Wendy Maddocks

Introduction

New Zealand was the first country in the world to register its nurses in 1901 and as New Zealand moved away from its colonial ties in 1907, nursing became a valued profession of educated women.[1] Prior to the Nurses Registration Act of 1901, nurses could be trained anywhere around New Zealand, in any hospital large or small. Once the Act came into being new nurses had to undergoing suitable instruction for ‘three consecutive years’ under a medical officer and a matron.[2] The state exams were marked by a doctor (the Registrar), and a commentary would be published in the Kai Tiaki New Zealand Nursing Journal (which was owned by Matron in Chief, Hester Maclean). In comparison, Great Britain registered its nurses in 1919, Australia started in 1920, with South Australia being the first state, while Canada started the process in 1908, with variances depending on the state or province.

As a Dominion New Zealand was obligated to provide support to Great Britain when war broke out in August 1914, and the request came for New Zealand to supply men, horses and guns. By the end of the war, New Zealand had provided the highest per capita contribution of troops, with 10 percent of the population (98,000) having served.[3] There has been significant analysis of the impact of service on soldiers after the First World War, which identified a shorter life span by eight years for those who had served the longest.[4]

Several authors have presented and described who the New Zealand nurses were, who served, and what they did.[5] Internationally work has been undertaken to understand more about the experiences of other commonwealth nurses and nurses from the USA. Some perspectives are also presented in a narrative review, and an indication of some of the extreme situations nurses were placed under have been explored from a UK perspective.[6] Several Australian scholars have presented work related to what happened to Australian nurses who served in the First World War touching on psychological trauma.[7]

What is missing from the English-speaking world is a detailed analysis of the experience of New Zealand nurses, placing their stories as distinct from the nurses of other Allied nations, and from returning soldiers. These women were pioneers in nursing in the true sense in that they were all registered to a national standard, which nurses from some other allied nations were not. None had any military training, but they were placed in situations of extreme risk and expected to conform to military protocols. Fortunately, the accessibility and completeness of the files retained for New Zealand’s nurses means it is possible to conduct a deeper interrogation into their experience.

To address this gap in the knowledge of the effects of war on New Zealand nurses, this study was undertaken in three parts to determine what impact service had on the type and amount of sickness, and lifespan, among members of the New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS) who had served overseas. Part one was an exploratory proof of concept pilot study of the first fifty (F 50) New Zealand nurses who served, as they had the longest service and were a distinct cohort. From this the second part of the study was conducted comparing the cohort of the F 50 with the last fifty (L 50) nurses who served for at least three months overseas before the Armistice. The final part then involved collating all of the information about all New Zealand nurses who served overseas, including sickness length, type, age of death and any other notable events (marriage, merit awards, or types of service for example).

A brief Historiography of Military Nursing in New Zealand leading to the Outbreak of the War (August 1914)

As a British Colony, New Zealand had sent troops to the Boer War, even though the country did not have a military medical or nursing corps at the time. It is believed that around thirty nurses from New Zealand served in South Africa between 1899-1901, and most went as private individuals paying their own way. A handful of nurses went as part of the Army Nursing Service Reserve and were able to identify themselves as New Zealanders with a silver fern on their uniform above their red cross arm bands. There is limited accessible information on what these nurses did or experienced.[8]

Based on the experiences of the nurses who went to the Boer War there was significant lobbying by Chief Nurse, Hester Maclean, to form a reservist Army Nursing Corps, which became possible with the 1908 Defence Act. A reservist force of nurses was to be assembled under the command of the newly formed New Zealand Medical Corps (NZMC).[9] This was in recognition of the emerging political tensions in Europe and New Zealand’s new status as a self-governing Dominion, in 1907.[10] However, this was not yet a military nursing corps and there was no military training of nurses undertaken between 1908 and 1914.

When War was declared in August 1914, New Zealand quickly mobilised its resources as instructed by the British Government. Despite almost 400 nurses registering their willingness to serve, the New Zealand government was told by its British counterparts that New Zealand nurses would not be needed.[11] The tone in official documents implied that it was impertinent of New Zealand to offer, meaning that Britain could supply enough nurses without assistance from its Dominions. Whilst at least nine women were sent to Britain officially to support, they were not allowed to be considered as New Zealand nurses (i.e. they could not wear their medal).[12]

A hastily collated group of six nurses was also sent with troops as part of the NZMC in early August to what was then German-held Samoa. The nurses were chosen pragmatically based on their proximity to Wellington, from where they were to sail, and had three days’ notice to prepare themselves; uniforms were quickly made. The nurses looked after the troops on the passage to Samoa, including inoculations, first aid, and other care to prepare for life in the tropics. Once in Samoa they cared for the local population and were initially supported by the surrendered German medical and nursing staff until their return to Germany.[13]These nurses stayed until they were sent onto Europe, and other nurses rotated through to Samoa.

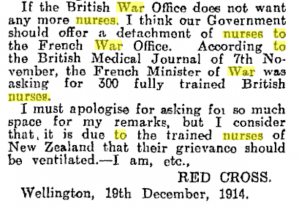

Despite the attitude of the British government, possibly dozens left privately to sign up with Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), the newly formed Red Cross, The Order of St John, and some also served with French and Serbian units as they were already in Europe. A newspaper article reprinted in New Zealand in October 1914, from the United Kingdom’s Nursing Times, published a list of the five approved organisations which trained nurses could apply for and noted that for those nurses from ‘the colonies who wanted to go Home,’ it was the ’best chance they would get to go to the front.’[14] By October 1914, at least twenty two New Zealand nurses had registered with the War Office in London, offering their services. An anonymous letter in the Kai Tiaki journal also noted that if Britain did not want New Zealand nurses, then France certainly did!

