century and to produce one of the first histories of English critical care nursing voiced by the nurses who were there.

References

[1] From the US: Jacqueline Zalumas, Caring in Crisis. An Oral history of Critical Care Nursing (Philadelphia, US: Pennsylvania University Press, 1995); Julie Fairman and Joan E. Lynaugh, Critical Care Nursing – A History (Philadelphia, US: Pennsylvania University Press, 1998). From Australia: Valda Wiles and Kathy Daffurn, There’s a Bird in my Hand a Bear by the Bed – I must be in ICU. The pivotal years of Australian critical care nursing (New South Wales, Australia: Australian College of Critical Care Nurses Ltd, 2002).

[2] Lois A Reynolds, and E (Tilli) M Tansey (eds), History of British Intensive Care, c.1950-c.2000, Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, Vol.42, (London: Queen Mary, University of London, 2011), 38. Only four nurses were named in a list of twenty-eight attending contributors to the seminar.

[3] All interviews were conducted under conditions approved by the University of Manchester ethics committee (UREC). Permission to reproduce material from the interviews was granted by all participants, using their real names, with exception of one who requested their contribution be anonymised. This interviewee has been referred to throughout as Ellen Chadwick.

[4] Department of Health, Comprehensive Critical Care (London: Department of Health, 2000).

[5] British Library, Oral History Team, Advice on remote oral history interviewing during the Covid-19 pandemic (2021) <https://www.ohs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Advice-on-remote-interviewing-during-the-Covid-19-Pandemic-v.70D0A-FINAL.pdf> [accessed 18 July 2022] This link is to Version 7 (8 February 2021) updating version 6 which was posted online on 15 May 2020, and version 5 which was posted online on 4 April 2020. I originally accessed this resource 13 April 2020.

[6] For example: multiple editions of the Nursing Times during the 1960s and 1970s contain images of early ICU. Dr Tony Gilbertson provides a comprehensive list in an appendix of The Wellcome Witness Seminar exploring the history of British Intensive Care from 2010. See: Reynolds and Tansey, History of British intensive care, 107-8.

[7] Susan Hall and DL Perry, Crumpsall Hospital 1876-1976. ‘The Story of a Hundred Years’ (Littleborough: Upjohn and Bottomley, 1976). Susan Hall, Workhouses and Hospitals of North Manchester (Radcliffe, Manchester: Neil Richardson, 2004).

[8] Stephanie Snow, ‘“I’ve Never Found Doctors to be a Difficult Bunch”: Doctors, Managers and NHS Reorganisations in Manchester and Salford, 1948-2007’, Medical History 57/1 (2013), 65-86. Text provides a Manchester specific analysis of NHS reorganisation.

[9] Beth Abbit, ‘Single hospital service for Manchester’ as North Manchester General Hospital joins Manchester trust. North Manchester General Hospital (NMGH) has today joined Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT)’, Manchester Evening News (2021), <https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/north-manchester-general-hospital-joins-20301037> [accessed 17 July 2022]

[10] Reynolds and Tansey, History of British intensive care.

[11] Mark Hilberman, ‘The evolution of intensive care units’, Critical Care Medicine 3/4 (1975), 159-65.

[12] Ron V Trubuhovich and James A Judson, Intensive Care in New Zealand. A History of the New Zealand Region of ANZICS (Auckland, New Zealand: Dept. of Critical Care Medicine, Auckland, 2001); Wangari Waweru-Siika, Vitalis Mung’ayi, David Misango, Andrea Mogi, Alan Kisia, and Zipporah Ngumi, ‘The history of critical care in Kenya’, Journal of Critical Care 55 (2020), 122-7.

[13] Bjorn Ibsen, ‘Intensive Therapy: Background and Development’, International Anaesthesiology Clinics 37/1 (1999), 1-14.

[14] Reynolds and Tansey, History of British intensive care.

[15] Reynolds and Tansey, History of British intensive care, 23. US Health Department of Education and Welfare, The Progressive Patient Care Hospital. Estimating Bed Needs. A report based on findings of a Hill-Burton intramural research project, (Washington, DC: US Public Health Service Publication, 1963). World Health Organisation, The Organization of General Hospitals, Report on Conference, Oxford, 14th-19th November 1966 (Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 1966).

