Stuart Wildman

Introduction

The First World War was different to the conflicts in which Britain had traditionally been engaged. It was the first total war in which the entire population was involved. It also affected Britain directly, in the form of enemy bombardment from the sea and air, and from the attempted blockade of imports of food and other goods by the German U-Boat fleet. All strata of society were affected by and participated in the war in terms of work and voluntary service. Between 1914 and 1918, over two and a half million sick and injured men were repatriated and cared for in a variety of hospitals within the United Kingdom.[1] The appropriation of hospital beds, entire hospitals, asylums or workhouses, and the recruitment of large numbers of trained nurses and doctors to care for these servicemen, had a significant effect on the health services offered to the civilian population.

This is a topic that has received little attention from historians and particularly historians of nursing. The actions of nurses in theatres of war, the conflict between professionals and volunteers, the establishment of the College of Nursing and the moves towards registration during the war have all been covered.[2]However, the nursing of the civilian population has largely been forgotten as attention has been focused upon those who cared for military casualties, both at home and abroad.[3] This paper, in contrast, will examine the effects of the war on the health of the population and services in the acute hospitals, the asylums, the poor law sector and district nursing, offered to the civilian population. Primary sources, for example hospital and nursing association records have been utilised, alongside newspapers, professional journals and the secondary literature, in order to give a broad account of the impact of the war.

Health of the Population

The health of a population directly influences the demands made on its health services. In the UK, during the First World War, the overall mortality rate for the civilian population fell, with the exception of deaths from respiratory diseases. It has been claimed that this general improvement was due to the increases in income and better nutrition for the poorest members of society.[4] This positive view has been disputed with Harris documenting a mixed picture of health gains and deficits for both adults and children across different groups and geographical areas.[5] It would also appear that the overall decline in mortality was a continuation of the long-term trends in the health of the population in the pre-war era.[6] Even so, between 1913 and 1918 the death rate from pulmonary tuberculosis in England and Wales increased by twenty-five percent in the general population and by thirty-five percent in women aged between twenty and twenty-five.[7] This was thought to be associated with factors such as the movement of the population into urban areas for work and a deterioration in housing conditions.[8] Contemporary experts also implicated the effects of food restrictions, especially the reduction of fats in the diet.[9] The trend can be seen most strikingly in the mental asylums where deaths from tuberculosis almost doubled between 1915 and 1919 at 31.9 deaths per thousand of the population as compared with the previous four years (16.5, 1910 to 1914) and the four years after (13.7 between 1920 and 1924).[10] The rationing of food was more severe in the asylums and the death rate from infectious diseases higher.[11] The influenza epidemic at the end of the war made things worse as those with underlying respiratory conditions were more likely to die. High rates of influenza were reported among nursing and medical staff within enclosed communities such as workhouses, asylums, and hospitals, both civilian and military.[12] This put an additional strain on the already hard-pressed hospital services, with district nursing associations taking on extra patients.[13]

Voluntary Hospitals

Voluntary hospitals were charitable institutions dependent upon donations and subscriptions to pay for the treatment of working-class people. They differed in size from the small cottage hospitals in rural areas and typically comprised large general hospitals in the major cities. They concentrated upon treating curable, acute conditions and were major centres for medical and nursing education and training. The war generated two main problems for the voluntary hospitals: a lack of income to match the rising costs of supplies including equipment, food and drugs and secondly a shortage of skilled personnel prompted by the call-up of many doctors and nurses. In the case of Birmingham, the price of drugs at least doubled with the cost of analgesia increasing the most. For instance, aspirin was two shillings and two pence per pound before the war but was twenty-five shillings by 1917. Similarly, the price of cocaine increased from five shillings and six pence to thirty-three shillings per ounce.[14] In response to the shortage, the Women’s Hospital in Birmingham was quite resourceful as it joined a Board of Agriculture initiative to grow medical herbs from seed. The Skin Hospital, in the same city, faced with an acute shortage of imported drugs, mainly from Germany, reinstated medicinal baths. They were said to be out of fashion in 1907 but their use doubled in the first two years of the war.[15] The burden of this work fell upon the nursing staff.

As a result of rising costs, many hospitals made special appeals to increase subscriptions and donations to fund their work. In June 1915, The Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle-upon-Tyne entreated the local public to support its work as it had increased its beds to 578. Of these 200 were reserved for the military, with over 2,300 soldiers treated since the beginning of the war and over 30,000 new recruits inoculated in the outpatient department. Volunteers from the Red Cross and St John’s Ambulance brigade were being trained within the hospital and there were over one thousand people on the waiting list for treatment. The pressure on the staff was said to be intense and the finances were in a parlous state with a deficit of over £12,000.[16] The situation in Newcastle was not an isolated case.[17] Throughout the war, voluntary hospitals had added competition for funds from war hospitals and charitable activities which supported wounded servicemen.