[Fig. 1] Screenshot by author from Papers Past which is a typical entry published in all newspapers: Evening Post 22 December 1914.

These anonymous letters were common and are believed to have been written by Hester Maclean as part of her political lobbying to have nurses go to war, as some of the content was very well-informed.

In early 1915, the planning to seize control of the Dardanelles was well under way with the inclusion of thousands of Allied troops to provide the necessary manpower. The New Zealand government finally relented, realising it needed to support the country’s troops with nurses, given the high casualty rates expected. In addition, letters were being received by nurses and families from those early nurses talking about the great need, and conditions they worked under. Many expressed concern at the unnecessary deaths of the wounded due to lack of good nursing care on the basis that ‘Arabs’ (and medical orderlies) did not know how to nurse (as written by an anonymous nurse at the time).[15] What this nurse meant was that due to the religious beliefs of local carers, patients were not consistently nursed after sundown (i.e. fed, turned or given wound care) so were succumbing to preventable infections.

The New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS) was gazetted 31 March 1915, and fifty nurses were handpicked by Hester MacLean from the list of 400 who had volunteered. A few short days later, these nurses sailed to the unknown, having signed the same attestation papers which all NZ Expeditionary Forces (NZEF) signed, confirming them as being part of the New Zealand Army. This gave the women a service number, and they signed up for the duration. They had no idea where they would be going, apart from the initial destination of England.

The nurses had to be registered with six years of experience (registration was obtained at age twenty three), to be aged under forty five, and Pākehā (i.e. non-Māori). This latter constraint should not be considered a racist or exclusionary decision, as at the time there was probably only a dozen Māori nurses who were registered (most hospitals trained one or two a year). Hester Maclean did not want to take the nurses from their own communities, where there was great need, due to the ravages of typhoid at that time. It was not expressly stated that the nurses needed to be unmarried, which meant that some who married later on during service could stay working, at least until they returned home.[16] According to the files reviewed for this project, at least one married nurse returned home due to pregnancy but was required to be on light duties on the ship back (meaning the Army would not pay for an indulgence passage), and another nurse attested and got her passage to England, only to get married on arrival and promptly resign!

Local communities rallied around ‘their nurses,’ holding tea parties and giving practical gifts such as deck chairs, writing cases and hip flasks. These events were widely reported on in local newspapers. The nurses converged from around the country and had a few days together in Wellington, where they were issued with their uniforms (winter and summer), and met the Prime Minister. They were photographed on the steps of parliament and attended several dinners. Bonds were quickly made, and friends and family also travelled to see them off on the SS Rotorua on 8 April 1915, which sailed also carrying troops and civilian passengers. The first indication of some of the poor treatment that these nurses could expect was their being issued second-class cabins even though, as officers, they were entitled to be accommodated in first class. The Defence Department claimed first class was too expensive. One nurse (Mabel Crook) wrote in her diary of the sadness she felt, as the ship sailed out of Wellington Harbour, when it stopped a short way out and the passengers were advised that a launch was coming to pick up any last-minute post cards and drop off mail to the boat.[17]

Phase One and Two Interrogation of Data

The starting point for data collection for this project was a data base created for the anniversary of the Gallipoli landings in 2015, which gave a list of names and service numbers of all New Zealand nurses who served in the First World War.[18] This list contains over 600 names and each was searched for on the New Zealand Archives online data base.[19] This allowed for statistical analysis of data sets by year, by service, by illness and other parameters. Further statistical analysis was conducted once data sets were inserted into the SPSS programme.

Phase One Pilot Study

The F 50 nurses were part of a unique cohort of nurses who, upon arrival in England, were sent to a number of locations in France, Egypt or hospital ships. An analysis of the medical and service files of these fifty nurses found that they did have a shorter life span compared to the normal female population in New Zealand. In addition, many of the nurses experienced a number of serious illnesses related to fatigue, exhaustion, neuritis, and over work as documented in many files. All of these nurses did return to New Zealand at the end of their service and were older at attestation (mean age of thirty four) and more experienced (mean 5.46 years; range, three to eleven years) than later cohorts. When they commenced service, they had no idea at the time how long they would be away, and given the length of the war it is not surprising they served overseas the longest of all the New Zealand nursing cohorts, with a mean length of service of three years and 170 days (range two years – five years sixty six days). Ten percent of these nurses were invalided home after serious illness. Most nurses had more than one illness and many such complaints were of an infectious nature such as enteric fever, gastritis, and tuberculosis (TB), which diagnoses related to the harsh conditions in which many of them were working.[20]

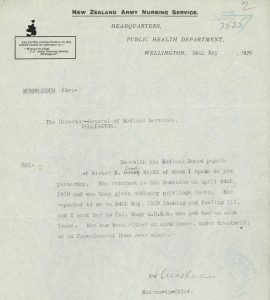

One nurse from the F 50 cohort has a story which is indicative of how ill some of the nurses had become and the poor welfare provisions for them once they returned back to New Zealand. Sister Mabel Crook’s diary and papers have been transcribed by the author and this story has been published.[21] After periods of convalescence, she sustained a back injury and when she eventually returned to New Zealand in 1919, she had to work the passage on light duties, even though her medical board had recognized that she was an invalid at the time. This letter from Matron in Chief Maclean about Sister Mabel Crook is indicative of the serious illnesses the nurses experienced.

