| Yuko Kawakami, Kameda University of Health Sciences, Japan | The UKAHN Bulletin |

| Volume 10 (1) 2022 | |

Introduction

This study investigates the background of the first women in Japan to become public health nursing teachers and the training they received in preparation to establish the first two recognised public health nursing schools in Japan. Although some male nurses existed in Japan at that time, the role was traditionally a female role and only women became public health nurses. Today in Japan, there are both female and male public health nurses and nurses, though the prevalence of women in these roles continues.

Most researchers in Japanese and English agree on the profound influence of St Luke’s Hospital and Nursing School on the training and education of nurses in Japan.[1] St Luke’s Hospital was founded by the physician and American missionary Dr. Rudolf Teusler in Tokyo 1902. Later, in 1920, St Luke’s Nursing School was established providing a three-year course in clinical nursing education. In 1925, Teusler felt the need for public health activities and invited Miss Nuno, an American public health nurse, to help found the department of public health nursing at St Luke’s, and in 1927, the department of public health nursing was founded within the hospital. In 1930, a one-year graduate follow-on progamme was added to the three-year course for those who wanted to learn about public health nursing before the appearance of official qualifications.[2] Graduates of St Luke’s worked at various institutions which became pioneers in public health nursing, such as public health centres, National Health Insurance Associations, and later, as instructors in public health nursing schools across Japan.

Aya Takahashi, in her 2011 book, The Development of the Japanese Nursing Profession, explored the growth of public health nursing during Japan’s interwar years through the efforts of St Luke’s Nursing School while highlighting the process of support from the Rockefeller Foundation to the Japanese government.[3] However, Takahashi focuses on the capital Tokyo in the time period before 1941. Information on training courses in areas other than Tokyo is lacking in the research literature. My study aims to address this gap (at least in part) by focusing on the training of teachers in preparation for the establishment of the first two recognised public health nursing schools in rural Japan.

What is presented in this article is part of a larger piece of work in which I aim firstly to understand the penetration of public health nurse training into rural areas of Japan, and secondly, how the role of public health nurses was connected to the characteristics of health needs in wartime Japan, such as the uneven distribution of doctors between cities and rural areas, the spread of infectious disease, and access to medicine.

In this article I aim to answer two questions regarding the early development of public health nursing in Japan: firstly, how was public health nursing training in pre-war and wartime Japan different from that of clinical nurses; and following on from that, to what extent did public health nurse training address the very different needs of rural and urban populations in pre-war and wartime Japan?

Brief history of nursing and public health nursing in pre-war and wartime Japan

The first clinical nursing training school in Japan was established in Tokyo in 1885 with a second founded in Kyoto in 1887. The Midwife Regulation, enacted in 1899 stated that those wishing to practice midwifery must pass an examination and be a minimum of twenty years old. As for nursing, although some prefectures had their own nursing regulations, these were only regulated at national level in 1915, when rules were established. Women who intended to become nurses had to be at least eighteen years old to sit the nurse examination conducted by the local governor, or to have graduated from a recognised clinical nursing training school. Despite this national regulation, the nursing examination was set by the local governor and therefore varied across the different regions of Japan.[4]

Public health nursing-like activities were seen in relief efforts after the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake and at a children’s health centre established by the Ministry of Home Affairs in 1926, which was based upon the British Children’s Health Centre Network.[5] Other early elements of public health nursing within Japan were provided by the Japanese Red Cross in Tokyo which offered a one year programme in what was called ‘social nursing’ (shakai kangofu). Between 1928 and 1937, it produced 114 graduates but was forced to stop training activities due to the worsening war situation overseas and its domestic impact.[6] Beginning with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931, Japan had begun a sustained period of war which continued for fifteen years, and included its involvement in WWII. In this long wartime period, urban populations were highly concentrated and some bad slum areas appeared, populated by many people living in poverty and unhygienic conditions, which gave rise to diseases such as tuberculosis. These conditions continued to deteriorate during the Sino-Japanese war.[7] Across Japan, the number of doctors – a traditionally male-dominated profession – were limited because men had to go to war. Lack of doctors was even more problematic in rural areas because most doctors preferred to work in cities where they could earn higher salaries.[8]

