David Stewart i

A former nurse, now suffering with dementia, was admitted to the Prestwich Asylum near Manchester in 1889. In her case notes it records that she thought she was twenty and that the year was 1860. However, when prompted she would recall Miss Nightingale and the hospital at Netley.ii The nurse was Mary Barker, the first Nurse to be recorded in the Nightingale School of Nursing Probationers’ Record Book in 1860 and crucially Mary came from Beeston, just outside Nottingham.iii Mary was one of twenty-five working class women from Nottinghamshire who went to train as nurses at St Thomas’s Hospital in the 1860s. These were the very women – those ‘belonging to classes in which women are habitually employed in earning their own livelihood’ – for whom the Nightingale Fund Council thought the new nurse training scheme would be most useful.iv

In recognition of her work in the Crimean War, the British people raised some £45,000 and Florence Nightingale directed that it should be used to create a school of nursing. The Nightingale Fund Council, appointed by her in 1856, worked for four years before her plan came to fruition. The surviving archives of the Council and the Nightingale School of Nursing are held at the London Archives.

This study is based on the probationers recorded in Book A or the Red Book which dates from 1860-1871, and as Mary was the first, so the final probationer in that book, Alice Keywood, was also from Nottinghamshire. Remarkably 10% of the total, some twenty-five women came from Nottinghamshire. Their subsequent careers were closely allied to Nightingale’s ambitions for the scheme. Indeed, a third of the women who accompanied Agnes Jones to the Liverpool Workhouse were from Nottinghamshire.

So, who were these women and why did so many come from the same county? When the Nightingale Fund Council finally came to an agreement with the authorities at St Thomas’s Hospital for the training school to be sited there, they gave themselves little time. With a course due to begin on the 24 June 1860, the first provincial newspaper adverts were only published in early June, and one has not been found yet in a Nottinghamshire paper. So how did people know about this new training scheme? In the case of Nottinghamshire, as elsewhere, it was the members of the Nightingale Fund Council who were encouraged to use their networks and contacts and who provided the conduit to recruiting Nottinghamshire women.

Figure 1 Mrs Anne Enfield with kind permission of University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections

One of the Fund Council members was the surgeon William Bowman, a close ally of Florence Nightingale. Bowman’s wife, Harriet, a Unitarian, was a cousin to Charles Paget the MP for Nottingham. Paget’s sister-in-law, Harriett Tebbutt, had served in the Crimea as Superintendent at the Scutari General Hospital. The Unitarian network was a powerful force and in Nottingham the Unitarians held most of the public posts. The wife of the town clerk was Anne Enfield, whose family connections included, Martineaus, Gregs, Rathbones, Needhams and Philipses. Her best friend, Catherine Turner, cousin of Harriet Martineau, ran a girls’ school in Nottingham which attracted girls nationally from the many leading Unitarian families. Jemima Clough, sister to the secretary of the Fund Council, was well known to Turner and Enfield through Harriett Martineau. All these connections were crucial in making the scheme known.

Before her death in 1865 from cancer, Anne Enfield had recommended eighteen of the twenty-five Nottinghamshire women who appear in book A. Well educated, she was keen to promote the cause of the training of nurses as well as providing opportunities for working women to improve themselves. No other referees came near to this number of women, Agnes Ewart from Manchester with five being the next biggest single sponsor. Ewart, also a Unitarian, attended chapel with Mark Philips, the first MP for Manchester, who was a cousin of Enfield.v

An examination of the lives of these probationers, recommended by the Nottinghamshire network shows that they were all working class women, many of whom would have been working since the age of eight or ten so when Barker went to train, at thirty-two, she had already been working for twenty years. The majority worked in the town’s lace industry. Conditions in the lace dressing rooms were particularly bad, with women and girls often working in temperatures of over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Consumption was very common amongst warehouse girls and two of the Nottinghamshire probationers were dismissed on concern that they were consumptive and not strong enough for the task. The opportunity for alternative employment must have been very attractive.

Nottingham from the time of the English Civil War had been seen as a city of protest and non-conformity was a strong presence. Whilst 70% of the women named in the Red Book were Church of England, the Nottinghamshire cohort were 79% non-conformist, with one Catholic. Enfield supported women from all denominations, unlike clergymen who only supported those of their own congregation. A requirement of the probationers was that they should be able to read and write and whilst it is not known where each woman received her education, from the 1830s the government was giving grants to British and National schools. The non-conformists supported many Sunday Schools some of which taught writing as well as reading.vi

For all these women, family was a very important factor in their ability to leave Nottingham. The majority were single. Some might have been expected to help with the care of an elderly parent, though some had a sibling who undertook that role. Others had to wait for their parents to die. One relied on her parents to provide childcare for her two young children whilst she went away to London. Another woman was separated from her husband. vii

The Council had agreed on the age for acceptance being between twenty-five and thirty-five, though clearly what age was given to Mrs Wardroper was not always accurate, with applicants either adding on years because they were too young or losing years because they were over thirty-five. Marian Bradbury was only twenty-one though claimed to be older. Deborah Burgess was approaching forty but claimed to be thirty-four. The age limit was not absolute, and Ellen Pattison was admitted at thirty-nine.