[Fig 2] Letter in file of Sister Mabel Crook, screenshot by the author: Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, Wellington, AABK 18805 W5553 030263 R21899194.

Her initial diagnosis changed from neuritis (related to the back injury) to neurasthenia. As soon as she arrived in New Zealand she went back to her hometown of Palmerston North. From there, she was sent to the military rehabilitation centre in Rotorua for treatment, but this did not go well. Due to poor planning and little consideration of the need for welfare for the exhausted nurses, there were no female beds. Mabel had to pay for private board and lodging (as did several other nurses) and travel for daily treatment which went on for months.

[Fig. 3] Screen shot from online file of nurse taken by author as an example of types of communication: Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, Wellington, AABK 18805 W5964 0361419 R24207677.

This is a typical example of correspondence in many nurses’ files, where Matron Maclean advocated for her nurses, and protested about the injustice of their care. Crook’s file is testimony to the inefficiencies in the system, with communication about payment and the duty sergeant refusing entry until the bill was paid. After several months Crook was sent to Hanmer Springs hospital in the South Island, where the more serious psychological cases went. Despite being ill, she was sent there to work light duties so she could stay in the nurses’ home. This journey involved a train ride for several hours, an overnight ferry, another train ride then a taxi to the remote hospital, nestled beside some hot springs in the mountains. This journey would have taken almost three days. When she presented herself, luckily the presiding medical officer could see was ill, immediately diagnosed her with hysteria, and admitted her (even though, again, there were no female beds). The paper wars continued for Mabel and multiple telegrams and letters in her files show that no one wanted to take the blame for the mismanagement of Mabel’s care. In the end the Army blamed the post office for ‘mangling the telegram to read “outpatient” instead of “in patient” care’. Mabel’s family reports that she stayed at Hanmer Springs for at least two years and that as an old women she had a permanent tremor (which they attributed to the stresses of her overseas service). Mabel’s battle for justice continued for another fifty years: for example, she applied to go to the fiftieth anniversary commemoration of the Gallipoli landings. She had worked there from July 1915 on a British hospital ship and had even been sniped by a Turkish bullet. The Army refused to believe she had been there, even though her service was well-documented. She had been put forward for an award for bravery by the command of the HMHS Nevasa (the British Hospital Ship she was posted to), which she had refused at the time. Eventually she got the Gallipoli anniversary medal and was allowed to accompany the veterans. She was the only New Zealand nurse who did so.

Below is a proud Mabel wearing her medals in 1965 as she made the journey to Gallipoli for the commemorations. She won that battle for recognition.

[Fig. 4] A photograph taken by author from the collection of papers of Sister Crook at the National Army Museum, Waiouru, NZ, accession number 2001.277.

Phase Two

Based on the findings of the pilot study, a comparison was made with the last fifty nurses who had served overseas for at least three months, to explore if there were any differences in length of sickness and age of death. This study has been reported in full elsewhere and is not repeated here; however, the results suggested there were statistically significant differences between the two cohorts, and that it was therefore worthwhile to undertake the full analysis of all 600 files.[22]

Full Study Data Analysis

Using the 600 names on the NZANS website as a starting point, all digital files were downloaded and reviewed.[23]

Data verification

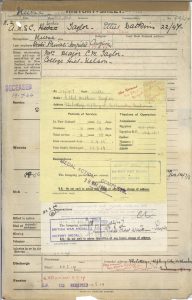

Data from the service files was cross checked with the Nursing Register, the online cenotaph, and census records. [24] Only nurses who had service with the NZANS were included as reliable files did not exist for New Zealand nurses who had served with other agencies. In addition, two surviving volumes of the original NZANS register 1916-1917 and 1917-1919 were viewed in person after all the files had been downloaded to ensure there were no missing names.[25] A new data base was created and populated with all the details mentioned in the introduction (where available). If a date of death (DOD) was not documented in the military file, further searching through Ancestry and online death records/cemetery records was undertaken and compared with newspapers for obituaries. Results from Ancestry were only used if these could be verified as belonging to the nurse, such as through the picture of a headstone or mention of their war service and there were at least two incorrect entries identified on Ancestry.[26]. Multiple errors were found in the files, and many names were removed from the first draft of the data base. Reasons for these edits included not being registered or not serving for the NZANS. Some nurses had duplicate files, and some had misspelt names or files had even been mixed up with those of soldiers with similar names. Most files had a cover sheet where information for the nurse was summarised (see Figure 5). Typically, this showed service length and location, medals, any sickness, and death.

Once all this information was obtained and cross checked it was possible to use the Excel spreadsheet to make calculations, and tabs were created for each year, the F 50, the L50, the entire cohort, and a separate tab for the twenty-eight nurses who survived the sinking of the Marquette ship. The Marquette contained the No 1 New Zealand Stationary Hospital and was torpedoed off Salonika 23 October 1915. Ten nurses lost their lives along with other troops and crew. Given their unique experiences of being in the water for hours, and the serious injuries the nurses sustained, it was worthwhile exploring them as a separate cohort.[27]

[Fig. 5] Photograph of front page of NZANS file held online showing the summary of service sheet, screen shot by author: Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga, Wellington, AABK 18805 W5553 0112307 R7824200.