Having already begun training of clinical nurses in1920, in 1927, St Luke’s was officially recognised by the Japanese government as a higher-level vocational school. St Luke’s first offered its one-year graduate programme to train public health nurses from 1930, with financial support from the Rockefeller Foundation to the Japanese government; but although St Luke’s Nursing School was the top provider of training for public health nurses in Japan, its graduates did not receive official certification until the enactment of Public Health Nurse Regulation (July 1941) and the subsequent accreditation of St Luke’s (December 1941).[9]

The Japanese war effort really brought the state of the nation’s health to the government’s attention and can be viewed through the lens of the policy “Healthy body, healthy soldier”. To secure the necessary manpower for military ambition required a strong emphasis on health and hygiene, not just for the potential soldiers but also for the women at home. Most young and middle-aged men were away from their homes, fighting or involved in military matters and as a result, women were forced to take up men’s work, such as heavy labour, while still caring for and nursing their children. If children were not well taken care of, they would not grow to be healthy soldiers. Only women’s shoulders carried both burdens. A lot was expected of them during this period. It was in this context that activities for public health nurses really started to emerge.[10]

Prior to the Sino-Japanese war, most nurses in Japan worked in hospitals. The idea of public health nursing was not widely known or understood outside the small coterie of women who took the public health nursing course at St Luke’s, but in 1937 a total of forty-nine public health centres appeared across Japan simultaneously, at least one in each prefecture.[11] The Public Health Centre Act identified the ‘public health nurse’ for the first time as a profession. Each public health centre was to have at least three public health nurses but very few were professionally trained, and until 1941 there were cases where women were hired because they were qualified as clinical nurses.[12] Some women who worked in these centres as public health nurses attended the public health nursing course held in St Luke’s Nursing School between August 1938 to February 1939, with the support of the Ministry of Health and Welfare. They then went on to perform duties similar to that of public health nurses.[13]

In April 1938, the National Health Insurance Law was enacted as a relief measure for rural residents, establishing the National Health Insurance System as a solution to the issues of the poor medical system and unhygienic environment in rural areas.[14] It was funded partially by national government together with a contribution by individuals. Before this, poor people, especially in rural areas, could not afford medical treatment. To achieve the government’s recommendation of population growth to secure healthy human resources and stability of life in rural areas, policy aimed to grow the population through lowering child mortality and decreasing death rates from tuberculosis. To implement this national project at local level, National Health Insurance Associations spread. As well as covering 70% of the costs, various activities were carried out for health promotion, such as community education on nutrition and home visits.[15] These associations provided assistance with medical expenses and gave health guidance from public health nurses, initially unlicensed, until the license system came into effect in 1941.[16]

In Japan, the public health nursing regulation was enacted by Health and Welfare Ministry Ordinances in July 1941.[17] Under the policy of ‘healthy people and healthy soldiers’, public health nurses and public health nursing students practiced improving the hygiene of the daily living environment of residents and disseminating hygiene knowledge in the rural communities in which they worked. In this occupational history, public health nurses were trying to spread, permeate and take the lead in promoting the value and norms of hygiene to all residents. When public health nurses were recognised as a new category of occupation, the Japanese public was supportive and became more interested in personal healthcare and quality of life issues. Whereas clinical nurses had mainly worked in hospitals, the new profession of public health nurses worked in local National Health Insurance Associations, health centres (as they developed) and various municipal institutions, such as village offices, schools and agricultural cooperatives.[18]

Japanese education system and nursing education

Compulsory education in Japan for both boys and girls began in the late nineteenth century. Students had to attend elementary school until at least age twelve though it was not strictly enforced. For boys, there was 97% enrollment in elementary education by 1904 and girls reached a similar level by 1909.[19] After elementary school, only the best performing girls had the opportunity to attend higher girls’ school (that corresponded to junior high school for boys) for a further five years (aged twelve to seventeen). By 1930s, less than 15% of female students went on to higher girls’ school.[20] Of those who did not go to a higher school, girls who wanted or were able to continue education could go onto a two-year programme at an upper elementary school before finding employment. Graduates of upper elementary school (who would be aged 14) who wished to obtain a nursing or midwifery license could then go onto on-the-job training.[21]