The recruitment of many doctors who were called up for military service put greater strain on the permanent nursing staff of the hospitals who took on extra responsibilities. For instance, the matron and senior sister of the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital in Birmingham took over much of the role of the resident house surgeon during the war.[18] At the Royal Infirmary in Preston, Sister France took over the running of the X-Ray department when both radiologists were called up and her work was seen as invaluable to the running of the hospital.[19] Many matrons and senior staff were thanked publicly in annual reports for their increased efforts in providing the care for civilian patients and in maintaining strict economy in the running of the domestic affairs of their respective institutions.[20] In 1916, the London Hospital as a result of a reduction in staff and finances decided to discharge all outpatients with chronic conditions, such as leg ulcers, and that the staff would only see the number of patients that they could cope with during any one day.[21]

As early as November 1914 the large London hospitals were reporting a shortage of nurses due to military recruitment.[22] Although many nurses who left for war work were replaced by more junior staff, doubts arose about the abilities of some nurses to undertake the work and maintain the quality of care. At the Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, in 1915, the medical staff felt that there was such a deterioration in the quality of the nurses that some of the sisters were incapable of managing the staff and ensuring good patient care. In-experienced staff and probationers were left in sole charge of wards at night and those working in the operating theatres were not specifically trained for the work. Like most other hospitals, The Royal Berkshire tried to recruit more nurses by paying staff more through a war bonus.[23] Recruitment was difficult as army nurses earned more than their civilian counterparts. As soon as many nurses qualified, they joined the Territorial Force Nursing Service or Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service. This appeared more attractive as well as better paid. Virtually all hospitals had to either increase salaries or pay war bonuses to keep staff and attract recruits.

From 1914 onwards hospitals altered their entry requirements for nursing staff. At the General Hospital Birmingham, the age on entry and the physical requirements such as height and weight were relaxed. Before the war probationers were admitted between the ages of 21 and 30; during the war probationers ranged from 17 to 34. This resulted in a doubling of the numbers of probationers during the war as compared to the five years before 1914 (150 as opposed to 72) but virtually all those qualifying during the war years left to take up military appointments. After the war probationers reverted back to normal careers and the majority once again chose the more profitable private nursing over hospital practice. Shortages were to continue into the 1920s. During the war the Queen’s Hospital in Birmingham only avoided a shortage of nurses by recruiting thirty-three special probationers with a reduced period of training in 1915 and by closing its private nursing department (and thus redeploying nurses to the hospital).[24]

The life of a probationer in the voluntary hospitals probably changed very little. Dorothy Moriarty, a first-year probationer at University College Hospital in London stated ‘Looking back, I realise what a very small world was that of a probationer nurse. Outside the red-brick walls of our hospital, across the English Channel, a war was raging. And yet, except when one of our menfolk came home on leave, or a Zeppelin raid robbed us of sleep, or there was the name of someone we knew in the casualty lists, we were smothered in trivia that obscured the larger issues…’[25] For Dorothy, as a probationer, it probably did not matter whether Britain was at war or not or whether she was working in a civil or military hospital. For a probationer the work of a nurse consisted of sheer hard work and long and tiring days of ‘helping with patients, scrubbing lockers, cleaning brasses, washing tiled walls in sluices and bathrooms, and emptying bedpans’.[26] What was happening in the outside world probably did not intervene in the day-to-day routine, described as ‘anything but exciting or romantic – often painfully monotonous’ by one pre-war nurse.[27]

The training and use of Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses (VAD) in the civilian hospitals was controversial and conflict sometimes ensued.[28] Widespread criticism, in the nursing press, of their employment in military and civil hospitals came from those trained nurses who had undertaken a three-year training. This was a sensitive matter much inflamed by Katherine Furse, the national VAD Commandant who objected to the treatment that volunteers had to endure in the hospitals from the trained nursing staff. For her the best professional nurses had gone into the military leaving ‘the dregs’ of the nursing profession behind.[29] This was not the case in most voluntary hospitals. VADs were allowed to train and work in all hospitals but in the case of the Leicester Royal Infirmary the recruitment of volunteer help was restricted, partly to protect the professional nursing staff.[30]

Most civilian hospitals made beds available to the military and were paid by the war office. By the end of the war about one quarter of civilian beds had been requisitioned by the military. Sir Henry Burdett warned about the potential neglect of the civilian population at the beginning of the war.[31] Thus the remaining civilian wards often became overcrowded due to the constant demand and partly as a result of the shortage of private nurses which meant more middle-class patients were admitted to hospitals for care and treatment.[32]

Furthermore, as part of the war effort industrial output of munitions and goods required by the armed forces increased and as a result industrial accidents rose putting greater demand on hospitals. In cities like Birmingham industrial injuries increased dramatically as a result of the increased war work in factories.[33]Thus in 1915, 95% of all casualties seen at the Birmingham Eye Hospital were munition workers.[34]