Results

Six hundred and twenty nurses were confirmed as serving for the NZANS between April 1914 and January 1920; however, the analysis offered here relates to the 543 who had confirmed overseas service which commenced before 11 November 1918. This number includes the seven who left for Samoa, even though they were not NZANS at the time, as they all went on to serve overseas as part of the NZANS. The figure of 543 women accounted for just over 20 percent of the total registered nursing workforce based on the 1918 register of nurses.[28] Soon after the first fifty were sent another 205 were sent in 1915, with most going to either Egypt or to work on hospital ships. When the Gallipoli campaign was over later in 1915, most nurses were then sent to work on the Western Front in stationary hospitals, general hospitals, casualty clearing stations, hospital trains or on the ships taking the wounded back to England.[29] A handful trained as nurse anaesthetists and one or two are recorded as working in regimental aid posts very close to the fighting.[30]

Some nurses also had New Zealand service recorded in their files, and this would have either been spent getting ready for sailing or working in the military hospital after their return. This figure would have also included any time they were in hospital in New Zealand as patients.

All hospital ship work or working on their return passage was counted as overseas work. Service was calculated manually from information in some files, and it was contained in the front of the file as a summary in others. Table 1 shows emphatically the higher burden of service the 1915/16 nurses experienced compared with later cohorts, serving in multiple theatres as the war evolved on different fronts. In contrast those nurses who started their service in 1917 onwards were primarily on hospital ships or in English hospitals, mostly away from danger or from extreme working conditions. Most of the 1915-1916 nurses served in at least two locations, for example moving from hospital ship work in the Dardanelles, to Egyptian hospitals to the Western Front, and then onto New Zealand general hospitals in Britain. Table 1 summarises the key findings from the files, based on each year service began. The focus is on longevity, sickness burden (represented through time off sick) and disability (through being invalided home).

Table 1: Mean of each variable across each year of war NZANS served

| N=543* | 1915

(n=263) |

1916

(n=130) |

1917

(n=56) |

1918

(n=94) |

|

| Mean age at service years | 32.4 | 32.7 | 33 | 32.1 | 32.2 |

| Mean total service days | 1719 | 1287 | 1017 | 860 | 718 |

| Mean time overseas days | 1371 | 1036 | 807.6 | 527 | 543 |

| Service Egypt (% of total) | 265

(48%) |

206

(78%) |

49

(29.5%) |

5

(8.9%) |

5

(5.3%) |

| Western Front (France & Belgium) | 93

(16.9%) |

35

(13.3%) |

54

(41.5%) |

4

(7.1%) |

0

(0%) |

| Hospital Ships (including back to NZ) | 181

(32.9%) |

77

(29.2%) |

37

(28.4%) |

28

(50%) |

39

(20.7%) |

| UK Hospitals | 118

(21.5%) |

41

(15.6%) |

27

(20.7%) |

10

(17.8%) |

40

(42%) |

| Mean calculated sick days | 72.5

(1-1095) |

77

(1-719) |

85.1

(1-1095) |

50.2

(1-616) |

37.8

(1-212) |

| %of service sick | 6.8% | 5.99% | 8.37% | 5.83% | 5.2% |

| % of nurses sick | 64%

(n=341) |

68.4% (n=180) | 53.84%

(n=70) |

53.5%

(n=30) |

43.6%

(n=41) |

| Invalided to NZ

(% of sick nurses) |

65

(11.8%) |

40

(15.2%) |

19

(14.6%) |

2

(6.6%) |

1

(2.32%) |

| Mean Age at Death

(Life expectancy 76yr) |

76.2

(n=499) |

75.12 (n=234) | 76.2

(n=114) |

78.1

(n=44) |

76.3

(n=130) |

| % of nurses who died before aged 76 | 16.8 | 36.7 | 39.5 | 29.5 | 23 |

* Note this figure includes the seven nurses who started in 1914 as they went on to serve overseas.

Age and Experience in Service

In New Zealand at the time, sitting State Exams occurred after three years of training. The earliest age a nurse could theoretically sit their State Exams was twenty-one. Medals were not issued, however, until the age of twenty-three, so it was usual for nurses to work as staff nurses once qualified, but not be paid as such until they achieved their medals. As the requirement was for nurses to have six years of experience before recruitment to NZANS, the youngest possible age was theoretically twenty-seven, and the oldest forty-five. However, it is clear this was not strictly followed. The calculated average confirmed age of 32.4 years was found to be higher than was calculated elsewhere.[31] Two nurses attested and served aged twenty one, and their dates of birth were cross checked. It is possible they were registered, as medals were not issued until aged twenty three, but nurses could sit their exams beforehand. They both attested in 1916, so even a possible relaxation of rules at the end of war cannot account for this low age. Six nurses were older than the required forty-five, with the oldest being fifty-eight. As the war went on, the serving nurses became younger and less experienced. There was, perhaps surprisingly, no correlation between age and experience and length of service. Forty two percent of the nurses had two fewer years of post-registration experience than they were supposed to have, and of these eight attested as soon as they registered, later in 1915