While graduates of the upper elementary schools were admitted to nursing or midwifery courses, the new public health nursing schools required a different level of qualification. Between 1941 and 1945 the public health nursing schools were designated Type 1, 2 and 3. The latter two would admit women, who had graduated from upper-elementary school and subsequently gained either a nursing or midwifery license, onto short courses (6 months or 1 year). But Type 1 schools accepted only graduates of higher girls’ schools. These students required no nursing or midwifery qualifications prior to enrolling, but joined two-year courses which incorporated general and public health nursing.[22] (See Table 1) Hamada and Matsue Schools in Shimane Province (which are the focus of this study) were both designated Type 1 schools when they opened in 1941.[23]

| Type of License | Minimum school education level | Earliest possible age at start of training | Minimum Entry Requirement | Minimum Training Duration | Subjects Covered | Outcome |

| Type 1 | Higher girls’ school | 17 | Graduate Higher girls’ school | 2 years | Liberal arts, Medicine, Nursing, Social welfare, Public health, Public health nursing | Public health nurse license

Nurse license |

| Type 2 | Upper elementary school | 18 | Nursing License | 6 months | Social welfare, Public health, Public health nursing | Public health nurse license |

| Type 3 | Upper elementary school | 20 | Midwifery License | 1 year | Nursing, Social welfare, Public health, Public health nursing | Public health nurse license |

Table 1: Three types of public health nurse license in Japan 1941.

Admission to Type 1 training schools was thus only open to those who had graduated from a higher girls’ school, and as only the top achieving girls in elementary school were allowed to enter higher girls’ school, this meant Type 1 public health nursing schools were taking only the best female students. Over the next two years, these students would gain both their public health nursing license and their nurse license, even though they had no prior nursing training. During training, at least 1,200 hours had to be spent in clinical nursing practice and at least three months in practical training for public health nurse work at public health centers and other appropriate facilities as defined under the Public Health Center Law.[24]

By contrast, admission to Type 2 public health nursing training was open to qualified nurses. Although they had already passed their nursing examination, the majority of these students had a lower level of education, as many Type 2 training schools only required completion of upper elementary school as a prerequisite to starting their three-years clinical nursing training. Type 2 training could last as little as six months. Finally, Type 3 programmes were open to qualified midwives. Their training lasted a minimum of one year of which at least 600 hours had to be spent in clinical nursing practice, and three months in practical training for public health nursing at public health centers and other appropriate facilities in accordance with the Public Health Center Law.[25]

In July 1941 when the public health nurse was recognised as a new higher specialty profession, this offered an opportunity for women to continue their education beyond the age of seventeen at a time when such opportunities were rare. Obtaining the license meant families had given permission for these women to further their studies, in a system otherwise largely closed to women.[26] In this way, women who received public health nurse education advanced their basic education.

Methods

This study analysed primary historical documents of the first two accredited public health nursing schools in Shimane prefecture in western rural Japan: the public health nursing schools of Matsue and Hamada. The establishment of both of these schools was funded by a consortium of three associations: Social Work Association, Patriotic Women’s Association (a women’s political action group) and the Military Support Association.[27] The Japanese government recognised them as official public health nurse training schools. Both these schools offered type one two-year programs.[28]

In addition, data was collected through interviews which were conducted between 2010 and 2014 with seven retired public health nurses who graduated in the first cohort in 1942 from either of these two schools. At the time of the semi-structured interviews, participants were aged between eighty-six and ninety-two years old.

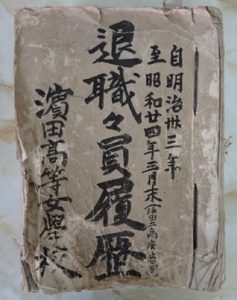

The research also used administrative documents of the schools including the teachers’ résumés, which detail the personal, school and work history of all faculty members, shown in figure 1 below.