Mental Health Care

There was widespread industrial unrest in the country in the run up to war in 1914 including action by asylum attendants and nurses protesting about their conditions of employment.[35] The numbers of patients in the public asylums had gradually increased to about 100,000 and by the outbreak of war asylums were said to be ‘too often overcrowded, understaffed, unhygienic and warehouse like’, making the care more likely to be custodial rather than therapeutic.[36] This had deleterious effect on the terms and conditions of the staff, especially as most lived within the asylum. The National Asylum Workers Union (NAWU), founded in 1910, directly challenged the established Asylum Workers Association, which was dominated by senior staff and said to be too close to the asylum managers. The NAWU advocated the use of industrial action to improve conditions for its members and there were several instances of clashes between the union and asylum authorities within the United Kingdom.[37] At the outbreak of war this action ceased but the asylums were faced with a greater challenge. The wave of enthusiasm for the war resulted in many male nurses enlisting in the armed forces, with over one half of the pre-war total having enlisted by 1916. These were replaced by a mixture of the retired, those exempted from military service and female nurses but this resulted in a shortage of skilled and experienced carers for the asylum residents. Although nurses were able to claim exemption from military service under the Military Service Act of 1916, the military authorities aggressively pursued the recruitment of male asylum nurses for active service.[38] The shortage of nurses was also felt in the private mental hospitals with Dr Bedford Pierce, the medical superintendent of the York Retreat, complaining that admissions had been curtailed due to a shortage of nurses. This made it more difficult to admit patients requiring increased and intensive personal attention.[39]

In 1915 the War Office drew up a plan to requisition nine asylums across the country and convert them into military hospitals due to a greater demand for accommodation for wounded combatants. This required the removal and relocating of 12,000 patients. They were sent to asylums as near to home as possible but it did cause problems for visitors and the continuity of care. However, the main problems were due to severe overcrowding in those places that received new patients and in the deterioration in the quantity and quality of food that patients received. By 1918 the annual death rate amongst patients had doubled from ten percent per annum in 1914 to twenty percent in 1918.[40] Most deaths were attributed to infectious diseases particularly tuberculosis, but also dysentery, typhoid and influenza. Tuberculosis within asylums accounted for half of the national total of cases. Death rates did vary between asylums and those that cut the patients food rations the most, tended to have the highest death rates.[41] An examination of the records of the Buckingham Asylum shows that the governing committee cut the food allowance to patients dramatically during the war to keep down costs, and this was followed by a large increase in deaths from tuberculosis which only abated after the diets had been restored to their pre-war levels.[42] In addition, the medical superintendent of the Hanwell Asylum near to London pointed to the lack of ventilation in the wards and the little time spent outdoors by patients as factors in the increase of tuberculosis deaths during the war. A lack of coal to maintain an adequate room temperature and insufficient bed linen prevented the opening of windows within wards[43] Severe staffing shortages due to men joining the armed forces would have no doubt impinged on normal activities such as the supervision of outdoor recreation. As well as this, some of the problems in identifying and preventing disease was put down to the relative inexperience of the new staff.[44]

At the Cornwall Lunatic Asylum, Bodmin, the wards were overcrowded (1226 patients in a hospital that could accommodate 1000). This led to deteriorating working conditions for the staff consisting of an increased workload, longer hours and the cancellation of leave. Sickness amongst staff increased dramatically and several nurses were taken ill with infectious diseases with one dying from diphtheria. The arrival of patients from Bristol in 1915 coincided with a rapid rise of staff with dysentery and diarrhoea. The working conditions and health of the female nurses was particularly affected and by October 1918 had reached such a low point that they joined the NAWU and took industrial action. The union succeeded in obtaining better working conditions and pay. As a result of this action and others like it the asylum nurses quickly unionised.[45] The wartime conditions contributed to the rise of trade unionism within the ranks of nurses in the asylums in the immediate post war period. The new Ministry of Health (MOH) took over the asylums in 1919, changing their title to mental hospitals and that of attendant to nurse. The NAWU succeeded in obtaining concessions from the MOH including a reduction in the working hours to sixty per week and the creation of the Joint Conciliation Committee in which employers and union representatives discussed terms and conditions for nurses.[46] However, militant action increased in the early 1920s during an economic recession, culminating in the ‘Battle of Radcliffe’ where, mainly female nurses barricaded themselves into wards and fought with the police and bailiffs at the Radcliffe asylum in Nottinghamshire in 1922. The strike and sit-in were a result of the proposals to increase the nurses’ working hours and reduce their pay. The strike was broken, the nurses dismissed, and the union nearly went bankrupt.[47] Nevertheless, by the end of the decade the material conditions for nurses was said to have improved.[48]

Poor Law Nursing

For the poor law workhouses and the workhouse infirmaries, life went on much the same at the outbreak of war. Nurses in the sector cared for the physically ill as well as those with mental health issues and learning disabilities. The majority of the sick consisted of the elderly and the chronically ill. The military could not easily requisition wards in workhouses due to the stigma attached to the poor law and also to the mixed nature of the inmates. However, by 1915 the high number of casualties made it a necessity for the poor law authorities to give up some accommodation to the military. As a result, the armed forces took over entire institutions. Workhouse Infirmaries seen to be on a par with those in the voluntary hospitals, possessing modern facilities including operating theatres in places such as Brighton, Birmingham and Reading. By January 1915 the military had taken over 30,000 beds in the poor law sector and by 1918 this had risen to over 56,000 beds.[49] In order to accommodate those displaced by soldiers the poor law authorities sent paupers to neighbouring unions or rented hotels and public buildings such as schools. In some cases, there was widespread opposition against placing patients in certain localities.[50] In Birmingham, where the workhouse Infirmary at Dudley Road was requisitioned, patients were relocated to two other workhouse infirmaries in the city, the main building of the workhouse itself, and workhouses in Kidderminster, Solihull, Stourbridge and Wolverhampton. Patients with tuberculosis were transferred to the city’s isolation hospitals.[51] When the Risbridge workhouse in Suffolk was taken over the inmates were transferred elsewhere but the guardians at Whittlesey stipulated that inmates identified for removal should be ‘neither sick, decrepit nor imbecile’.[52] In some workhouses, as the war progressed, overcrowding became a serious problem. At Grimsby workhouse, in 1916, the children were said to be sleeping three to a bed after the children’s home had been taken over by the military.[53]