Sickness

In total 341 nurses (62.8 percent) had documented sickness in their files, and this was either stated on the casualty form, or evidence from medical boards was present. Not all files had sickness records: however, this does not mean the nurses were not sick, therefore any calculations about sickness rates can be considered conservative. Only one file held a remnant of clinical notes with a temperature, pulse, and respiration (TPR) chart and half a page of medical notes. Periods of sickness included prescribed convalescence, with the 1915/16 nurses having the greatest burden of time sick and being invalided home, compared to the 1917/18 nurses. Whilst the term shellshock was applied to soldiers early in the war (1915-1916), and was believed to be specifically related to the noise of the guns, this term was not used in any of the nurses’ files. The way shell shock was to be recorded in medical files changed in 1916 in New Zealand, and it had to be noted whether it was experienced with a wound (w) or with sickness (s).[32] The alternative terms like debility or exhaustion were also used and these usually followed a diagnosis of infectious illness. Of the nurses who had sickness, twenty four percent were also prescribed convalescence in one of the locations provided to convalesce, which ranged from a houseboat in Egypt, to comfortable homes in Brighton and Sandwich. Whilst the severity and type of illness experienced in each year was higher in the 1915/16 cohort compared to later years, there was no statistical difference in the percentage of time being sick.

The 1916/17 influenza epidemics, which started in the huge Étaples barracks and hospital in France, took their toll on New Zealand nurses, with 100 having documented illnesses related to influenza during this time, compared to eighteen in the 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak.[33] However, the 1918 outbreak, named ‘Spanish Flu’, was more deadly, taking the life of one New Zealand nurse, along with at least eighty soldiers, who were on the so-called ‘Death Ship Tahiti’ in August 1918. There had already been two waves of influenza earlier in 1918, which had not reached New Zealand, so troops and nurses travelling to Europe did not have any immunity to this outbreak. The virus was acquired when the ship stopped in Sierra Leone for restocking. The New Zealanders were not allowed to leave the ship as the command was aware there was an influenza outbreak. It either came on board via locals supplying the ship, or radio operators who had attended a meeting on the HMS London (which had left London where influenza was rife). Within a day of leaving port, influenza started on the Tahiti, eventually affecting ninety percent of those on board (1100 people). The overcrowded conditions were a key factor in transmission.[34] Letters from nurses on board described the horrendous conditions, with boys dying in front of them within hours, having to step over bodies to get to the living, and trying to care for patients in the high bunks. There had been one nurse on board to care for the 600 troops, and ten passenger nurses, which contingent the Captain of the Tahiti had previously called frivolous. This disaster was not the end of the impact of influenza for New Zealand nurses, however, as large victory parades with returning troops in November spread the disease through local populations. It cost the lives of at least thirty nurses, some of whom had returned from war only to be straight back into providing care for the local population.[35] These nurses are not included in the analysis as influenza in this instance occurred after the end of the war among non-NZANS personnel.

Marquette Survivors

The sinking of the Marquette on 23 October 1915 claimed the lives of ten nurses, and the remaining twenty-six who survived had a prolonged rescue, causing hypothermia, exhaustion and injuries with some serious individual effects.[36] Ten of these nurses were invalided back to New Zealand, but most returned to serve overseas in 1916, with an average overseas service of 1033 days. After the initial period of five days recuperating in Salonika, their level of sickness was no higher overall that other nurses, equivalent to six percent of their total service, with an average overseas service of 1033 days. Two nurses had severe injuries which crippled them for life, and the remaining nurses all developed illness such as influenza, or rheumatism.

Injuries

Apart from the Marquette sinking, a handful of nurses were injured whilst serving. Once nurse fell and broke her arm but carried on caring for patients (before seeking treatment for herself) due to a big rush. Some slipped on decks or ice, one sustained a serious head injury at a train station, and one lost an eye (but was able to resume work in New Zealand after a period of recovery). As mentioned previously with Sister Mabel Crook, often these injuries appeared to become the precursor to a more debilitating diagnoses of neurasthenia and hysteria. For comparison, these terms were not found in any files of nurses who served from 1917 onwards.

Death on or due to service

Thirteen NZANS lost their lives in service, ten of whom were on the Marquette.[37] This ship’s sinking occasioned New Zealand’s greatest loss of nursing life in war. Others died through complications of illness, including Nurse Tubman who died of influenza from being on the SS Tahiti, and another who died of enteric fever in 1915 in Egypt. In addition to these thirteen, at least two other New Zealand nurses died whilst serving for other countries. One was shelled in Belgium, and one died in Cairo after being hit by a tram. Three other nurses who died within ten years after the war have recorded in their files ‘death due to war service’ and these were from complications relating to tuberculosis and liver/kidney failure. For this latter nurse, her obituary notes that she had been sick for five years and that her death ‘was due to hardships of war;’ her file notes ‘toxaemia.’[38] Three files of nurses who had an earlier-than-expected age of death (<60) contained the notation ‘died of sickness, death not due to military service.’ This was important if any war pensions were due to families.