For some women, the journey to London would be their first time on a train and the first time visiting the Metropolis. Three had lived in Calais, not uncommon in Nottingham history because of the town’s lace trade with the continent, so would have had some experience of travel but for the majority this would have been a new adventure possibly full of apprehension or excitement. With no evidence I presume that Mrs Enfield helped with train fare and other subsidies.

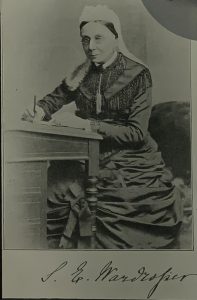

Figure 2 Mrs Wardroper with kind permission of the Florence Nightingale Museum

Welcomed by Mrs Wardroper the Matron and Lucy Bull, her assistant, the women were to be paid £10 a year and after the completion of a further year would be added to the register of trained nurses, with a bonus of £5 for first class nurses such as Mary Barker and £3 for second class, such as Eliza Trueman. Registration was not automatic and Marian Bradbury, who had an eye for the medical students, had to wait two years before her behaviour was considered appropriate.viii There was an expectation that the nurses would be attached to the school for a least three years and be prepared to go where they were sent. Other historians such as Lucy Seymer, Monica Baly and Roy Wake have written about the training provided, particularly the classes provided by Richard Gullett Whitfield, the house surgeon although very little about the practical nursing provided by Lucy Bull and her team of sisters. Some of these authors such as Monica Baly and Roy Wake have been dismissive of the impact of the nursing in that first decade in terms of turning out future leaders, but arguably they have missed the impact to the individual nurses.ix The probationers were offered a professional paid training, the chance to travel and to experience new environments. For those with marriage in mind, there was wider choice of husband. Two thirds of the Nottinghamshire cohort would go on to get married, becoming mothers or stepmothers.

Figure 3 Mary Barker, with kind permission of the Florence Nightingale Museum

Mary Barker, the first nurse on the register, had lost her father at an early age and she worked with her mother and sisters as a laundress, a hard and potentially dangerous job.x At the age of thirty-two, she would have been working for some twenty years prior to beginning her training in 1860. She began her training at St Thomas’ Hospital on the old Southwark site, working under the Sisterso of, North, Luke, Isaac and Queen, therby gaining experience on medical and surgical wards.xi After completing her training, she worked as a temporary sister at St Thomas’s for three months before she was sent to the female hospital at the Woolwich Barracks. On 24 June 1862 she was sent to the military hospital at Netley, under Miss Shaw Stewart, another veteran of the Crimea and a very autocratic Lady Superintendent. Shaw Stewart would only accept nurses who were Church of England. Mary as a devout Anglican fitted the bill whilst her non-conformist colleagues dodged the bullet of working for Shaw Stewart. Barker returned to St Thomas’s in May 1866, working as Sister Accident. Wardroper noted that ‘she is a good nurse and her patients (though not at all times so tenderly treated as they might be) will never suffer from neglect. An excellent nurse, very respectable but has a temper.’xii Nightingale, whilst thinking that she would get on with Mary, noted ‘I think I should have seen even without being told, that her temper was … possessed with a devil.’xiii

In 1867 came the opportunity to accompany Lucy Osburn and four other nurses to Australia to be a head nurse at the Sydney Hospital. Mary was shocked by the conditions in Sydney as she was to write to Nightingale, ‘I think the scrubbers at St Thomas’s were a respectable class of women in comparison with what we found as day nurses at Sydney Infirmary.’ She thought the local nurses were slatternly with enormous crinolines and hair which had not been combed for a week. Vermin were everywhere.xivNightingale is known to have sent many letters to Barker to keep up her morale.xv When Queen Victoria’s son Alfred needed nursing in Sydney, although Mary was the most competent and experienced surgical nurse, Osburn chose Haldane Turriff, who was better educated and perhaps less rough around the edges. However, Mary remained loyal to implementing the Nightingale System and indeed to Lucy Osburn. When the three-year contract was finished, the other English nurses were let go apart from Mary who would deputise at the hospital when Osburn was absent. A Royal Commission in 1873 which included the management of the hospital, and particularly the nursing system, saw Mary as a witness stoutly defending Osburn.xvi

Osburn repaid the loyalty poorly by forcing Mary to resign, and so she returned to England in 1873. She may have been planning this for in a letter to Nightingale in May 1873, Osburn noted that, ‘Barker is well and saving heaps of money.’xvii After some private work and working at St Thomas’s Miss Pringle, superintendent at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, requested Mary to come as Night Superintendent, an unrelenting post which she filled nightly for two years.