In a few workhouses the nurses and other staff were retained by the military authorities on their poor law salaries and conditions. This led to some problems, especially in Birmingham where the military authorities proposed to pay the VAD trainee nurses more than the infirmary’s ordinary probationers.[54] Just as in the voluntary hospitals and asylums staff shortages began to show, with qualified nurses taking up military posts. In Croydon the workhouse nurses felt they were under pressure to volunteer as they had been labelled ‘slackers’ by those who had already signed up.[55] Elsewhere shortages of nurses began to tell on the ability of poor law unions to care for patients. The superintendent nurse at the Southampton Poor Law Infirmary reported that there were fifty-two sisters and probationers in January 1915 when there was a need for seventy-five.[56] Guardians at Nantwich in Cheshire, hearing of the resignation of the charge nurse and the refusal of an interviewee to take up the post because the hospital was not up to date, asked whether they could revert to the outlawed system of the untrained matron supervising the nursing of patients.[57] In Leeds the guardians reported the workhouse hospital was almost denuded of nurses and that they were using inmates to nurse, a practice banned since 1897, and employing more probationers in the place of the qualified.[58] Similarly, the guardians in Walsall who were unable to replace a charge nurse who had resigned decided to fill the vacancy with additional probationers.[59] The Thetford workhouse in Norfolk, in 1916, had one head nurse and two assistants to care for 144 patients every night throughout the year.[60]By 1918 the shortage of nurses prevented new accommodation for tuberculosis patients in Liverpool being brought into use.[61] The situation was seen as so serious in 1915 that the Workhouse Nursing Association put forward a resolution to the annual conference of the National Union of Women Workers to call upon the Local Government Board to create a national nursing service to deal with the problem. Further resolutions were submitted in the following two years but the Board did not act upon the suggestion.[62] Criticism of the situation focussed on the failure of the poor law authorities to improve conditions and salaries of nurses in order to match that obtainable in military hospitals.[63] In the end just like the voluntary hospitals the guardians of the poor had to provide better salaries and war bonuses to retain or recruit staff.

In order to save resources local boards of guardians started to look at expenses and in particular at the cost of food in workhouses and the Atcham board in Shropshire looked to reduce the rations of its inmates. The Poor Law Officers Journal commented ‘there should be no war economy at the expense of “other” people’s stomachs, and certainly not at the expense of the chargeable poor’[64] However, in early 1917 the President of the Local Government Board suggested that workhouses should implement the government Food Controller’s recommendations for adult food consumption by reducing the amount of bread and meat consumed by inmates and staff. Surprisingly, the changes were said to be more nutritious and more varied than the previous dietary offered by several boards of guardians.[65] However, near to the end of the war, the guardians of the poor at Todmorden decided to petition the Local Government Board to increase the bread ration for the inmates of the workhouse, as the national guideline ‘was insufficient for maintaining the inmates in a satisfactory state of health’.[66] Overall, the rapidly-worsening conditions for patients in the mental asylums do not seem to have been duplicated in the poor law sector. In spite of the fact that the military requisitioned large numbers of poor law buildings the numbers of workhouse inmates actually fell between 1914 and 1919.[67] The numbers of sick residents remained constant during the war but, unlike the asylums, there was no national record keeping regarding morbidity or mortality rates to compare the periods before, during and after the war (and therefore we are lacking suitable data for comparison).

District Nursing

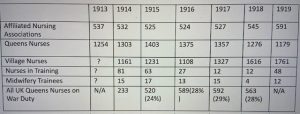

District nursing associations, first founded in the 1860s to care for the sick-poor in their own homes and funded by charity, were widespread across the country by 1914. Some associations were independent organisations employing nurses, with varying levels of qualification and experience, who were deemed suitable to nurse the poor in their own homes. Others were affiliated to the Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Institute for Nurses which controlled the training and inspection of district nursing for these associations across the UK. The Institute trained two types of nurses: Queens Nurses who had undergone a three year’s training in an approved hospital school and six months training in district nursing, and Village Nurses for rural areas who had a minimum of one year’s experience in hospital nursing and further training in midwifery and district nursing. The latter were under the supervision of the county associations whilst Queens Nurses tended to work in urban areas, directly employed by local associations. District nursing, just like that in the hospitals, depended upon recruiting good quality staff. By the end of 1914, 233 Queen’s Nurses had left to join the military and throughout the war over one quarter of the entire UK Queen’s Nursing workforce was doing war work. This put a great strain on local associations in their attempt to maintain the service and the Institute started to offer training to women who did not meet the strict criteria that were applied before the war. This was essentially an elitist organization which only accepted nurses who had had a three-year training in an approved hospital with a resident medical officer and who came from ‘respectable’ backgrounds. By the middle of 1915 the Institute decided to accept nurses with two-year’s training; accepted a nurse from Southend Hospital which was not an approved training school; and allowed a nurse from Gloucester who had previously been in domestic service to train as a district nurse. The executive committee of the institute maintained that none of these breaches of the rules would form a precedent in a post-war future and it drew the line in accepting a nurse who had been trained in a poor law hospital because it did not have a recognised training school.[68] In spite of this flexibility, recruitment was severely reduced. In reply to the war office asking about the supply of more nurses to the military, the executive committee thought that associations should make the decision but it considered that village nurses ‘would be more valuable working as midwives in their districts than as assistant nurses in War Hospitals’.[69]