No incidents of death by suicide during service were found in the files, or in any newspaper reports. This event was freely reported in the newspaper and at least four records of New Zealand soldiers committing suicide on service were found.[39] However, whilst searching newspaper archives, two cases of suicide years after the war were found related to nurses who had served in the First World War. The first nurse had not been able to work after her return from service and was known to be depressed. One day she did not return from her usual morning swim. Her body was found by her sister and the coroner recorded her death as suicide.[40] The second is a little more unusual, as the nurse involved only had a very short service at the end of the war repatriating soldiers. It is unlikely her tragic end was related to any residual stress from war, as it occurred almost twenty years later. She was an accomplished pilot (one of the first women to be so qualified) and worked as a theatre sister. In 1937 she was a passenger in a small airplane crossing from the South Island of New Zealand to the North Island when she simply opened the door of the plane and jumped out over the ocean. There was no inquest as there was no body, and no record even of her birth. The pilot did not think it was an accident as she actively jumped from the plane, despite him trying to stop her.[41]Given the mixed way of reporting or recording of suicide by other countries, it is not possible to identify if these New Zealand experiences are comparable to nurses serving for other allied countries.

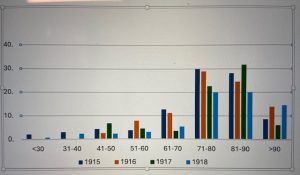

Life Expectancy and Marriage

The life expectancy for women born in New Zealand in 1886 (the closest data collection point for comparison), who lived beyond the age of five, was seventy-six years.[42] Date of death was confirmed for 499 of the NZANS nurses. The mean age of death for all nurses was similar to the expected life expectancy; however the 1915/1916 nurses had a higher number of nurses who died younger (partially due to the ten who were killed on the Marquette). To further highlight the differences between each of the year cohorts and their age at death, calculations were made comparing percentages of nurses who had died at each age range. This is presented visually in graph 1. This further reinforces the finding that the burden of earlier-than-expected death was higher in the 1915 cohort. The 1916/1918 cohorts had more nurses living past 91 years.

Graph 1. Percentage of nurses from each year who died in each age range

Unlike other allied countries, New Zealand did not expressly forbid its serving nurses from getting married, and if they chose to, they could carry on working while overseas. However, they were expected to resign on their return, but a small handful did remain on the reserve list. Around forty percent of all serving nurses did get married and this had no statistical effect on their rate of sickness, their lifespan, or length of service overall. These calculations were done to see if perhaps there were pregnancies, recorded as ‘sicknesses’, or leaving service for marriage. As mentioned earlier, the New Zealand nurses could remain on overseas service if they got married, but once they returned to New Zealand they were meant to resign from the army (but could still nurse).

Conclusion

This analysis of the 543 files of nurses who had confirmed overseas service commencing at least three months prior to 11 November 1918 has highlighted that, for many, the impact of their service was severe. Furthermore, the burden of war service for the NZANS was greater than that shown by the statistics. It would be unthinkable now to send personnel to an overseas deployment for years, without returning home. The information obtained from this analysis shows that where information exists, the nurses were overworked, exposed to risk in the form of injury, disease or even death. There was no preparation made by the government, in consideration that these returning nurses would need any special care apart from a short break after their return, and nurses relied on each other and on their families for prolonged care.

Nurses were entitled to the same twenty-eight days leave as the soldiers received, yet most had to return straight back to work with the influenza pandemic of 1918. Matron Maclean met every returning ship and described her nurses as ‘worn out,’ ‘broken’ or ‘done in’. The mental toll of working in unrelenting conditions, caring for thousands of patients, and being away from family, did have an impact as is illustrated by the diagnoses of ‘hysteria’ for some. More than half of the first fifty nurses received awards or commendations for their service, whereas none in the 1918 cohort did. This is another indication of the extreme conditions they were exposed to. Whilst there are a number of narrative accounts from nurses of wonderful times, such as visiting pyramids, Pompeii, sightseeing, and champagne suppers the bits in between, or the gaps in the diaries, are all important.[43] The Matron in Chief, knew what her nurses needed, but her battles for fair treatment, in their medical care, provision of pensions, and places for nurses to rest, were a constant part of her work – and the nurses knew this. There are letters in the archives from grateful nurses writing to her thanking her for looking out for them. This image from the autograph album of Sister Mabel Crook, shows some of the sentiment patients felt towards nurses.

[Fig. 6] Photo taken by author from Mabel Crook’s autograph album. Original held in the National Army Archives, Waiouru, New Zealand Accession Number 2001.227.

Whilst Mabel’s story is extreme, she was not the only nurse to be treated so poorly on her return. Multiple files show further examples of mistreatment such as battles over pensions; arguments about the relation of disability to the war; refusal by the army to pay for medical care anywhere; and nurses having to walk to hospitals (in the absence of transport provided by the army) even though they were sick. At least one nurse with active TB had to walk to the Christchurch sanatorium from the train station. Another nurse had 40 pieces of correspondence in her file about paying to send her trunk by train to her hometown. Soldiers’ possessions were sent all the way home, but if nurses had too much luggage the army would not pay for anything extra. This particular nurse had also been away for five years. Nurse leaders knew their nurses needed care and provided convalescent homes for returning nurses, yet Matron in Chief Maclean was not allowed to view their medical boards. She continued battling for this access and it was finally granted in 1921. It is clear that this omission of Maclean from the decision-making process affected the provision of care for the nurses

A final insult for nurses was that for the annual Anzac Day and Remembrance Parades, nurses were either left out the official parties, not allowed to parade, or made to sit at the back behind other dignitaries.