Training the Trainers

Having decided to establish schools of public health nursing, the authorities needed to identify and prepare a cohort of teachers who could develop and implement the curriculum for public health nurse education. This section will investigate how this happened.

In 1940 a local newspaper in Shimane Prefecture ran an article under the title ‘Looking for a Female Assistant’ which outlined the qualifications for teachers at the soon-to-be opened Matsue and Hamada public health nursing schools. Applicants should be under thirty-five years old, licensed as midwives or nurses and have graduated from higher girls’ school or equivalent.[30] Eight women were selected on the condition that they were qualified midwives or nurses and were excellent in terms of character, academic ability and practical skills.[31] Participants in the programme would receive further education in Tokyo for three months from June to August 1940.[32] These eight women are shown in the photo in Figure 2 below, when they returned to Shimane prefecture in late August 1940.

By leaving their home towns, often for the first time, these nursing teachers learned to look at their situation more objectively. One of the interviewees reflected, ‘Despite living in a rural area, I had not understood the hygiene situation well. It was not until I came to Tokyo and received training that I understood the hygiene situation in rural areas. I recognised the need for ingenuity in maternal and child health.’[36] “Ingenuity” here could refer to the need for creativity and use of alternative supplies during the scarcity of wartime, especially in rural areas. One example of this was given by one of the interviewees, Keiko, who explained that futons (bedding) were cut up to be used in place of absorbent cotton during childbirth.[37]

Their comments showed the eagerness of local populations for improving health in their home towns. ‘We visited several facilities and found that the enthusiasm of the local people was strongly reflected in the improvement of public health.’[38] This enthusiasm helped the trainees realise that there were many things they could do to help, even within the wartime environment, and that their skills in public health nursing could be very useful to the community.

Participants also noted connections formed with local communities, observing that improving health in this way requires the cooperation of inhabitants. One participant commented that, ‘I think that more important than health skills and knowledge is being close to the people. I want to make an effort to improve the health of our home town’.[39] With the public not really understanding the concept of public health nursing, this more collaborative role of public health nurses within communities perhaps contrasted to earlier encounters the public had with clinical nurses in hospitals. These particular skills remain important in public health nursing today.

A second newspaper article described the eight trainees as the ‘Mothers of social public health nursing’ when they returned home to Shimane prefecture from Tokyo after their training.[40] When they returned, the eight women continued their practical training in Iwasaka village in rural Shimane. With a population of 2447 across 413 households in 1935, Iwasaka had been selected as one of sixteen ‘designated villages for hygiene’ and received funding as part of the Imperial Gift Foundation’s campaign to protect expectant mothers and infants in rural areas.[41] The eight women provided hygiene education to Iwasaka residents (the context of this education, whether classroom-based or otherwise, cannot be inferred from the data), practiced home visits and provided childcare services in a nursery.[42] A third article described the field activities of the eight women before they were assigned to their schools to begin their role as public health nursing educators. This article titled ‘Flooded with clients; sweaty home-visit activities’, highlighted how busy the nurses were.[43]

With this additional month of practical training, the eight women were then ready to take up the teaching roles once the schools opened on 1 October 1940, four each at Hamada and Matsue public health nursing schools. Mr Seizo Kato, the prefectural Director of Academic Affairs, led the founding of both schools. He stated that public health nurses were servants of society and needed more than just healthcare skills. Public health nurses were to be life instructors and social workers.[44] This vision for public health nursing is demonstrated through the entry requirements of the two schools, namely that they were open only to higher girls’ school graduates who had a relatively strong academic ability and a foundation in liberal arts.[45]