The fees for training nurses were paid for by the national executive committee and as a result of a decrease in applications it cut its grant to training homes across the country. This resulted in financial hardship, as local associations had to recruit qualified district nurses to replace the trainees. Smaller district nursing associations in London and suburban Birmingham decided to charge patients six pence per visit in order to fund the increased costs of the service.[70] All costs spiralled during the war and most associations gave in to pressure to increase the nurses’ salaries or give war bonuses to retain staff.

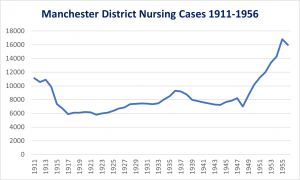

In both Birmingham and Manchester, the war seriously affected the respective organisations required to deliver care. In both cities nurses were recruited to the military and were not replaced. In Manchester the number of cases that were visited plummeted during the war and it took until the 1950s for the number of cases to reach the same level as before World War One (See Figure 1).[71] In late 1914 the Birmingham District Nursing Society was finding it difficult to fill vacancies and by 1919 in one district there were nine vacancies out of 16 posts. During the war, in order to cope the Society accepted nurses not qualified in district nursing and also reinstated married women who had given up nursing before the war. In addition it supplemented trained nurses with volunteers from the St John Ambulance Brigade and in 1916 in the Summerhill district, where there were only two qualified district nurses and five unqualified, the Brigade made nearly 9,000 visits to the elderly and chronic cases.[72] The Lady Superintendent recruited nurses from Holland, and at least one Dutch nurse was taken on for training, but the Queens Institute ruled in September 1916 that only British subjects could be enrolled as trainees and this source of nurses stopped. The Society kept up its other commitments as it had a contract with the Birmingham Small Arms Company to provide factory nurses and took on another with The Electric & Ordnance Accessories Company also in Birmingham. At the latter in the first three weeks of work the nurses applied nearly three and a half thousand dressings.[73] In September 1916 the Ministry of Munitions took over the entire female workforce in factories, including the nurses, and this valuable source of income to the Society ceased.

Figure 1. Manchester District Nursing Cases 1911-1956.

Source: Manchester Archives & Local Studies: Manchester Nurse Training Institution Annual Reports, 1866 – 1954 (362.1 M85)

District nursing organisations in large cities remained under considerable pressure for many years, especially as their income as charities was severely interrupted during the war and did not recover until sometime afterwards. The Birmingham Society faced particular problems in the immediate post war period, complaining that the shortage of nurses and rising costs due to increased salaries, improved off duty time, and longer holidays put it under undue financial pressure. By October 1920 it had closed one of its three nursing homes in order to contain spending, albeit at some cost to its patients.[74] During the war, district nursing managed to carry on and afterwards the Queen’s Institute recovered, both by increasing the numbers of affiliated associations and eventually succeeded in returning training back towards its pre-war levels (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Annual Statistics of the QVJNI for England 1913 – 1919.

Source: WL QVJNI Annual Reports 1914-19 (SA/QNI/B.12 -16)

Aftermath

The war had caused great stress to the population. The concentration on the care and treatment of military casualties deprived the civilian services of resources and personnel. In terms of the ratio of nurses to patients throughout the war, the needs of military officers came before the needs of other ranks and the needs of the armed forces before the needs of the civilian sick. Relatively minor conditions afflicting the military came before the care needs of women, children, old people, the mentally ill and those with tuberculosis.[75] Prolonged conflict had dire consequences for many patients with the most vulnerable in society paying a heavy price for Britain’s involvement in war. In contrast, the nursing profession gained much from its participation in the conflict.

At the end of the war, the president of the Leicester Royal Infirmary Nurses’ League, an association of those nurses who had trained or worked in the hospital, wrote

High tributes have been paid to the work of Nurses during the war, honours have been showered upon them. Never, I suppose, in all its history has the Nursing profession held such a high place as it holds to-day.[76]

Nurses were amongst the many women who had contributed to the war effort and this was identified by politicians as one of the reasons to widen the franchise to some women in 1918. Such was the reputation and standing of nursing that a year later the Nurses’ Registration Act was passed by the British Parliament giving the trained nurse legal and professional status. Prior to this, an almost thirty-year campaign to bring about registration had failed to make any impact on successive governments.[77] Legislation heralded a new era for nursing, which would, eventually impose minimum standards for education on all branches of the profession and pave the way for better terms and conditions.