Whilst the hypothesis of a lower age of death for the nurses who served from 1915 could not be supported by the data from this project, the burden of illness was notably higher in the 1915/16 nurses, with longer times spent being sick. The lack of provision for welfare and physical care on their return is an indictment of the government of the day. For those ill and invalided nurses, the price they paid for their service was too high.

Endnotes

[1] New Zealand Acts as Enabled (n.d.) Available at: http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/nra19011ev1901n12347/ [accessed 20 January 2022]; New Zealand History (n.d.). Available at: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/dominion-day [accessed 14 August 2023].

[2] New Zealand Acts As Enacted (n.d.) Nurses Registration Act 1901 [online]. Available at: http://www.nzlii.org/NZ/legis/hist_act/nra19011ev1901n12347/ [accessed 2 June 2023].

[3] New Zealand Expeditionary Forces Provisions and Maintenance 1914-1918. Available at: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/sites/default/files/documents/ww1-stats/provision-and-maintenance.pdf [accessed 1 August 2022].

John Horrocks, ‘The limits of endurance: Shell shock and dissent in World War One’, Journal of New Zealand Studies 27 (2018), 35-49. https://doi.org/10.26686/jnzs.v0iNS27.5175; Nick Wilson, George Thomson, Jennifer A. Summers, Glyn Harper, John Horrocks, and Evan Roberts. ‘The health impacts of the First World War on New Zealand: a summary and a remaining research agenda’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42/6 (2018), 516-518; Nick Wilson, Christine Clement, Jennifer A. Summers, and Glyn Harper, ‘Mortality of first world war military personnel: Comparison of two military cohorts,’ British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.) (2014).

[5] Anna Rogers, With Them Through Hell New Zealand Medical Services in the First World War (Auckland: Massey University Press, 2018); Sherayl McNabb, 100 Years New Zealand Military Nursing 1915-2015,(Wairoa, New Zealand: Sheryal McNabb, 2015).

[6] Christine Hallett, ‘Portrayals of suffering: perceptions of trauma in the writings of First World War nurses and volunteers’, Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 27/1 (2010), 65-84; Kayla Kampana, ‘Sacrificing Sisters: Nurses’ Psychological Trauma from the First World War 1914-1918’ (unpublished Masters thesis, University of Central Florida, 2022). Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/983/; Rohini Bhardwaj, ‘Nursing in the War crisis: A narrative review’, Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies 9/2 (2022); Amanda Gwinnup, ‘Hazards of Nursing During the First World War, 1914-1918’, The Bulletin, 11 (2023). Available at: https://bulletin.ukahn.org/hazards-of-nursing-during-the-first-world-war-1914-1918/

[7] Kirsty Harris, ‘New horizons: Australian nurses at work in World War I.’ Endeavour 38/2 (2014), 111-121; Margaret Doherty, ‘Life After War: The Ongoing Contributions of Queensland’s First World Nurses After the War’, (unpublished Masters thesis, University of New England, 2022). Available at: https://rune.une.edu.au/web/handle/1959.11/53267; New Zealand History (n.d.). Available at: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/new-zealand-in-the-south-african-boer-war/women [accessed 14 October 2024].

[8]Anna Rogers, While You Were Away: New Zealand Nurses at War 1899-1948 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2004).

[9] Anonymous, ‘New Zealand Medical Corps Nursing Service Reserve,’ Kai Tiaki: The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, 1/4 (1908), 110. Available at: Papers past https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19081001.2.19 [accessed 2 June 2023]; McNabb, 100 Years. New Zealand Acts as Enabled (n.d.) Defence Act 1909 [online]. Available at: https://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_act/da19099ev1909n28149/ [accessed 2 June 2023].

[10] New Zealand History (n.d.). Available at: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/dominion-day [accessed 1 October 2024].

[11] Anonymous, ‘Nurses Anxious to Serve’, Evening Post, 22 December 1914, 3. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19141222.2.21.1 [accessed 2 June 2023].

[12] McNabb, 100 years.

[13] Anonymous, ‘Our First Nurses for the War’, Kai Tiaki: The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, VII, 4 October, 1914, 157. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19141001.2.14.4 [accessed 2 June 2023]; McNabb, 100 Years. Alexander Turnbull Library Wellington, New Zealand, MS-Papers-2023, Papers of Sister Ida Willis, 1915-1968. Ida Willis, OBE, served as a nurse in the First World War and became Director, NZ Army Nursing Service, 1936-1946. Available at:

https://tiaki.natlib.govt.nz/#details=ecatalogue.11447, viewed in person, January 2024.

[14] Anonymous, ‘Nurses for Military and Naval Service,’ Kai Tiaki: The Journal of the Nurses of NewZealand, 1 October 1914, 176. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19141001.2.28 [accessed 2 June 2023].

[15] Anonymous, ‘Active Service’, Kai Tiaki : the journal of the nurses of New Zealand, 1 January 1915, 13. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/KT19150101.2.12 [accessed 2 June 2023].

[16] McNabb, 100 Years.

[17] Wendy Maddocks, Broken Nurse of the Great War the Annotated Diary of Sister Mabel Crook(Christchurch: Wendy Maddocks, 2024).