Hamada Public Health Nursing School did not have independent premises. The first twenty-three students took their classes in a room at the local higher girls’ school. It was similar at Matsue, where 35 new students were accepted in its founding year. Data was extracted from the administrative documents of the two schools (an example of the sources is shown in Figure 1) on ten teachers appointed between 1940-1945 at the Hamada or Matsue Public Health Nursing Schools. It included the work histories of five of the eight trainees previously discussed.[46] All ten teachers originally came from rural areas in Japan, mostly from Shimane prefecture itself, but also from other rural areas across Honshu, the main island of Japan. At the time of appointment they were aged between eighteen and twenty three years old: three of the teachers had no previous work experience, the others had varying degrees of experience from nine months to five years, including work as nurses in schools, hospitals and a medical department of a local university. Nine teachers were qualified as nurses; and one was a home economics teacher. The first teachers appointed when the schools opened in1940 (with the exception of the home economics teacher) had obtained their nursing or midwife licenses at various educational institutions in Western Japan and completed their three-month practical training in Tokyo; but obviously, given that this qualification did not exist at the time, the very first teachers were not qualified as public health nurses themselves. The three teachers who were appointed in 1941 or later completed their programme of training at St Luke’s Nursing School, had gained a public health nursing license (from the Ministry of Health and Welfare).[47] Among them, Ms Sada Miura,[48] appointed in September 1941 as the first public health nursing teacher with a public health nurse license and became a very significant teacher in both schools. All of the interviewees highlighted how important Ms Miura was in their training and development, as she was able to help them understand the difference between public health nursing and general nursing.

The curriculum, as well as including training in medical subjects such as anatomy and bacteriology, also required students to complete fifty hours of classroom learning on health of communities (targeting health within schools, factories and social communities) and thirty-five hours on individual health (targeting house, clothing and airing, and waste treatment). In addition, students received six-months of practical training. In this way, the curriculum aimed to encompass health issues affecting the full spectrum of community members: students were also trained in social work, social insurance and health statistics. Looking to provide its students with a broader education, the curriculum was enhanced with courses on Liberal Arts such as education, ethics and women’s issues.[49]

Challenges in this Research

One of the major challenges encountered in this study has been in the availability of primary sources. This research focuses on experiences eighty years ago and includes use of first-hand accounts. Interviews were conducted with elderly women (former public health nurses) recollecting and interpreting events and experiences from memory. There are a diminishing number of people surviving to tell their story or to cross-reference captured stories with.[50] In addition, the documents available are not consistent across institutions – for example, while a detailed list of nursing teachers in Hamada Public Health Nursing School at the end of WWII provides rich data, no equivalent exists at Matsue School. These women’s stories are valuable and should be told even if incomplete.

Another difficulty encountered is bringing this research to a non-Japanese audience, primarily as a result of the language barrier. The majority of the existing research on nursing history in Japan is in Japanese only. I have focused on teachers at two training schools in rural wartime Japan but to bring new research to a global audience involves not only presenting the research itself, but includes an attempt to contextualize it within an area that readers may know little about. Beyond this is the translation of terms themselves, for example, those used in the education system at the time, or the names of specific licenses, which readers are likely to interpret with reference to the systems they are most familiar with, though they may not be equivalent. Also, as the education system evolved over this period, there was overlap between terms used for different levels of education.

Finally, another theme in the broader research project of which this is part, is that at a time in Japan when there was very little concept of public health nursing, it is important to gain perspective of how the Japanese women who studied in America were influenced in their nursing practice when they returned to Japan. I had planned to visit the Rockefeller Archive Center (New York) in 2020 but due to travel restrictions during the pandemic, I was unable to go which means a crucial element of this research is still to be undertaken. I plan to visit the archives in late 2022.

Initial conclusions

It is too early to draw conclusions on the differences in training for public health nursing in urban and rural populations. The first teachers at Shimane’s schools had had limited training at a rural health centre, with their initial training period in Tokyo being followed by a month’s practical training in Iwasaka. Their students, however, received at least thirty hours of classroom training on rural health alongside six-months practical training. It will be interesting to compare the curriculum at these rural public health nurse training schools with that of St Luke’s, a typical urban school.

My research has so far found that the philosophy behind clinical and public health nursing in Japan was broadly different, in the period under study and emphasizes different skills. Whereas clinical nursing focused mainly on nursing skills alone, Matsue and Hamada schools more highly valued social work skills. Perhaps the newspapers’ frequent reporting of the recruitment of teachers and opening of public health nursing schools was to help educate the public about the emerging roles and philosophies of public health nursing in Japan.