However, all was not well in the caring profession as the war had profound effects, with acute shortages of nurses in all branches extending into the 1920s. This was accompanied by widespread criticism of nurses’ terms and conditions of employment but only mental health nurses took direct action to protest and improve their situation (see section above). During the war the National Union of Trained Nurses put forward reasons for the nation-wide shortage of general nurses. Nurses, it stated, had a hard life consisting of long hours and constant physical and mental strain, coupled with poor food and a lack of comfortable accommodation. Moreover, by the time they had completed their training, many were almost thirty years of age and probably only had about twenty years to be able to work and accumulate enough money for their retirement before physical infirmity caught up with them. This, the union concluded, was a disincentive to women, especially the educated, to enter the profession and calls for reform became more vociferous.[78]The shortage of nurses was a persistent problem. In 1919 the General infirmary in Leeds could not open its new extension fully because of poor nurse recruitment.[79] Private nursing was also affected with the Staffordshire Nursing Institute having to refuse over 200 cases because of a lack of nurses. The staff numbered just 67 in 1920 as opposed to 156 in 1910.[80] Acute problems in recruitment to workhouses, especially rural ones, was acknowledged by the new Ministry of Health.[81] Shortages were a result of both the unappealing nature of the work and the alternative careers opening up for women; for example, a career as a masseuse (physiotherapist today) took half the time to train and offered more than twice the salary of hospital nurses. In addition some nurses could find alternative paid employment in school nursing and health visiting which offered better hours and conditions of employment and an alternative to living in hospital accommodation.[82]

In the post-war period, the Ministry of Health took over responsibility for the poor law sector and encouraged local boards of guardians to improve the terms and conditions for staff. This resulted in many unions reducing nurses’ duty time towards a 48-hour week and improving their salaries.[83] Objections to reducing hours of work came from the voluntary hospitals who balked at the possible increased costs in recruiting more nurses to make up for the shortfall in hours. The College of Nursing which was controlled by elite matrons and senior nurses in the voluntary hospitals resisted the reduction in hours throughout the 1920s.[84] They fell back on a system that, in essence, was devised to meet the challenges of the workforce in the 1860s and to keep costs down.[85] This system could not last as it prevented innovation in practice and education.[86] The newly created General Nursing Council’s requirements for training nurses went some way to improving the conditions for probationers or students as they were soon to be called. Measures such as lowering the age of entry to training, better facilities for teaching and learning, and the improvement of living accommodation for nurses were much easier to implement across the entire health sector. This together with better salaries, hours of work and holidays did much to improve the lives of nurses.

Overall nursing as an occupation emerged with credit for what it did both in military and civilian practice in the First World War. The civilian services were affected by acute shortages of nurses and the increased costs of equipment, food and other resources. Patients and nurses in the mental hospitals suffered the most. However, most civilian nurses were hardly touched by the horrors that were occurring across the channel except in that some experienced the occasional air raid and perhaps treated the civilian wounded. For most, blackouts were the greatest inconvenience entailing, for district nurses, the rescheduling of visits from the evening to the afternoon to avoid dark streets. The war acted as a catalyst to change and improve the lives of nurses and it ushered in a new era of professional practice under a new government ministry and the General Nursing Council.

Endnotes

[1] William McPherson History of the Great War: Medical Services General History, Volume 1 Medical Services in the United Kingdom etc., (London: HMSO, 1923), 106.

[2] See for example: Christine Hallett, Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009); Susan McGann, Anne Crowther & Rona Dougall, A History of the Royal College of Nursing, 1916-90, (Manchester, Manchester University Press: 2009); Christine Hallet, ‘“Emotional nursing” Involvement, and Detachment in the Writings of First World War Nurses and VADs’ in Alison Fell and Christine Hallett (eds), First World War Nursing: New Perspectives, (New York: Routledge, 2013), 87-102; Yvonne McEwen, In the Company of Nurses: the History of the British Army Nursing Service in the Great War, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014).

[3] Stuart Wildman, ‘Nursing on the Home Front: Britain, 1914-1919’ The Bulletin (UK Association for the History of Nursing), 4 (2015), 32-43.

[4] Jay Winter, The Great War and the British People, (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1986)

[5] Bernard Harris, The Origins of the British Welfare State: social welfare in England and Wales, 1800-1945. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 167-170.

[6] Michael Daunton, Wealth and Welfare: An Economic and Social history of Britain, 1851-1951. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 365.

[7] Linda Bryder, ‘The First World War: Healthy or Hungry?’ History Workshop Journal, 24/1 (1987), 141-157.

[8] Arthur Newsholme, ‘The Relations of Tuberculosis to War Conditions’ The Lancet, 20 October 1917, 591; James Crichton-Browne, ‘Tuberculosis and War’ The Journal of State Medicine, 25/5 (1917), 144-146.

[9] Frank Elkins and H. Hyslop Thomson, ‘The Incidence of Tuberculosis Amongst Asylum Patients’ The Lancet, 9 August 1919, 242-244; Bryder, ‘The First World War’, 146-148.

[10] Bryder, ‘The First World War, 147.

[11] Linda Bryder, Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1988), 108-109.

[12] Niall Johnson, Britain and the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic: A Dark Epilogue (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), 109-110.