Conditions in the Infirmary on Drummond Street were far from ideal with patients sharing beds or sleeping on mattresses on the floor. During her time Joseph Lister and a young Alfred Conan Doyle were on the staff. In 1877 she was promoted to Matron of the Convalescent Home at Corstophine. At first the Infirmary Governors appeared very pleased with her work, but by 1882, she had resigned when questions were asked about the management of the home. The imprisonment in 1880 of her beloved elder brother for stealing may well have unsettled her.xviii She moved to Lancashire to be near her nephews and the death of her brother in 1885 is said to have begun her decline resulting in her admission to the Prestwich Asylum.xix

Other Nottinghamshire pioneers would be sent to Liverpool Royal Infirmary, Brownlow Hill Workhouse, Cardiff, Swansea, Leicester, Derby, Winchester, Northampton, Dorset and Devonport. Nightingale dismissed the importance of referees but a greater study of the men and women who recommended candidates helps to locate the origins of the probationers and how they learnt of the Nightingale Scheme.xx As with Anne Enfield, the referees saw an opportunity for these working-class women, to access training and be given improved employment opportunities.

And where is the head stone of the first Nightingale Nurse? Mary, with little chance of recovery, was sent to the Annexe at Prestwich for chronic and quiet incurable patients where she died in 1891. Patients at Prestwich were buried in communal graves without a headstone. In 2006 a generic memorial was erected to over 5000 former patients, so Mary and her contemporaries are not entirely forgotten.

Endnotes

i With thanks to the staff of Florence Nightingale Museum, University of Edinburgh Heritage Collections, Edinburgh Central Library, National Library of Scotland, The British Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham, Bromley House Library, Nottingham, Lancashire Archives, Professor Lynn McDonald, University of Guelph, Canada, Dr Judith Godden, Australia.

ii Lancashire Archives, QAM/6/5/32/8508 Prestwich Asylum Medical Case book – Female, 31 May 1889- 31 December 1889.

iii The London Archives H91/ST/NTS//C/04/001 Nightingale Probationers’ Record Books Book A. Any details not separately referenced come from this volume.

iv Joshua Jebb, ‘Statement of the Appropriation of the Nightingale Fund’, Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (1863) p. 646.

v Agnes Ewart One of the founder members of the Manchester Nurse Training Institution.

vi National Archives Religious Census Returns 1851, HO 129/438-443 From the Return Just under 70% of church and chapel attenders in Nottingham were non-conformist.

vii Research on individual nurses by the author.

viii She was nursing in Cardiff when finally approved.

ix Lucy Seymer, Florence Nightingale’s nurses: the Nightingale Training School, 1860-1960 (London: Pitman, 1960); Monica Baly, Florence Nightingale and the nursing legacy (London: Whurr Publishers, 1997); Roy Wake, The Nightingale Training School 1860-1996 (London: Haggerston Press, 1998).

x Working with scalding water, fires, wet sheets, damp conditions hot irons and being on one’s feet for long hours: See Patricia E Malcolmson, Laundresses and the Laundry Trade in Victorian England, Victorian Studies 24/4 (1981), pp. 439-462

xi St Thomas’s moved to temporary accommodation at Surrey Gardens in October 1862 and to the new Hospital site in 1871: Frederick Parsons, Scenes from the life of St Thomas’s Hospital, from 1106 to the present time (Surrey: Redhill, 1937).

xii British Library, Add Mss 47729 f. 310 letter from Mrs Wardroper to Florence Nightingale 10 November 1867.

xiii British Library, Add Mss 47715 ff120-22 note from Florence Nightingale to Henry Bonham Carter 2 December 1867.

xiv British Library, Add Mss 47757 ff235-36v letter of Mary Barker to Nightingale 30 May 1868.

xv These no longer exist.

xvi Royal Commission into Public Charities 1873 Sydney New South Wales, Australia Witness: Mary Barker Questions 4600-4782

xvii British Library, Add Mss 47757 ff. 140-45 letter of Osburn to Nightingale May 12 1873.

xviii Anonymous, ‘The Robbery of brass from the Crewe Works’, The Nantwich Guardian, 2 October 1880.

xix Lancashire Archives, QAM/6/5/32/8508 Prestwich Asylum Medical Case book – Female, 31 May 1889- 31 December 1889.

xx London Archives, H1/ST/NC1/60/2 letter from Florence Nightingale to Mary Jones 15 May 1860.