[16] North Manchester Hospital Management Committee. ‘27/01/1966 Minutes: item 7819. Progressive Patient Care (Minute 468)’, MC/Vol10/1966-68, Manchester Archives and Local Studies / Greater Manchester County Record Office. Manchester Central Libraries.

[17] Florence Nightingale, Notes on Hospitals, 3rd Edition (London: John. W. Parker and Sons, 1859). Unabridged reprint (New York, US: Dover Publications Inc. 2015).

[18] North Manchester Hospital Management Committee. ‘30/11/1967 Minutes: Item 8728. Intensive Care Unit (Minute 8702)’: MC/Vol10/1966-68, Manchester Archives and Local Studies / Greater Manchester County Record Office. Manchester Central Libraries. The 1967-2022 financial comparison calculation was made by accessing the website https://www.inflationtool.com < [accessed 18 August 2022]>.

[19] David Morrison, I tried Apollo, Honest! (Northumberland: Publisher’s name unknown, 2018). David Morrison, ‘Intensive Therapy at Crumpsall’, The Crumpsall Hospital Magazine (1968), 16-19. David Morrison, interview 29th October 2019.

[20] North Manchester Hospital Management Committee. ‘30.11.1967 Minutes: Item 8728. Intensive Care Unit (Minute 8702)’: MC/Vol10/1966-68, Manchester Archives and Local Studies / Greater Manchester County 21.12.67 North Manchester Hospital Management Committee MC/Vol10/1966-68.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Patricia Macartney, interview 17th January 2020.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Susan Hall, Workhouses and Hospitals of North Manchester, 29; Dianne McCann, interview 10th October 2019.

[26] Dianne McCann, interview 10th October 2019.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] The Salmon Reforms were designed to modernise nursing administration, in part by introducing a new grading structure and six tiers of nurse manager. The Salmon Reforms are discussed in detail in: Robert Dingwall, Anne Marie Rafferty and Charles Webster, An Introduction to the Social History of Nursing (London: Routledge, 1988), 114; and Geoffrey Rivett, From Cradle to Grave. Fifty years of the NHS (London: King’s Fund Publishing, 1998), 190-1.

[30] ‘Matron’s Letter’, dated 20th April 1972, published in The Crumpsall Hospital Magazine (1972), 5-7.

[31] Mark Gagan, interview 6th August 2020. ‘The Salmon Committee Report’, Nursing Times, 62/19 (1966), 625.

[32] Reynolds and Tansey, History of British intensive care, 91-102. Appendix 2, presents the outline curriculum for the original course as it developed.

[33] Ellen Chadwick, interview 11th November 2020.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Hugh Chadderton, interview 21st August 2020.

[36] Eric Sherwood-Jones, ‘The organisation and administration of intensive patient care, Postgraduate Medical Journal 43 (1967), 339-47.

[37] Morrison, I tried Apollo, Honest! 322-23.

[38] Patricia Macartney, interview 17th January 2020.

[39] Morrison, I tried Apollo, Honest!

[40] Maureen Lennon, ‘Coronary Care in Belfast’, Nursing Times 67 (1971), 921-4. The World Health Organisation, Nursing in Intensive Care: report on a seminar convened by the Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organisation Copenhagen 10-14 November 1969, (Copenhagen, World Health Organisation, 1969), 6.

[41] College of Paramedics. Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Inception of Paramedics. Available at: https://collegeofparamedics.co.uk/COP/News/celebrating_the_50th_anniversary_of_the_inception_of_paramedics.aspx [ Accessed 8th November 2022].

[42] K G Wright, ‘Extended Training of Ambulance Staff in England’, Social Science and Medicine 20/7 (1985), 705-12. Ian Macartney, personal correspondence – email 1st May 2015. Macartney as consultant anaesthetist and intensivist would work alongside Morrison in ICU at NMGH from the early 1980s, and subsequently take on the unit medical director role. He describes how from ‘around 1985’ he (Macartney) acted as senior medical advisor to the ambulance service in Manchester. At this time Manchester (now North West) Ambulance Service technicians began receiving training from medical staff (ICU and A&E consultants) in defibrillation, intubation, administration of life-saving drugs, and verification of death. Some trainees would gain experience during training with placements on the coronary care unit at NMGH. This is the forerunner of paramedic training in Greater Manchester.

[43] Patricia Macartney, interview 17th January 2020.