References

[1] See Aya Takahashi, The Development of the Japanese Nursing Profession: Adopting and Adapting Western Influences (New York: Routledge, 2011); Kathleen M Nishida, St. Luke’s College of Nursing, Tokyo, Japan: The Intersections of an Episcopal Church Mission Project, Rockefeller Foundation Philanthropy, and the Development of Nursing in Japan, 1918-1941 (A Dissertation in Nursing Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 2016). https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3705&context=edissertations [Accessed online 26 November 2022); Hiro Fujimoto, Igaku to Kirisutokyo: Nihon niokeru America Protestant no Iryo Senkyo [Medicine and Christianity: American Protestant Missionaries and Their Medical Work in Japan] (Tokyo: Hosei University Press, 2021).

[2] 50nen-shi Henshu Iinkai, Seiroka Kangodaigaku 50nen-shi [St Luke’s College of Nursing 50 Years History] (Tokyo: St Luke’s College of Nursing, 1970).

[3] Takahashi, The Development of the Japanese Nursing Profession.

[4] Kouseisho Imukyoku [Ministry of Health and Welfare], Isei Hyakunenshi: Kijutsuhen [A Centennial History of the Medical System] (Tokyo: Gyosei, 1976), 92-95.

[5] Masayasu Kusumoto et al., Hokenjo 30nen-shi [Public Health Centre 30 Years History] (Tokyo: Japan Public Health Association, 1971), 25-28.

[6] Mari Tsuruwake et al., Senzen Senchuki nimiru Seiroka to Nihonsekijujisha no Koshueisei Kango to sono Kyoiku no Tokucho [‘Public Health Nursing by St. Luke’s International Hospital and St. Luke’s College of Nursing and the Japanese Red Cross Society, and Characteristics of Their Education Prior to and during World War II’], Bulletin of St. Luke’s International University, 2 (2016), 1-9: 5.

[7] Kujuro Fujiwara, Senjika Shimin Eisei no Mondai [‘The Issues of People’s Hygiene in Wartime’] Toshi Mondai, 31/2 (1940), 223-238; Masayasu Kusunoki, Noson to Kekkaku Yobo [Rural Communities and Tuberculosis Prevention] (Tokyo: Dainippon Kyoka Tosho, 1942).

[8] Kokumin Kenko Hoken Kyokai, Kokumin Kenko Hoken Shoshi [A Brief History of National Health Insurance System] (Tokyo: Kokumin Kenko Hoken Kyokai, 1948), 14-18.

[9] Ministry of Health and Welfare Ordinance No. thirty six. Kanpo [Official Gazette] 4351 (10 July 1941), 333.

[10] See Hideko Maruoka, Nihon Noson Fujin Mondai: Shufu Bosei hen [Rural Women’s Issues in Japan: Housewives and Motherhood] (Tokyo: Koyo Shoin, 1937); Denzo Furuse, Tatakau Noson Fujin [Rural Women in War] (Tokyo: Shubunkan,1942); Tadashi Fukutake, Rural society in Japan (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1980).

[11] Masayasu Kusumoto et al., Hokenjo 30nen-shi [Public Health Centre 30 Years History] (Tokyo: Japan Public Health Association, 1971), 71.

[12] Shimane-ken Kango Kyokai [Shimane Nursing Association], Kaiko [Recollection], (Shimane: Shimane-ken Kango Kyokai, 1986), 29.

[13] Masayasu Kusumoto et al., Hokenjo 30nen-shi [Public Health Centre 30 Years History] (Tokyo: Japan Public Health Association, 1971), 97.

[14] Law No. sixty. Kanpo [Official Gazette] 3371 (1 April 1938), 13-16.

[15] Koseisho Hokenkyoku [Ministry of Health and Welfare], Kokumin Kenko Hoken Shoshi [A Brief History of National Health Insurance System] (Tokyo: Kokumin Kenko Hoken Kyokai, 1948).

[16] Michiko Okuni, Hokenfu no Rekishi [History of Public Health Nurses] (Tokyo: Igaku Shoin, 1973),124-126.