[18] This website was www.nzans.org; however at time of writing this site has been archived following the death of the creator. It is currently archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20230126100532/https://www.nzans.org/ (as at 20 October 2024). There are plans for the site to be hosted by a Government agency given the historical significance of the data it contains.

[19] www.archives.govt.nz contains all digitised files of the First World War serving personnel. Each file was downloaded, reviewed, and cross checked. Missing information such as date of death was searched for using Ancestry records, online obituaries and cemetery records. In some case a will existed online, which also was used to verify date of death. Information collated includes service type, length, illness, service length, experience, sickness length and type and any other notable events including medals. All other individual data relating to nurses which is not referenced can be found in the digitized files.

[20]Wendy Maddocks, ‘Too Sick for Caring? An Analysis of the Health Impact of the Great War (1914-1918) on The First Cohort of New Zealand Nurses Who Served’, Journal of Military and Veterans Health, 31/2 (2023), 56-64.

[21] Maddocks, A Broken Nurse.

[22] Wendy Maddocks, ‘Broken Nurses: An Interrogation of the Impact of the Great War (1914–1918) on the Health of New Zealand Nurses who Served – A Cohort Comparison Study’, BMJ Military Health (2023).

[23] The paper copies are protected and not accessible; however in preparation for the 100-year anniversary of the First World War, the New Zealand Government, funded various projects through different agencies including the extensive volume 100 years of New Zealand Military Nursing 1915-2015, by McNabb. She was given permission to access the original records and collated a data base with the names and details of all nurses who served. [www.nzans.org Ibid.] Available at: www.archives.govt.nz

[24] Supplement to the New Zealand Gazette (1918), Register of Nurses. Available at: https://www.nzlii.org/nz/other/nz_gazette/1918/32.pdf [accessed 2 June 2023].

[25] National Archives Wellington, NZ, Accession number R26083492, 1st New Zealand General Hospital – Register of New Zealand Army Nursing Service [NZANS] Staff – May 1917 – March 1919.

[26] Due to the cost involved death certificates were not sourced. Another person cross checked a sample of files, and copies were made of each spreadsheet and stored elsewhere for security.

[27] Ministry for Culture and Heritage (n.d.), New Zealand nurses lost in Marquette sinking 23 October 1915.Available at: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/page/new-zealand-nurses-lost-in-marquette-sinking [accessed 17 August 2022]; Anna Rogers, No ordinary Transport: The Sinking of the Marquette (2019). Available at: https://ww100.govt.nz/no-ordinary-transport-the-sinking-of-the-marquette [accessed 17 August 2022].

[28] Supplement to the New Zealand Gazette, (1918).

[29] Anna Rogers, With Them Through Hell New Zealand Medical Services in the First World War. (Auckland: Massey University Press, 2018).

[30] Wendy Maddocks, ‘Nurse Anaesthetists in the first World War,’ Salient Points, (May 2023), 63-67.

[31] Rogers, With Them Through Hell.

[32] Rogers, With Them Through Hell.

[33] J.S. Oxford, A. Sefton, R. Jackson, W. Innes, R.S. Daniels, & N.P Johnson. ‘Early Herald Wave Outbreaks of Influenza in 1916 Prior to the Pandemic of 1918’, International Congress Series, 1219 (2001), 155-161; J.S. Oxford, A. Sefton, R. Jackson, W. Innes, R.S. Daniels, and N.P. Johnson, ‘World War I May Have Allowed the Emergence of “Spanish” Influenza’, Lancet Infect Dis, 2/2 (2002), 111-114.

[34] Ryan McLane, ‘Influenza on the SS Tahiti’ (2018). Available at: https://ww100.govt.nz/influenza-on-the-ss-tahiti [accessed 10 January 2024].

[35] Christchurch Nurses Memorial Chapel. Available at: https://www.cnmc.org.nz/the-chapel/influenza-epidemic/ [accessed 20 March 2023].

[36] Rogers, No Ordinary Transport.

[37] Rogers, No Ordinary Transport.

[38] ‘Roll Of Honour’, Kawhia Settler and Raglan Advertiser, 30 November 1928, 3. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/KSRA19281130.2.15 [accessed 1 April 2023].

[39] N. Wilson, J. Summers, M. Baker, G. Thomson, and G. Harper, ‘Fatal injury epidemiology among the New Zealand military forces in the First World War’, New Zealand medical journal 126/1385 (2013), 13-25. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24217587/; Wendy Maddocks, ‘Soldier Suicides’, Salient Points, (August 2022), 64-64.

[40] Anonymous, ‘Nurse Found Drowned’, Sun (Auckland), 21 May 1927, 14. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/SUNAK19270521.2.121 [accessed 1 June 2023].

[41] Stuff. Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/6390366/Curious-case-still-a-mystery [accessed 14 March 2023].

[42] Statistics New Zealand (n.d.). A History of Survival in New Zealand: cohort life tables 1876-2004 (page 47). Available at: https://statsnz.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p20045coll1/id/564 [accessed 20 June 2022].

[43] Hannah Clark, ‘Sisters in a distant land: the exploration of identity and travel through three New Zealand nurses’ diaries from the Great War’, Women’s Studies Journal, 30/1 (2016), 17-29. Available at: https://www.wsanz.org.nz/journal/docs/WSJNZ301Clark17-29.pdf [accessed 20 June 2022].