[13] For instance, the Westminster Nursing Committee, London reported an increase of 30% in cases due to the influenza outbreak: Wellcome Library (WL), SA/QNI/X65/30 Westminster Nursing Committee Annual Report 1918, 5. A similar rise in cases was documented at the nearby Chelsea, Pimlico and Belgravia association: WL, SA/QNI/X.16/2 Chelsea, Pimlico and Belgravia Nursing Association, Annual Report, 1919, 8.

[14] Anonymous, ‘Work of Birmingham Hospitals’, Birmingham Daily Post, 22 March 1917, 3.

[15] Jonathon Reinarz, Health Care in Birmingham: The Birmingham Teaching Hospitals 1779-1939, (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009), 145 and 156.

[16] Anonymous, ‘The Royal Infirmary: An Appeal for New Subscribers’ Newcastle Journal, 17 June 1915, 7.

[17] See for instance Anonymous, ‘Coventry Hospital Appeal’ Coventry Herald, 5 February 1915, 6; Anonymous, ‘Royal Berkshire Hospital Appeal Fund’ Berkshire Chronicle, 19 October 1917, 5; Anonymous, ‘Manchester Eye Hospital, Appeal for Funds’ Manchester Evening News, 30 January 1918, 2.

[18] Birmingham Archives and Heritage (BAH) HC/RO/A/15 Royal Orthopaedic Hospital, Birmingham Annual Report, 1916, 27.

[19] John Wilkinson, Preston’s Royal infirmary, (Preston: Carnegie Press, 1987), 80-1.

[20] BAH HC/WH/1/10/5 Women’s Hospital Birmingham Annual Report, 1916, 27. ; BAH L46.316 76549 Birmingham Skin and Urinary Hospital, Annual Report, 1917, 16. ; Robert Bewick, The History of a Provincial Hospital: Burton upon Trent (Burton upon Trent: David Whitehead Ltd, 1974), 83-89.

[21] Poor Law Officers Journal, 11 August 1916, 1277.

[22] Anonymous, ‘Shortage of Nurses’ Nursing Times, 28 November 1914, 1481.

[23] Margaret Railton and Marshall Barr, The Royal Berkshire Hospital, 1839-1989, (Reading: Royal Berkshire Hospital, 1989),173.

[24] Katherine Tucker, The Effect of the First World War on the Organisation and Provision of Nursing Services in Birmingham(unpublished Bachelor of Nursing Dissertation, University of Birmingham, 2004), 40-51.

[25] Dorothy Moriarty Dorothy: the memoirs of a nurse 1889-1989, (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1989), 95.

[26] Christopher Maggs, The origins of general nursing. (London, Croom Helm, 1983) 107.

[27] Mary Gardner, ‘Nurses in modern fiction’ The Nursing Record & Hospital World, 7 April 1900, 279.

[28] Robert Dingwall, Anne Marie Rafferty and Charles Webster, An Introduction to the Social History of Nursing (London: Routledge, 1988), 72-75.

[29] Janet Watson, ‘Wars in the Wards: The Social Construction of Medical Work in First World War Britain’, The Journal of British Studies, 41/4 (2002), 507.

[30] Earnest Frizelle and Janet Martin, The Leicester Royal Infirmary, 1771-1971, (Leicester: Leicester No1 Management Committee, 1971), 191.

[31] Anonymous, ‘The Hospital Necessities of the Civilian Population’ The Hospital, 22 August 1914, 561-2.

[32] Harris, The Origins of the British Welfare State, 174.

[33] BAH HC GH 1/3/24 Birmingham General Hospital, Annual Reports, 1913 – 1917.

[34] BAH L46.314 224029 Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital Annual Report 1915, vi-vii.

[35] The terms attendant and nurse are used interchangeably in some sources. In 1920 the Ministry of Health indicated they were to be called nurses. This paper will use the term nurse to refer to the care staff who worked directly with patients.

[36] Claire Hilton, Civilian Lunatic Asylums During the First World War: A Study of Austerity on London’s Fringe (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 265.

[37] Niall McCrae and Peter Nolan The Story of Nursing in British Mental Hospitals: Echoes from the Corridors. (London: Routledge, 2017), 62-63; Barbara Douglas, ‘Discourses of Dispute: Narratives of Asylum Nurses and Attendants, 1910-22’, in Anne Borsay and Pamela Dale (eds), Mental Health Nursing: The Working Lives of Paid Carers in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), 101- 103.

[38] Peter Nolan ‘The York Retreat During the First World War – a Case Study’ The Bulletin (UK Association for the History of Nursing), 6 (2017), 28-43.

[39] Anonymous, ‘The York Retreat’ Nursing Times, 2 February 1918, 147.

[40] John Crammer ‘Extraordinary Deaths of Asylum Patients During the 1914-1918 War’ Medical History, 36/4 (1992), 430.

[41] Claire Chatterton, ‘Inpatient mental health care in the First World War’, Mental Health Practice, 19/1 (2014), 35-37.

[42] Crammer, ‘Extraordinary Deaths’, 435

[43] Hilton, Civilian Lunatic Asylums, 226.

[44] Chatterton, ‘Inpatient mental health care’, 37.

[45] Debbie Palmer, Who cared for the carers? A history of the occupational health of nurses, 1880-1948. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 50-60.

[46] McCrae and Nolan The Story of Nursing in British Mental Hospitals, 65-67.