[17] Koseisho Imukyoku [Ministry of Health and Welfare], Isei Hyakunenshi: Kijutsuhen [A Centennial History of the Medical System] (Tokyo: Gyousei, 1976), 302.

[18] Nihon Iryodan Chosabu, ‘Zenkoku Hokenfu Fukyu Bumpu Jokyo to Yosei Kikan Setchi no Genjo’ [‘Current Status of the Diffusion and Distribution of Public Health Nurses and the Establishment of Training Institutions in Japan’], Nihon Iryodan Joho, 2 (1943), 1-25: 7-8.

[19] Yoshizo Kubo et al., Gendai Kyoikushi Jiten [Dictionary of Contemporary Educational History in Japan] (Tokyo: Tokyo Shoseki, 2001), 78.

[20] Ibid., 96.

[21] Nihon Kango Rekishi Gakkai, Nihon no Kango no Ayumi [History of Nursing in Japan, 2nd ed.] (Tokyo: Japanese Nursing Association Publishing Company, 2014), 78.

[22] ‘Shiritsu Hokenfu Gakko Hokenfu Koshujo Shitei Kisoku’ [‘Designated Rules for Private Public Health Nursing schools, Public Health Nurse Training Schools’], Shakai Jigyo, 25/9 (1941), 118-119.

[23] Mitsu Kaneko, Kango no Tomoshibi Takaku Kakagete: Kaneko Mitsu Kaikoroku [Holding a Lamp of Nursing High: Memoirs by Kaneko Mitsu] (Tokyo: Igaku Shoin, 1994), 67.

[24] ‘Shiritsu Hokenfu Gakko Hokenfu Koshujo Shitei Kisoku’ [‘Designated Rules for Private Public Health Nursing schools, Public Health Nurse Training Schools’], 118.

[25] Ibid., 119.

[26] Yuko Kawakami, Nihon niokeru Hokenfu Jigyo no Seiritsu to Tenkai: Senzen Senchuki o Chushinni [Formation and Evolution of the Public Health Nursing in Prewar and Wartime Japan] (Tokyo: Kazamashobo, 2013): 198-201.

[27] Shimane-ken Shakai Jigyo Kyokai [Association of Shimane Prefectural Social Work], Shimane-ken Shakai Hokenfu Yoseijo narabini Kotojogakko Hokenka no Gaiyo [Overview of Shimane Public Health Nursing School and Health Education Curriculum in Higher Girls’ School] (Shimane: Shimane Prefectural Public Health Nursing School,1942), 8-10.

[28] Mineko Fujii, ‘Hokenfu Jigyo no Genjo: Dai 4kai Nihon Hokenfu Taikai Bochoki’ [‘Current Status of Public Health Nursing: Report on the 4th Japan Public Health Nurses’ conference’] Nihon Iryodan Joho 7 (1943), 4-23: 22.

[29] Hamada High School, the present day successor to Hamada Public Health Nursing School, had these original documents in their possession. It included the list of teachers at Hamada higher girls’ school in Shimane prefecture 1900-1949, including the public health nursing school which opened in 1940.

[30] Osaka Mainichi-Shimbun Shimane-ban, 11 May 1940.

[31] Shimane-ken Shakai Jigyo Kyokai [Association of Shimane Prefectural Social Work], Shimane-ken Shakai Hokenfu Yoseijo narabini Kotojogakko Hokenka no Gaiyo [Overview of Shimane Public Health Nursing School and Health Education Curriculum in Higher Girls’ School], 9.

[32] San-in Shimbun, 27 August 1940.

[33] Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin [Shimane Prefectural Public Health Nursing School], Kusawake no Hokenfu Yosei [Pioneer in Training Public Health Nurses] (Shimane: Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin,1985), 14.