[47] Rosemary Collins, ‘1922 Nurses Strike at Nottinghamshire County Mental Hospital’ The Bulletin (UK Association for the History of Nursing), 11 (2023).

[48] McCrae and Nolan The Story of Nursing in British Mental Hospitals, 73.

[49] Local Government Board, Forty-Seventh Annual Report of the Local Government Board, 1917-18, Command Paper 9157, (London: HMSO, 1918), 46.

[50] Brian Abel-Smith, The Hospitals, 1800-1948, (London: Heinemann, 1964), 261.

[51] Poor Law Officers Journal, 23 April 1915, 490.

[52] Poor Law Officers Journal, 26 February 1915, 257.

[53] Anonymous, ‘Grimsby Board of Guardians’ Grimsby News, 24 March 1916, 2.

[54] Poor Law Officers Journal, 26 November 1915, 1365-6.

[55] Poor Law Officers Journal, 19 November 1915, 1301.

[56] Poor Law Officers Journal, 22 January 1915, 102.

[57] Anonymous, ‘Staffing of Nantwich Infirmary’ Nantwich Guardian, 19 February 1915, 3.

[58] Anonymous, ‘Shortage of Trained Nurses in Leeds’, Yorkshire Evening Post, 24 September 1915, 5.

[59] Anonymous, ‘The Shortage of Nurses’, Birmingham Daily Post, 30 September 1916, 4.

[60] Anonymous, ‘Norfolk in World War 1’, Wellcome History, 54 (2014), 8.

[61] Anonymous, Shortage of Nurses Liverpool Daily Post, 6 September 1918, 4.

[62] Anonymous, ‘National Union of Women Workers and Nursing’, British Journal of Nursing, 21 August 1915, 161; Anonymous, ‘National Union of Women Workers’ British Journal of Nursing, 14 October 1916, 161; Anonymous, ‘National Council of Women’ Nursing Times, 22 September 1917, 1132.

[63] Anonymous, ‘Shortage of Nurses’, Nursing Times, 11 September 1915, 1098; Anonymous, ‘Shortage of Poor Law Nurses’ Nursing Times, 18 September 1915, 1148.

[64] Poor Law Officers Journal, 5 January 1917, 1298.

[65] Anonymous, ‘Cambridge Guardians’ Cambridge Daily News, 3 May 1917, 4; Anonymous, ‘Workhouse Rations: Tunbridge Wells’ Sussex Daily News, 15 May 1917, 4; Anonymous, ‘Workhouse Rations’ Western Evening Herald, 25 October 1917, 3.

[66] Anonymous, ‘Todmorden Board of Guardians’ Todmorden & District News, 23 August 1918, 1.

[67] Ministry of Health, First Annual Report of the Ministry of Health 1919-1920, Command Paper 932, (London: HMSO, 1920), 137.

[68] WL SA/QNI/C.3/10 Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Institute for Nurses, minutes of Council and Committees 1915.

[69] WL SA/QNI/C.3/11 Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Institute for Nurses, minutes of Council and Committees 1916.

[70] WL SA/QNI/X.16/2 Chelsea, Pimlico and Belgravia Nursing Association Annual Report 1918 ; BAH, MS 807 Kings Heath District Nursing Association: Minute Book 6 June 1916.

[71] Stuart Wildman, ‘“The Greatest Human Touch”: District Nursing in Manchester and Salford, 1864 – 1958’, The Bulletin (UK Association for the History of Nursing), 5 (2016), 6-18.

[72] BAH, L46.6 Birmingham District Nursing Society, Annual Reports 1914-1920.

[73] BAH MS 807 Birmingham District Nursing Association: Central Home House Committee Minutes, 13 October 1915.

[74] Anonymous, , ‘Birmingham Nursing Society’ Birmingham Evening Mail, 6 October 1920, 4.

[75] Abel-Smith, The Hospitals, 283.

[76] Records Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, DE7043/62/17 Leicester Nurses’ League Journal, 1918, 6.

[77] Anne Marie Rafferty, The Politics of Nursing Knowledge (London, Routledge, 1996), 43.

[78] Anonymous, ‘Salaries’, Nursing Times, 23 December 1916, 1545; Anonymous, ‘The Revolution’ Nursing Times, 20 July 1917, 753.

[79] Anonymous, ‘Nursing Echoes’, British Journal of Nursing, 21 June 1919, 421.

[80] Anonymous, ‘Staffordshire Nursing Institute’, Staffordshire Sentinel, 23 March 1921, 4.

[81] Ministry of Health, First Annual Report, 35.

[82] Anonymous, ‘Nursing Echoes’, British Journal of Nursing, 21 August 1920, 102.

[83] Ministry of Health, First Annual Report, 35-37.

[84] McGann et al, A History of the Royal College of Nursing, 58-60

[85] Carol Helmstadter, ‘Building a New Nursing Service: Respectability and Efficiency in Victorian England’ Albion, 35/4 (2003), 594-595; Carol Helmstadter, ‘Old Nurses and New: Nursing in the London Teaching Hospitals Before and After the Mid-Nineteenth-Century Reforms’, Nursing History Review 1 (1993), 64-65.

[86] Monica Baly, Florence Nightingale and the Nursing Legacy (London: Whurr, 1997), 219.