[34] The Imperial Gift Foundation was established in 1934. It was positioned as an affiliated organisation of the government. The Foundation was endowed with money given to commemorate the birth of the Crown Prince of Japan. It was involved in a wide range of child and maternal education and care activities, and was a leader in wartime maternal, child hygiene and infant protection. Naoko Yoshinaga, ‘1930nendai niokeru Noson no Saniku heno Kanshin to Shisaku: Onshizaidan Aiiku-kai no Jigyo kara’ [‘A Study on the Childbirth and Childcare in Japanese Rural Communities in the 1930s: An Analysis of the Policies and Problems of the Imperial Gift Foundation “Aiiku-kai”’], Departmental Bulletin Paper, The Department of History and Philosophy of Education, Graduate School of Education, The University of Tokyo, 29 (2003), 1-13.

[35] Usaburo Katayose, ‘Hokenka Keiei Shokan’ [‘Impressions on the health education curriculum’], Kyoiku 10/12 (1942), 465-478: 472: Hokenfukai Shimane-ken Shibu [Shimane Nursing Association, Public Health Nurses Section], Hossoku 20shunen Kinenshi [Commemorative Publication for the 20th Anniversary of Foundation of the Shimane Public Health Nursing Association], (Shimane: Hokenfukai Shimane-ken Shibu, 1962), 44-49; Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin [Shimane Prefectural Public Health Nursing School], Kusawake no Hokenfu Yosei [Pioneer in Training Public Health Nurses] (Shimane: Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin,1985), 48-51; Shimane-ken Kango Kyokai [Shimane Nursing Association], Kaiko [Recollection], (Shimane: Shimane-ken Kango Kyokai, 1986), 36-38.

[36] Osaka Asahi-Shimbun Shimane-ban, 28 August 1940.

[37] Keiko Ino (pseudonym) Interview by Yuko Kawakami, 14 April 2010.

[38] Osaka Asahi-Shimbun Shimane-ban, 28 August 1940.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Osaka Mainichi-Shimbun Shimane-ban, 27 August 1940.

[41] Onshizaidan Aiiku-kai, Aiiku-son no Soshiki to Jigyo [Organization and Projects about “Aiiku-son”] (Tokyo: Onshizaidan Aiiku-kai, 1939).

[42] For practices in other villages during the same period, see Hiromu Yoshida, Aiiku no Mura: Arashima [“Aiiku-son”: Arashima] (Tokyo: Kyodo Kosha, 1944), 191-200.

[43] Osaka Mainichi-Shimbun Shimane-ban, 18 September, 1940.

[44] Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin [Shimane Prefectural Public Health Nursing School], Kusawake no Hokenfu Yosei [Pioneer in Training Public Health Nurses] (Shimane: Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin,1985), 10.

[45] Yuko Kawakami, Nihon niokeru Hokenfu Jigyo no Seiritsu to Tenkai: Senzen Senchuki o Chushinni [Formation and Evolution of the Public Health Nursing in Prewar and Wartime Japan] (Tokyo: Kazamashobo, 2013), 228.

[46] See End Note 29 above.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin [Shimane Prefectural Public Health Nursing School], Kusawake no Hokenfu Yosei [Pioneer in Training Public Health Nurses] (Shimane: Shimane Kenritsu Hokenfu Semmon Gakuin,1985), 60-75; Nagano (Miura) Sada Kaisoroku Kanko Iinkai, Nagano (Miura) Sada Kaisoroku [Memoirs of Ms Sada Nagano (Miura)], (Fukuoka: Toka Shobo, 1990).

[49] Association of Shimane Prefectural Social Work, Shimane-ken Shakai Hokenfu Yoseijo narabini Kotojogakko Hokenka no Gaiyo [Outline of Shimane Public Health Nursing School and Health Course in Higher Girls’ School] (Shimane: Shimane Prefectural Public Health Nursing School,1942), 17-19.

[50] The need for cross referencing (or triangulating) information gained through interviews is a well-known challenge in oral history, see for example, Paul Thompson, The Voice of the Past: Oral History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). Japanese literature on oral history tends to focus more on political science history and policy-making process, see for example, Masaharu Gotoda, Jo to Ri: Kamisori Gotoda Kaikoroku [Emotion and Reason: Memoirs by Gotoda], Takashi Mikuriya, ed., (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2006).